With the Republican-controlled House, the Democratic-run Senate and President Obama headed for a showdown — yes, another one — over raising the federal debt ceiling, it’s perhaps helpful to remember that the statutory limit on government debt has been a bipartisan headache for decades.

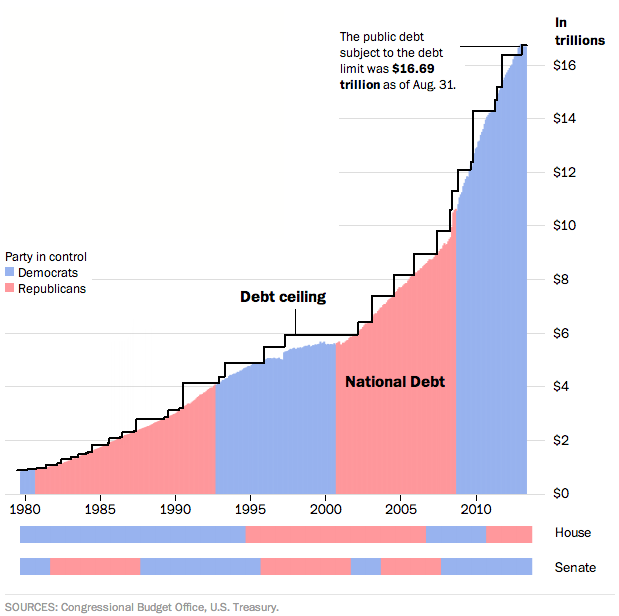

Since 1980, according to this interactive graphic from The Washington Post, the debt limit has been increased 42 times, under both Republican and Democratic presidents and every possible configuration of partisan control in Congress. The limit now stands at $16.699 trillion, up from $1.39 trillion three decades ago; Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew has said the government will hit that limit by Oct. 17.

For nearly 130 years the U.S. got along without an overall limit on government debt; instead, Congress authorized specific debt issuances for particular purposes, such as building the Panama Canal (1902). One such law, the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917, originally authorized borrowing to cover the expenses of fighting World War I, but by 1939 it had evolved into a $45 billion aggregate limit on virtually all federal debt. That law, as amended, became the basis for the current statutory limit. (The Congressional Research Service has prepared a very helpful primer on how the debt limit works and its history.)

Raising the debt ceiling has long been treated as a distasteful chore, the Capitol Hill equivalent of cleaning the gutters. For many years the bills were drafted as temporary increases to a relatively small amount of “permanent” borrowing authority, which led to repeated crises in the 1970s when the “temporary” authorizations expired. As often as not, the debt-limit bills lacked official sponsors, no one apparently wanting to take even nominal responsibility for raising the ceiling.

But the debt-limit disputes, like budget matters generally, have grown more rancorous and sharply partisan over the past few decades, and their solutions have become more and more convoluted. The standoff in the summer of 2011, for instance, was resolved by Congress allowing President Obama to raise the debt limit on his own authority in three stages, the last two subject to congressional vetoes. In February of this year, Congress voted to suspend the debt limit entirely for three and a half months, then retroactively raise it to cover whatever borrowing took place over that span. That’s the $16.699 trillion limit in place today.