Donald Trump may be leading in the race for the Republican presidential nomination, but much of the GOP’s establishment is mobilizing to try to block him. And should those efforts fail, many prominent Republicans are saying they won’t support Trump if he is the nominee. Some are even floating the idea of an anti-Trump third party.

Most times, even after fierce nomination battles and raucous conventions, parties have come together for the general-election fight. The bitter 1952 convention fight between Dwight Eisenhower and Sen. Robert Taft didn’t hurt Eisenhower that fall. In 1976, after Ronald Reagan fell just short of taking the GOP nomination from President Gerald Ford, he endorsed Ford in a memorable concession speech (although Ford went on to lose to Jimmy Carter in an exceedingly close race that November). And in 1968, even after a violence-marred convention and the third-party challenge of George Wallace, enough of the Democratic coalition came together in time for Hubert Humphrey to almost defeat Richard Nixon.

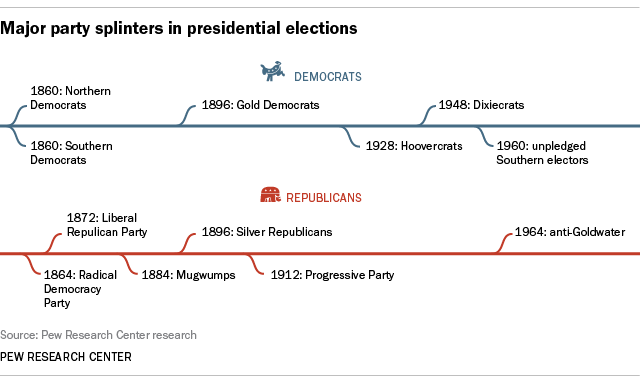

While it’s been a long time since a significant portion of a major party has rejected its own leading candidate, it’s hardly unprecedented in American political history. Here’s a rundown of notable splits, bolts, splinters and other major-party schisms, starting with the birth of the modern Democratic/Republican era. (Note: We excluded third-party movements, such as Wallace’s 1968 campaign and Ross Perot’s 1992 run, that originated outside the two major parties and weren’t explicit rejections of a particular nominee.)

1860: After no fewer than three conventions, Democrats split into Northern and Southern wings over the issue of slavery. Each wing nominated its own candidates for president and vice president, but the split virtually ensured the victory of Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln.

1864: A group of Radical Republicans, dissatisfied with Lincoln’s leadership during the Civil War, broke away and formed their own “Radical Democracy Party.” They nominated explorer and former Army general John C. Frémont, who had been the Republican candidate in 1856. But Frémont withdrew from the race in September because he was concerned the split could throw the election to the Democrats; in the end, Lincoln easily won a second term.

1872: Republicans unhappy with corruption within Ulysses S. Grant’s administration broke off and formed the “Liberal Republican Party.” They nominated Horace Greeley, editor of the New-York Tribune, for president, and the Democrats also adopted Greeley as their candidate. But Greeley was trounced by Grant at the polls and died less than a month later.

1884: Reform-minded Republicans known as “Mugwumps” refused to support GOP nominee James G. Blaine, who had a reputation for corruption, backing Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland instead. Cleveland narrowly defeated Blaine, though historians debate the extent to which the Mugwump split was responsible.

1896: Both major parties split over monetary policy. The Democratic platform and nominee William Jennings Bryan supported increasing the money supply through free coinage of silver, while the Republicans and their nominee, William McKinley, backed a “sound money” gold standard. (This was the campaign in which Bryan declared, “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”) That led “Silver Republicans,” mainly from Western silver-mining states, to break with McKinley and support Bryan. “Gold Democrats,” in contrast, feared that free silver would ruin the economy; they rejected Bryan and nominated their own pro-gold candidate. In one of the most dramatic and hard-fought elections up to that time, McKinley prevailed over Bryan.

1912: After former President Theodore Roosevelt failed to wrest the GOP nomination from his hand-picked successor, William H. Taft, he and his supporters bolted the Republicans and formed their own Progressive Party. As the Progressive nominee, Roosevelt performed better than any other third-party candidate in the post-Civil War era – he won 4.1 million popular votes (27.4%) and 88 electoral votes, out-polling Taft in both cases. But the bitter GOP split cleared the way for Woodrow Wilson to become just the second Democrat in 56 years to win the White House.

1928: Many Democrats in the South refused to support New York Gov. Al Smith as the party’s nominee, either because Smith was a Catholic, a “wet” on Prohibition, a product of New York’s Tammany Hall machine, or all three. Enough white Southern Democrats – or “Hoovercrats” – voted Republican that year that Smith carried only six states in the normally Democratic “Solid South.”

1948: Southern Democrats upset at President Harry S. Truman’s civil-rights program walked out of the Democratic convention and formed the States’ Rights Democratic Party, known as “Dixiecrats.” The Dixiecrats nominated South Carolina Gov. Strom Thurmond for president and adopted a strongly pro-segregation platform. Truman also faced a challenge from his left in the Progressive Party campaign of former Vice President Henry A. Wallace. Despite the two splinters, Truman won an upset re-election victory; Thurmond received 1.2 million popular votes and 39 electoral votes, all from Southern states, while Wallace got almost as many popular votes but no electoral votes.

1960: In reaction against Democratic nominee John F. Kennedy and the national party’s civil-rights platform, several Southern states ran slates of “unpledged” presidential electors, hoping to throw the election into the House of Representatives. In the end, though, only 14 unpledged electors (from Alabama and Mississippi) won, not enough to hold the balance between Kennedy and GOP nominee Richard Nixon. Rather than vote for Kennedy, the unpledged electors cast their electoral votes for Virginia Sen. Harry F. Byrd.

1964: After Sen. Barry Goldwater won the Republican nomination, many moderate Republicans (including Govs. Nelson Rockefeller of New York and George Romney of Michigan) refused to support him. The New York Herald Tribune, long the preeminent voice of the GOP’s Eastern establishment, endorsed President Lyndon Johnson over Goldwater. Goldwater lost in one of the biggest landslides in U.S. history.