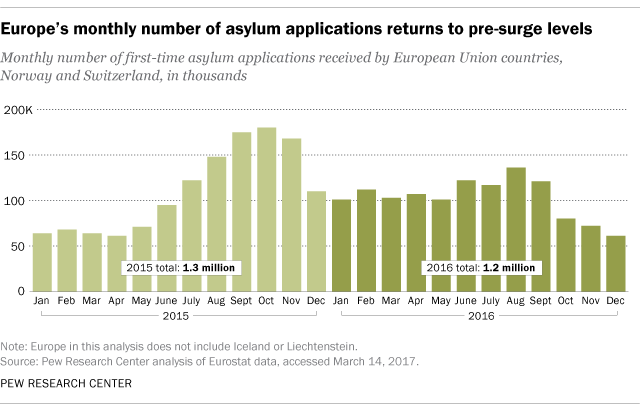

Europe’s record for annual asylum applications was nearly broken last year, but the numbers trailed off considerably by the end of 2016 and fell short of the previous year’s peak surge in late summer and early fall.

In 2016, European Union countries, Norway and Switzerland received more than 1.2 million asylum applications, only about 92,000 fewer than the record 1.3 million applications received in 2015, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of recently released data from Eurostat, Europe’s statistical agency.

At the same time, however, the number of monthly asylum applications in Europe decreased considerably at the end of 2016, dropping from 100,000 or more applications per month for most of 2016 to about 80,000 in October, 72,000 in November and 61,000 in December. The monthly number of asylum applications at the end of 2016 was similar to that of the beginning part of 2015, before the refugee surge.

That 2015 surge began in the spring, when tens of thousands of migrants – most from the Middle East – entered the Continent each month. Consequently, monthly asylum applications increased for six straight months, rising to a peak of 180,000 in October 2015. For most of 2016 (through September), the number of applications dropped to a monthly average of 113,000.

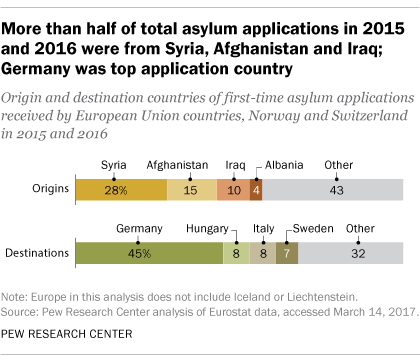

In all, Europe received some 2.5 million first-time asylum applications in 2015 and 2016. The European country with the most applications in the past two years has been Germany, which received nearly half (45%) of these applications, followed by Hungary (8%), Italy (8%) and Sweden (7%). Both Italy and Greece continue to receive new arrivals on their shores, but Italy received more than Greece in 2016.

Among those who applied for asylum in 2015 and 2016, more than half (53%) were nationals from just three countries: Syria (28%), Afghanistan (15%) and Iraq (10%). Asylum applicants from Albania, Pakistan, Nigeria and Kosovo were between 3% and 4% each of all asylum applications.

In Europe, all asylum seekers, whether children or adults, must file applications. They then wait for their case to be reviewed by the country where they filed their application. With a mounting backlog of more than a million applications currently under review by European authorities, decisions can take months or sometimes more than a year. Meanwhile, many asylum seekers wait in government-run facilities where they are provided medical care and food. If an asylum seeker’s application is accepted, they receive permanent residence and permission to work. If their application is rejected, they can file an appeal within a certain period of time, depending on the European country. They are also subject to deportation.

The monthly count of new asylum applications remained around 100,000 for most of 2016, even though the number of new refugees entering the EU via Greece dropped sharply after a March 2016 agreement that saw the EU and Turkey take measures to deter migration across the Eastern Mediterranean.

There are several possible reasons for the absence of a corresponding decrease in new asylum applications with the decline in refugee flows. The first is a lag between the times when refugees arrived in Europe and when they applied for asylum. The German Interior Ministry, for example, states that many asylum seekers who arrived in Germany during 2015 did not file for asylum until 2016.

It is also possible that asylum seekers applied in multiple countries, raising the total number of applications across Europe. Human traffickers, for example, have been very active in smuggling asylum seekers from Hungary to Germany, many of whom first filed for asylum in Hungary. In fact, Eurostat reports that 148,000 asylum applications first submitted in Hungary have been withdrawn since the beginning of 2015, accounting for nearly three-fourths (73%) of all applications received there during the past two years. (Applications can be withdrawn implicitly by an applicant’s not appearing for scheduled meetings, or explicitly by an applicant’s requesting their application be removed.)