“The Next America: Boomers, Millennials, and the Looming Generational Showdown,” by Paul Taylor and Pew Research Center, is being released this week in a paperback edition that includes nearly 100 pages of new text, charts and updates to the original 2014 hardcover edition. Here, Paul Taylor shares eight takeaways from the book’s all-new opening chapter, “Political Tribes.”

In an era of head-snapping racial, social, cultural, economic, religious, gender, generational and technological change, Americans are increasingly sorted into think-alike communities that reflect not only their politics but their demographics. The result has been a rise in identity-based animus of one party toward the other that extends far beyond the issues. These days Democrats and Republicans no longer stop at disagreeing with each other’s ideas. Many in each party now deny the other’s facts, disapprove of each other’s lifestyles, avoid each other’s neighborhoods, impugn each other’s motives, doubt each other’s patriotism, can’t stomach each other’s news sources, and bring different value systems to such core social institutions as religion, marriage and parenthood. It’s as if they belong not to rival parties but alien tribes.

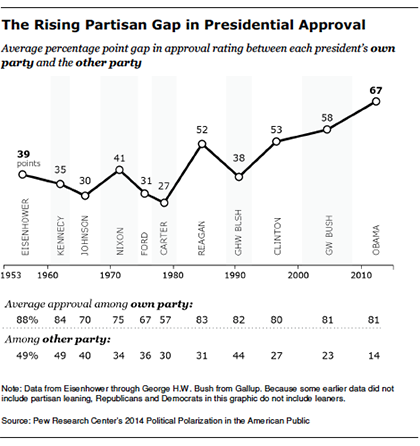

And their candidates in 2016 might seem to be running for president of different countries. As the chart above illustrates, the partisan gap in how Americans evaluate their presidents is wider now than at any time in the modern era.

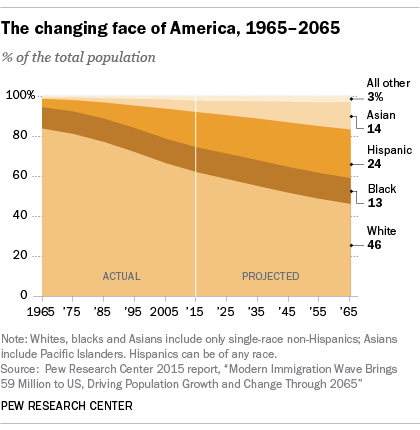

This political sorting has roots in two simultaneous demographic transformations that America is undergoing. The U.S. is on its way to becoming a majority nonwhite nation, and at the same time, a record share of Americans are going gray. Together these overhauls have led to stark demographic, ideological and cultural differences between the parties’ bases.

We now have one party that skews older, whiter, more religious and more conservative, with a base that’s struggling to come to grips with the new racial tapestries, gender norms and family constellations that make up the beating heart of the next America. The other party skews younger, more nonwhite, more liberal, more secular, and more immigrant- and LGBT-friendly, and its base increasingly views America’s new diversity as a prized asset.

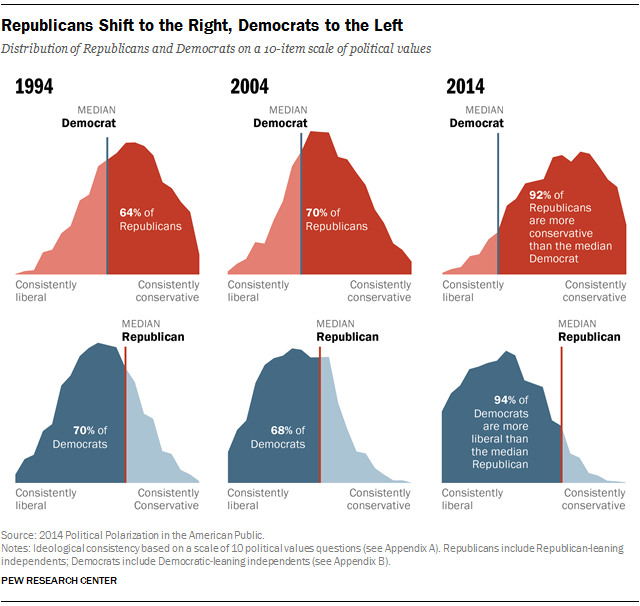

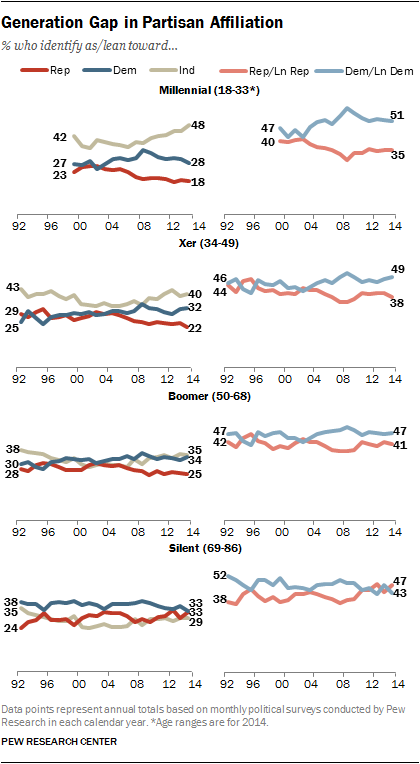

At the turn of the century, there was no partisan difference in the votes of young and old. But in recent elections, there has been a huge generation gap at the polls. And Democrats and Republicans have become much more ideologically polarized.

Today 92% of Republicans are to the right of the median Democrat in their core social, economic and political views, while 94% of Democrats are to the left of the median Republican, up from 64% and 70% respectively in 1994. The same 2014 Pew Research Center study also found a doubling in the past two decades in the share of Americans with a highly negative view of the opposing party.

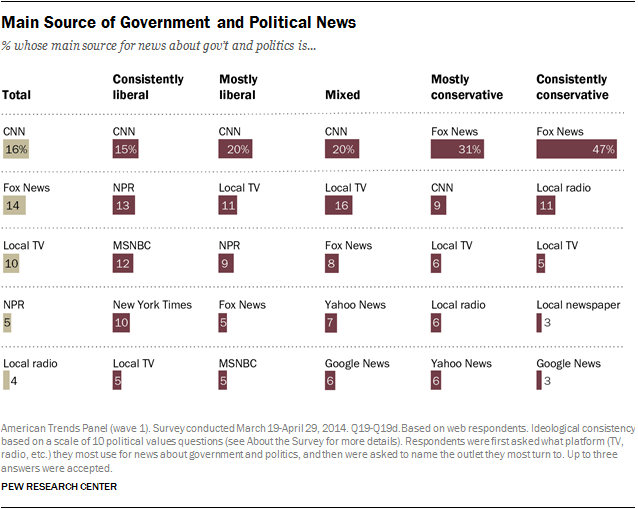

The cleavages between the political tribes spill beyond politics into everyday life. Two-thirds of consistent conservatives and half of consistent liberals say most of their close friends share their political views. And liberals say they would prefer to live in cities while conservatives are partial to small towns and rural areas. In their child-rearing norms, conservatives place more emphasis on religious values and obedience, while liberals are more inclined to stress tolerance and empathy. And in their news consumption habits, each group gravitates to different sources.

To be clear, not all of America is divided into these hostile camps. Even as partisan polarization has deepened, more Americans are choosing to eschew party labels. This group is heavily populated by the young, many of whom are turned off by the cage match of modern politics. They are America’s most liberal generation by far, but when asked to name their party, nearly half say they are independents. No generation in history has ever been so allergic to a party label.

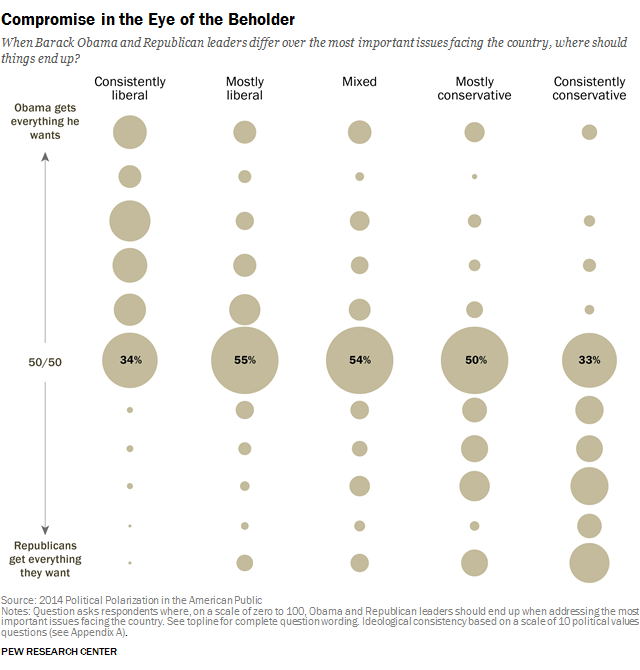

Identity-based hyperpartisanship is thriving at a time when a majority of Americans tell pollsters they’d like to see Washington rediscover the lost art of political compromise. As ever, many Americans are pragmatists, ready to meet in the middle.

Yet nowadays these Americans are the new silent majority. They don’t have the temperament, inclination or vocal cords to attract much attention in a media culture in which shrill pundits and 140-character screeds set the tone. Those most averse to political compromise are ideologically consistent conservatives and liberals, majorities of whom want their side to prevail.

Congress’ members are more polarized by party than at any time since the Reconstruction Era. And recent elections have produced something else unprecedented in American political history – one party winning the popular vote in five of the past six presidential contests even as the other party has recently run up its biggest congressional and statehouse majorities in a century.

The Democratic base, dubbed the “coalition of the ascendant” by journalist Ronald Brownstein, is often the coalition of the unengaged, especially during non-presidential elections. In 2014, for example, just 19.9% of 18- to 29-year-old citizens voted, a record low. The old turning out in force more than the young is nothing new – that seems hard wired into the human life cycle. This matters little when the generations vote alike, but it makes a huge difference when, as now, they don’t.

Thus we have the alternating red and blue election outcomes of the recent past, with President Obama’s victories in the big turnout years of 2008 and 2012 playing hopscotch with the GOP romps in the low turnout midterms of 2010 and 2014. This in turn has contributed to a Washington that’s paralyzed by gridlock and a hothouse for the sort of rancor that can fire up the hyperpartisans but can also send nonpartisans farther off to the political sidelines. And so the cycle of mean-spirited, broken politics perpetuates itself.

Might 2016 be the year we break the fever? So far it’s not looking that way. The public remains in a foul mood, frustrated by stagnant incomes, a shrinking middle class and gruesome global terrorism. Just 19% say they trust the government to do what’s right. Moreover, most Republicans and many Democrats say they believe that, on the issues that matter most to them, the other side is winning. And not since the early 2000s has a majority of the public said the nation is on the right track, making these past dozen years the longest sustained stretch of national pessimism since the onset of polling.

[chart id=”320660″]

Politics is never static, which means today’s state of affairs isn’t necessarily a template for the future. This campaign has already illuminated deep fissures not just between both parties but within them. A lot of political business will get transacted between now and November. No matter what the outcome, the political firmament is likely to look different next year.

The most hopeful take on this long season of political discontent comes from our nation’s most astute early observer, Alexis de Tocqueville, who noted nearly two centuries ago that American democracy isn’t as fragile as it looks; confusion on the surface masks underlying strengths.