Obesity affects roughly 42% of U.S. adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And about two-thirds of Americans (65%) say willpower alone usually isn’t enough for most people who are trying to lose weight and keep it off, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

Put those two facts together, and it should come as no surprise that a new class of drugs to help people lose weight – including Ozempic, Wegovy and similar medications – has soared in popularity. In the Center survey, about three-quarters of Americans say they have heard or read at least a little about these drugs.

This post analyzes obesity rates and uptake of weight-loss drugs in the United States and worldwide. It uses data from Pew Research Center’s recent report “How Americans View Weight-Loss Drugs and their Potential Impact on Obesity in the U.S.” and other sources.

Data on the prevalence of U.S. adults classified as obese and overweight was obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a project of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The NHANES is normally conducted every two years. Some of our findings come from this most recent dataset, and others are from the 2017-18 NHANES. Data from the 2021-23 survey is not yet available.

Global obesity rates for adults were obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO). The most recent estimates are from 2016. To estimate the number of people worldwide with obesity, we also used 2016 population data for adult men and women from each country from the World Bank. We applied WHO’s gender-specific obesity rates to those population estimates, then totaled them to arrive at a global obesity estimate.

Data on the number of prescriptions for and patients using weight-loss drugs came from ClinCalc.com, an online resource for physicians and other health care practitioners. ClinCalc aggregates data from the Prescribed Medicines File (PMED) of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, a project of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

We also analyzed recent financial statements from Novo Nordisk, producer of Ozempic and other semaglutide drugs, and Eli Lilly, maker of Mounjaro and Zepbound. We obtained the companies’ financials via the Securities and Exchange Commission’s EDGAR database of corporate filings.

In the case of Novo Nordisk, which as a Danish company reports its financials in Danish kroner rather than U.S. dollars, we converted its reported revenues to dollars at the rate of 1 krone = $0.145, the prevailing exchange rate when we did the analysis.

Obesity patterns in the U.S. and abroad

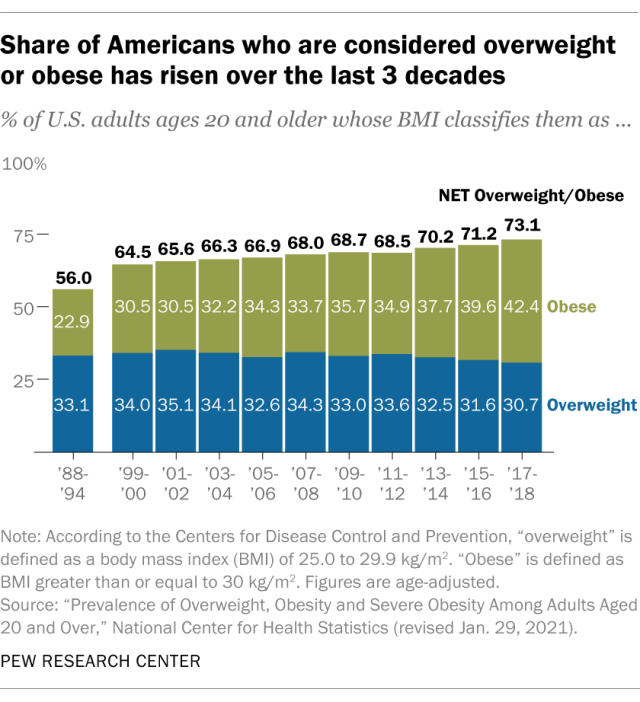

Over the past three decades, the share of Americans categorized as obese (based on body mass index, or BMI, data from the CDC) has risen considerably.

In 2017-18 – the timespan with the most recent data available – about three-quarters of U.S. adults ages 20 and older were considered either overweight (31%) or obese (42%). Just over 9% of adults were considered severely obese. (Note that the CDC survey period spans two years.) About three decades earlier, by comparison, 56% of Americans ages 20 and older were considered overweight or obese, including 3% who were considered severely obese.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the CDC’s data collection, which is why the most recent figures are from 2017-18. However, there’s some evidence from other federal agencies that adult obesity rates rose even higher during the pandemic.

The CDC classifies someone as “overweight” if they have a BMI of 25.0 to 29.9, and “obese” if they have a BMI of 30.0 or greater. People whose BMI is 40.0 or greater are sometimes categorized as “severely obese.” The CDC has more information about BMI, its uses and how to calculate it.

While clinicians and researchers use BMI as a population-level metric and as an individual screening tool to identify potential weight problems, many now advise that BMI alone is an incomplete measure of health. In 2023, for instance, the American Medical Association (AMA) urged doctors to consider additional factors when assessing obesity and health risks, such as body composition, waist circumference and genetic factors. The AMA also noted that health risks differ both between and within demographic groups, and that BMI cutoffs were “based primarily on data collected from previous generations of non-Hispanic White populations and [do] not consider a person’s gender or ethnicity.”

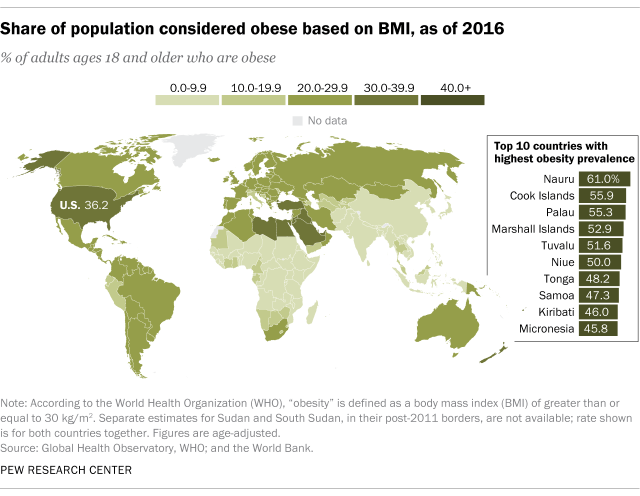

The United States had one of the highest adult obesity rates in the world as of 2016, the most recent year for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has comprehensive data. That year, the U.S. ranked 12th among 191 countries. (Note that the WHO defines adults as those 18 and older, so its figures aren’t directly comparable with the CDC data.)

Worldwide, obesity affected about 663 million adults, or 13% of the global adult population, in 2016. Global obesity rates were 15% for women and 11% for men, based on Center estimates of WHO and World Bank data.

Demand for weight-loss drugs

Americans have only modest expectations that the new weight-loss drugs – formally known as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists – will reduce obesity in the U.S., according to the Center’s new survey. Still, these drugs have taken off in popularity in America, as well as around the world.

Since its 2017 approval as a diabetes treatment, semaglutide (the generic name for Ozempic and its offshoots, Rybelsus and Wegovy) has become one of the most popular prescription drugs in the U.S. It ranked 90th in 2021, the most recent year for which federal data on hundreds of the most commonly prescribed drugs is available. That year, an estimated 8.2 million prescriptions for it were written in the U.S., more than quadruple the number just two years earlier.

Almost 2 million people in the U.S. were taking semaglutide medications in 2021 – more than three times as many as in 2019. (The number of prescriptions exceeds the number of patients because prescription refills and renewals are counted separately.)

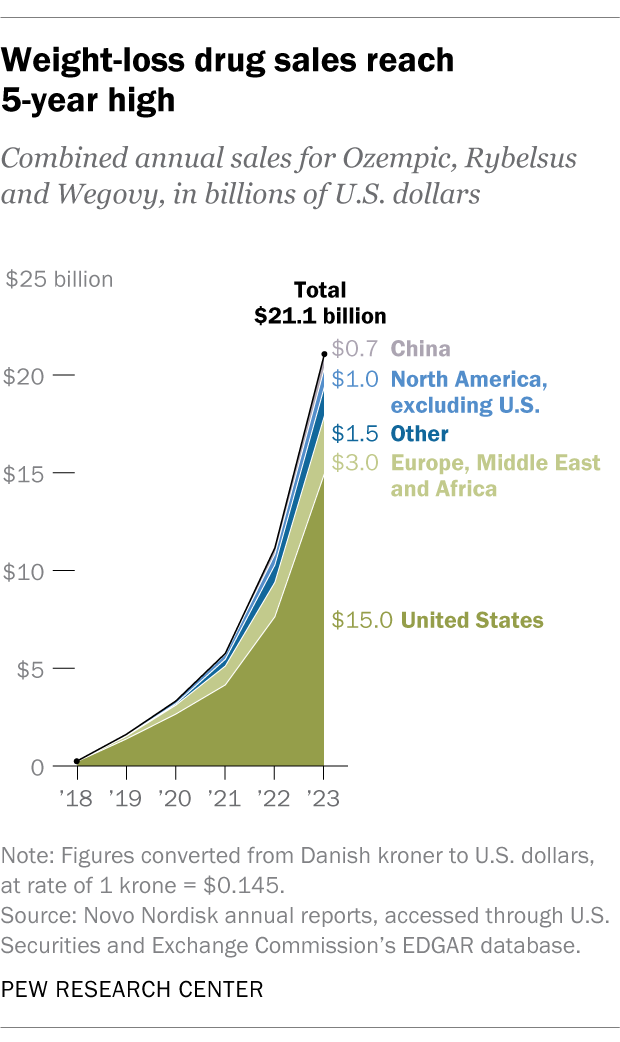

Another indication of weight-loss drugs’ rapid uptake globally comes from the financial statements of their manufacturers. Last year, Ozempic, Rybelsus and Wegovy had combined sales of about $21.1 billion for Novo Nordisk, the Danish company that produces them. That made up nearly two-thirds of Novo Nordisk’s entire revenue that year. The drugs’ combined sales were 89% higher than in 2022. Last year, 71% of semaglutide revenues came from the U.S.

Mounjaro, a similar diabetes drug produced by Eli Lilly with the active ingredient tirzepatide, launched in mid-2022. By the end of 2022, Mounjaro had sales of $482.5 million. In 2023, its first full year on the market, Mounjaro brought in nearly $5.2 billion. In November 2023, the Food and Drug Administration approved a version for weight loss under the name Zepbound.