The United States has experienced a spate of public killing sprees in recent weeks. In June alone, shootings at Seattle Pacific University, Reynolds High School in suburban Portland, and in Las Vegas left a total of five people dead and three wounded (excluding the shooters). Last month, a 22-year-old college student in southern California stabbed his three roommates to death, then shot and killed three more people and wounded 13 others before shooting himself.

Which makes us wonder: Are school shootings and other killing sprees really more common nowadays? The available data don’t offer clear evidence, due to issues of timeliness, reliability or both.

The most frequently cited source for data on mass killings is the Federal Bureau of Investigation, yet it falls short in several ways. The agency relies on voluntary reporting by local police agencies; as a result, USA Today reported last year, the FBI data had only about a 61% accuracy rate — missing some crimes entirely and miscategorizing others. Besides such errors, Florida doesn’t report homicides to the FBI at all, and Nebraska and Washington, D.C., only started doing so in 2009.

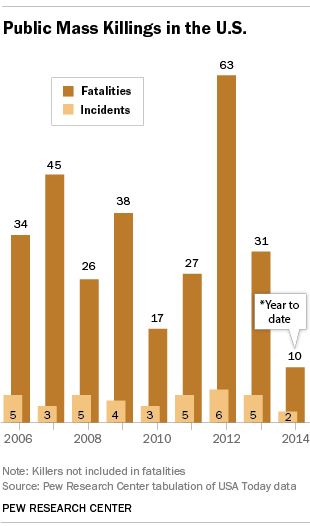

A more comprehensive database maintained by USA Today lists 38 public mass killings since 2006; all but four were shootings. Since 2006, the number of public mass killings each year has varied between 3 and 6. The year 2012, which saw both the Aurora, Colo., and Newtown, Conn., massacres, had by far the most total fatalities (63).

Another problem arises in defining and counting such horrific events. Both USA Today and the FBI define a “mass killing” as an incident with at least four victims, excluding the killer. (A March 2013 report by the Congressional Research Service, which identified 78 public mass shootings in the U.S. between 1983 and 2012, used a similar definition.) That means none of this month’s killings, terrible as they were, will appear in those counts.

When it comes to another category — school shootings — timely, consistent, broadly accepted data are even harder to come by. Everytown for Gun Safety, a pro-gun control group backed by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, lists at least 44 school shootings since the December 2012 massacre at Newtown’s Sandy Hook Elementary. A map based on Everytown’s research, which originally showed 74 school shootings, spread quickly online last week.

[was]

[or]

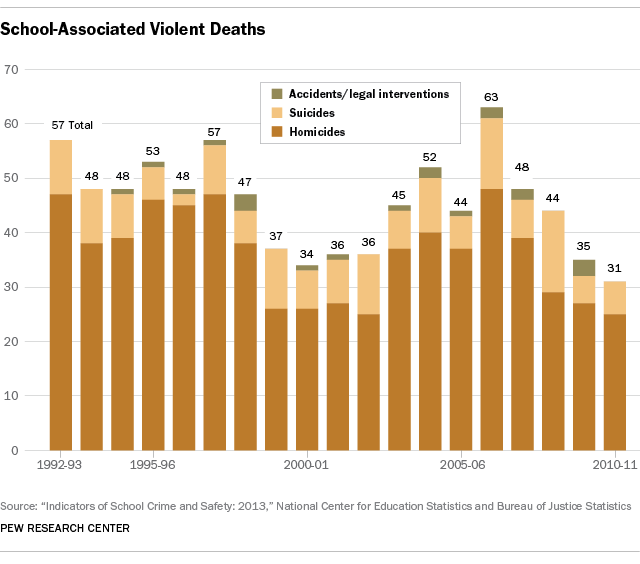

However, the NCES data only run through the 2010-11 school year. That year there were 31 “school-associated violent deaths,” the fewest since the report’s coverage began in 1992-93. But that was before 20 students and six adults were killed at Sandy Hook. Based on preliminary counts from media reports, the report indicated that there were 17 subsequent school-associated violent deaths — 11 homicides and six suicides — between Sandy Hook and November 2013.

As the report notes, such incidents are as rare as they are tragic. In 2010-11, for instance, 11 children and youths (ages 5 to 18) were murdered at school, less than 1% of the 1,336 total homicides among that age group that year; suicides at school were even rarer.

And the overall gun homicide rate has fallen sharply from its early-1990s peak, according to a Pew Research Center report from last year. The overall rate of gun homicides was 3.6 per 100,000 people in 2010, the most recent year available, a decline from 7 per 100,000 in 1993. The 2010 rate was about the same level as the early 1960s. The absolute number of gun homicides also was down, to 11,078 in 2010, compared with 18,253 in 1993. (All those figures came from analyses of death certificates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)