Widespread dissatisfaction with the role of money in American politics is one of the many themes in Pew Research Center’s recent report on Americans’ dismal views of the nation’s political landscape.

This analysis summarizes key findings about money and politics from the recent Pew Research Center report “Americans’ Dismal Views of the Nation’s Politics.” We conducted the study to better understand how Americans view U.S. politics today and explore in depth how the public thinks about the quality of their political representation and the relationship between political actors and the people they represent.

The analysis is based on a survey of 8,480 adults from July 10 to July 16, 2023. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology.

Explore Americans’ views of the political system

This article draws from our major report on Americans’ attitudes about the political system and political representation, based on surveys conducted this summer. For more, read:

- The report chapters on money in politics and problems with the political system

- The full report

Large shares of the public see political campaigns as too costly, elected officials as too responsive to donors and special interests, and members of Congress as unable or unwilling to separate their financial interests from their work as public servants.

Here are seven facts about how Americans view the influence of money on the political system and elected officials, drawn from our recent report.

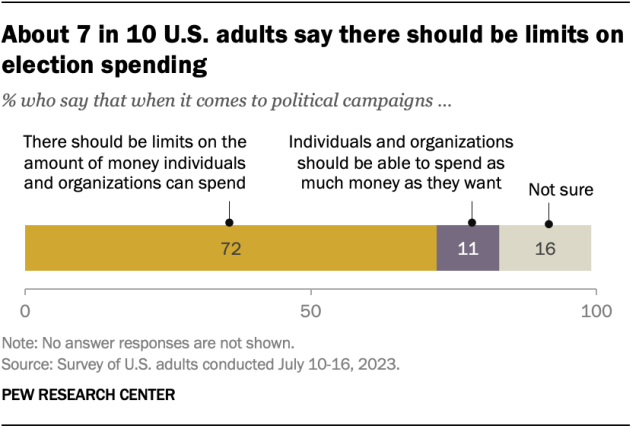

Most Americans favor spending limits for political campaigns. Roughly seven-in-ten U.S. adults (72%) say that there should be limits on the amount of money individuals and organizations can spend on political campaigns. Just 11% say individuals and organizations should be able to spend as much money as they want, and 16% are not sure.

Support for spending limits crosses ideological and demographic lines. Across all groups, by margins of at least three-to-one, more people say there should be limits than say there should not.

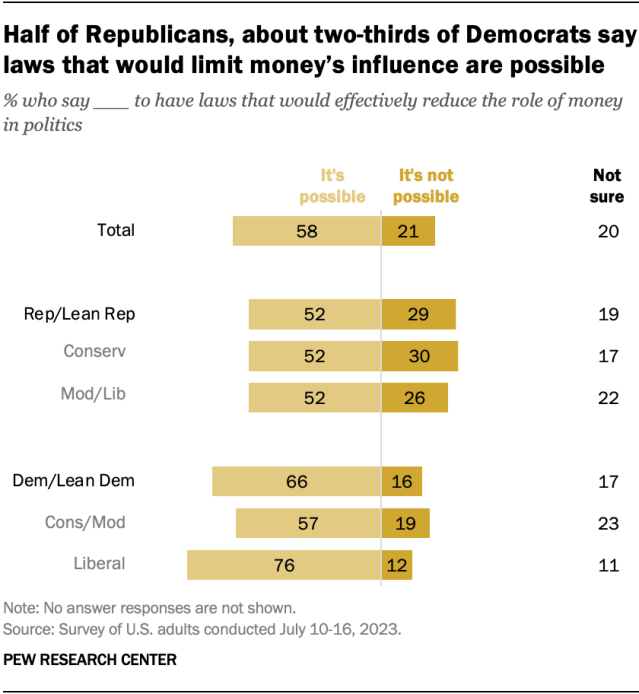

Nearly six-in-ten Americans say it’s possible to have laws that would effectively reduce the role of money in politics. About two-in-ten (21%) say it’s not possible to legislate this effectively. A similar share (20%) are not sure.

Liberal Democrats are particularly likely to say it’s possible to have laws that would reduce the role of money in politics. About three-quarters (76%) say this, compared with 57% of conservative or moderate Democrats and 52% of Republicans. There are no ideological differences on this question among Republicans.

In an open-ended question, 11% of Americans volunteer that the biggest problem with elected officials is that they’re too influenced by money in politics. An additional 9% describe elected officials as corrupt and 16% say they don’t work for the people they represent. These concerns are among the top responses to this question.

In a separate open-ended question about the political system as a whole, 15% say that the biggest problem is greed or corruption among elected officials.

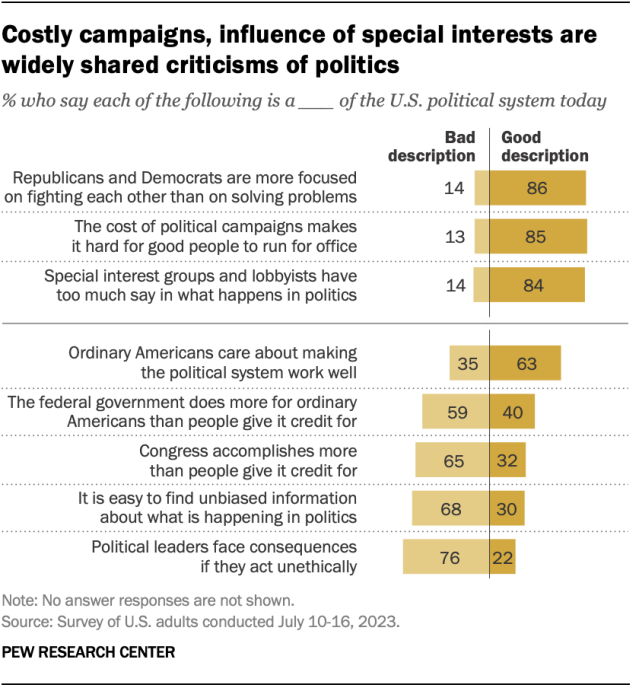

Americans overwhelmingly say that the cost of political campaigns makes it hard for good people to run for office. More than eight-in-ten Americans (85%) say this is a good description of the U.S. political system today, including identical shares of Republicans and Democrats.

A similar share of the public (84%) says that “special interest groups and lobbyists have too much say in what happens in politics” is a good description of the political system.

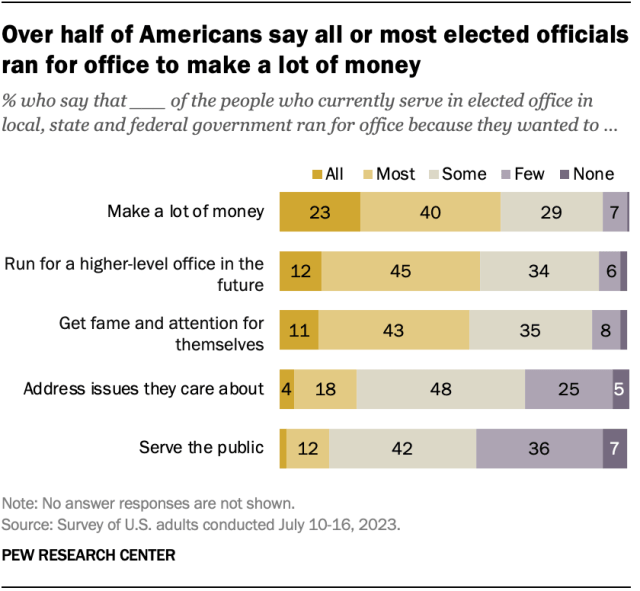

Self-interest – especially the desire to make money – is one of the main reasons people think most elected officials ran for office. More than six-in-ten (63%) say that all or most of the people who currently serve as elected officials ran for office to make a lot of money.

Majorities also say that all or most officials ran for office to seek a higher-level office in the future (57%) or to seek personal fame and attention (54%). Far fewer say that all or most elected officials ran to address issues they care about (22%) or to serve the public (15%).

Roughly eight-in-ten Americans say members of Congress do a bad job of keeping their personal financial interests separate from their work in Congress. The public also rates members of Congress poorly on listening to the concerns of people in their districts, working with members of the opposing party and taking responsibility for their actions.

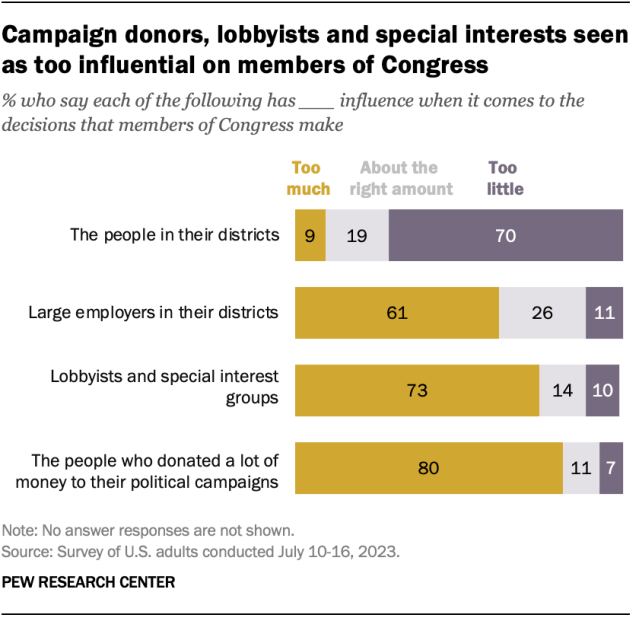

Campaign donors and lobbyists are widely viewed as having too much influence on members of Congress. Eight-in-ten U.S. adults say the people who donate money to political campaigns have too much influence on the decisions members of Congress make. And 73% say lobbyists and special interest groups have too much influence. Large majorities of Republicans and Democrats alike say campaign donors, lobbyists and special interest groups have too much influence.

By contrast, 70% of Americans say the people who live in representatives’ districts have too little influence over the decisions their representatives make.

Note: Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology.