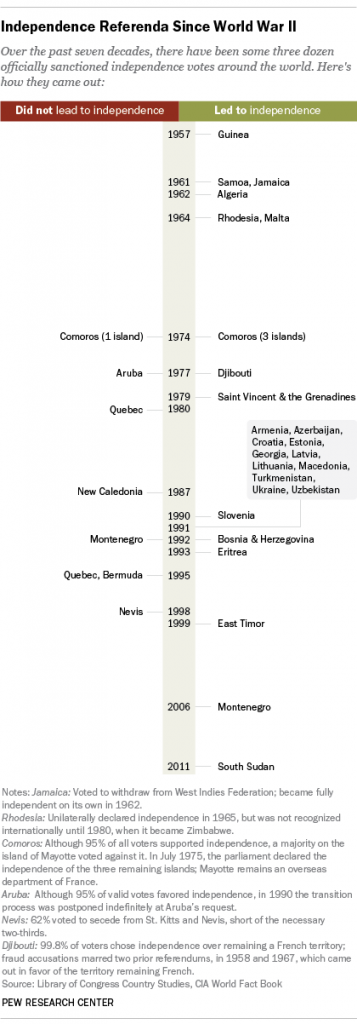

This week’s referendum on whether Scotland should leave the United Kingdom appears to be a lot closer than many observers had expected. That, and the fact that the Sept. 18 vote is taking place in a context free of war, chaos or political violence, makes it stand out from most of the three dozen or so other officially sanctioned independence referendums in the post-World War II era.

The spectacle of the hotly contested Scottish referendum made us wonder how it compared with other similar votes over the years. After consulting several sources — from contemporary news sources to the Library of Congress’ “Country Studies” series of backgrounders –one thing we learned was that there haven’t been all that many referendums comparable to the Scottish vote. (Our analysis extended only to officially recognized independence referendums among the 193 United Nations members or their former colonial possessions; unofficial votes and votes in non-member states and territories of disputed sovereignty weren’t examined.)

During the great era of decolonization that followed the end of the war, only a handful of nations achieved independence via a popular vote. The west African nation of Guinea represents one such instance: In 1958, France held referendums in its colonies on whether to approve the new Fifth Republic constitution, which also established a French Community to replace the decaying empire. Guinea was the only territory where voters rejected the constitution, 95.2% to 4.8%, in favor of immediate independence. (The French Community, however, didn’t last very long, with most of its members withdrawing in the early 1960s.) Bahrain became independent in 1971 following not a referendum, but a United Nations survey that concluded “the overwhelming majority” of Bahrainis favored it.

But in most cases, European colonial powers negotiated with the leaders of indigenous liberation movements or local elites — often during or following an armed struggle — with no provision for a popular vote on independence. Algeria, for instance, formally won its independence after a 1962 referendum, but that nearly unanimous vote followed a bloody eight-year war with France (which considered Algeria an integral part of itself rather than a colony).

Independence referendums remained uncommon throughout the 1970s and 1980s, but that changed in the 1990s during the collapse of the Soviet Union and other Communist-bloc countries: Eight of the republics that declared independence from Moscow, and all five republics that left Yugoslavia, did so via popular vote. (In at least one case, the vote was truly superfluous: Uzbekistan voted overwhelmingly to leave the Soviet Union on Dec. 29, 1991, three days after the Soviet Union ceased to exist.)

Most successful postwar independence referendums for which we could find results were essentially foregone conclusions: In only three cases (Jamaica 1961, Malta 1964 and Montenegro 2006) did the pro-independence vote fall below 60%, and 17 countries recorded pro-independence votes greater than 90%.

However, not all independence votes succeed. Most famously, Quebec has twice rejected separating from Canada, although the 1995 vote was very close, with 49.4% voting “yes” and 50.6% voting “no”. That same year, in a rather less dramatic and closely watched vote, 74% of Bermudians voted against independence. In 1987, voters in New Caledonia, a French island territory in the South Pacific, overwhelmingly (98.3% to 1.7%) rejected independence; a new vote will be held sometime before 2018.

Sometimes even yes-no referendums haven’t provided clear answers. In December 1974, 94.5% of voters in the four-island Comoros chain voted for independence from France. Opposition was concentrated on the island of Mayotte, where 63% voted against independence. The three other islands declared independence the following summer, but France retained control of Mayotte; it remains a French overseas department to this day.

Scotland’s vote, which is being held pursuant to an agreement between the Scottish and UK governments, is attracting keen interest from other separatist movements, from Flanders and Frisia to Taiwan and Texas. And it may not be the last one held this year: Catalonia’s regional government has called for a Nov. 9 vote on independence, although Spain has said any such referendum would be illegal and void. In July, the leader of Iraq’s autonomous Kurdish region told the BBC he planned to hold an independence vote in “a matter of months.”