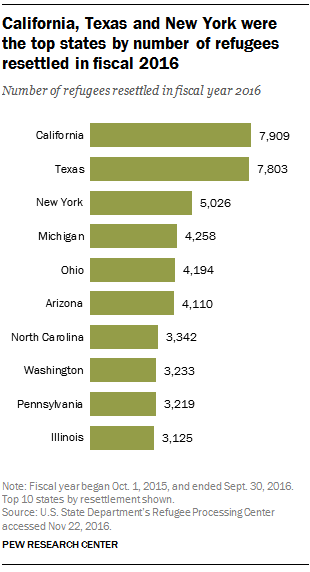

The U.S. admitted 84,995 refugees in fiscal year 2016, the most since 1999. But where they settled varied widely, with some states taking in large numbers and others very few, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. State Department data.

California, Texas and New York resettled the most refugees in fiscal 2016 (which began on Oct. 1, 2015, and ended Sept. 30, 2016), together taking in 20,738 refugees, or about a quarter (24%) of the U.S. total. Michigan, Ohio, Arizona, North Carolina, Washington, Pennsylvania and Illinois, which each received 3,000 or more refugees, rounded out the top 10 states by number of resettled refugees. Overall, 54% of refugees admitted to the U.S. in 2016 were resettled in one of these 10 states.

At the other end of the spectrum, some states and the District of Columbia took in few or no refugees in fiscal 2016. Arkansas, the District of Columbia and Wyoming resettled fewer than 10 refugees each, while two states – Delaware and Hawaii – took in none.

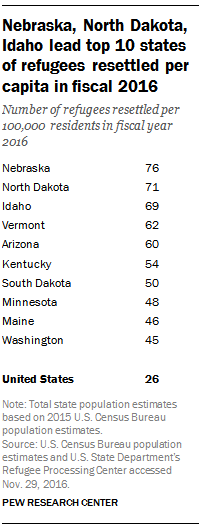

The states that took in the most refugees in fiscal 2016 are also some of the most populated states in the U.S. But on a per capita basis, some less populated states resettled more refugees than larger states. Over the past decade, Idaho has consistently ranked among the top states for refugees resettled per capita. And Minnesota had the highest single-year per capita rate of any state this decade, with 124 refugees resettled per 100,000 residents in fiscal 2005, the majority of which were from Laos (2,924).

In fiscal 2016, Nebraska (76), North Dakota (71) and Idaho (69) resettled the most refugees per 100,000 residents. Other states like Vermont (62), Arizona (60) and Kentucky (54) far exceeded the U.S. national average of 26 refugees per 100,000 residents.

For fiscal year 2016, President Barack Obama increased the maximum number of refugees admitted to the U.S. to 85,000, which was 15,000 more than in fiscal 2015. This resulted in nearly all states resettling more refugees in fiscal 2016 than they did in fiscal 2015 (Colorado, South Dakota, Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, West Virginia, Arkansas and Mississippi were the exceptions; in these states, the number of refugees resettled decreased from 2015).

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (16,370) was the top origin country among refugees resettled in 2016. Some 10% were resettled in Texas, 7% in Arizona and 6% in both New York and North Carolina.

However, Syrian refugees – the second-largest origin group with 12,587 resettled in fiscal 2016 – have garnered more attention from state leaders, with 31 governors opposing this group’s resettlement in their states. Even so, resettlement patterns of Syrian refugees across the states are similar to the national average. California had the largest number (1,450) of resettled Syrian refugees in fiscal 2016, followed by Michigan (1,374) and Texas (912).

The U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration reviews refugee applications based on referrals from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, U.S embassies, nongovernmental organizations or directly through direct access programs. Applications are screened by the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services and other federal agencies. Applicants who successfully navigate the application process are then invited to an in-person interview. Once approved, refugees undergo a health screening and most also go through cultural orientations outside of the U.S. The entire process can take up to 18 to 24 months.

For resettlement in the U.S., the International Organization for Migration and U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement work with voluntary agencies like the International Rescue Committee or Church World Service to resettle refugees. These voluntary agencies have offices across the country, dispersing refugees across many states. For example, Church World Service has resettlement programs in 21 states, while the International Rescue Committee has resettlement programs in 15 states. Once resettled, local nonprofits such as ethnic associations and church-based groups help refugees to learn English and job skills. After 90 to 180 days, financial assistance from federal agencies stops and refugees are expected to become self-sufficient.