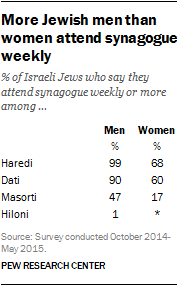

Israeli Jews vary enormously in their religious observance, with major differences tied inherently to the four major Jewish identity groups. The share who say they go to religious services at a synagogue at least once a week, for example, ranges from nearly all Orthodox Jewish men (Haredi and Dati) and majorities of Orthodox women to very few secular (Hiloni) men and practically no Hiloni women.

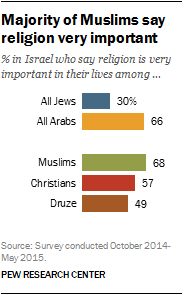

Overall, Jews are less religious than members of Israel’s other major faith communities – Muslims, Christians and Druze – by most comparable measures. For instance, fully 68% of Israeli Muslims say religion holds a very important place in their lives, followed by 57% of Christians, 49% of Druze and 30% of Jews.

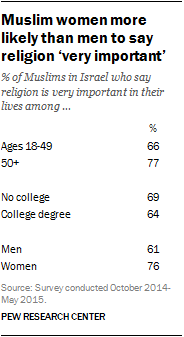

This overall picture – in which Israel’s minority faith groups are, on average, more religious than Israeli Jews – is more complex than it seems. One factor is gender: Generally speaking, women display higher levels of religious commitment than men among Muslims in Israel. (Even though men attend mosque at higher rates than women, more women say they pray frequently and say religion is very important in their lives.) But among Jews, the opposite is true: Men, on average, display higher levels of observance than women.

In part, this may be because of differences in religious requirements for men and women according to Jewish law (e.g., men are expected to pray and attend synagogue more often than women). But men also are more likely than women to say that, overall, religion is very important to them. These differences are particularly pronounced among Haredim and Datiim but are also prevalent among Masortim.

Another major difference in demographic patterns between Jews and Muslims is age. While Jews belonging to younger and older age groups vary little in their overall religious commitment, younger Muslims tend to be less observant than older Muslims. For example, Muslims between the ages of 18 and 49 are less likely than those ages 50 and older to attend mosque weekly or pray daily.

Most Haredim, Datiim attend synagogue weekly, while most Hilonim never attend

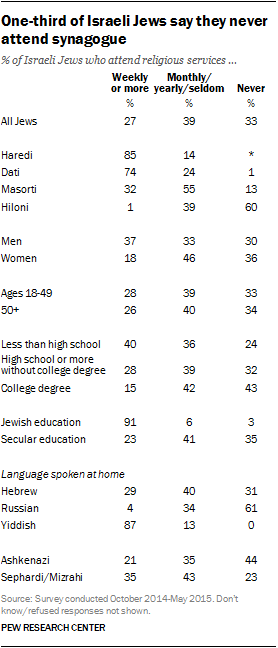

Roughly a quarter of Israeli Jews say they attend synagogue on a weekly basis (27%), while 39% say they attend on a monthly, yearly or infrequent basis. A third of Jews in Israel (33%) say they never go to synagogue.

Regular synagogue attendance is one of the fundamental behavioral differences between Jewish subgroups in Israel. While the vast majority of Haredim (85%) attend religious services weekly, almost no Hilonim (1%) do. And while a majority of Hilonim (60%) say they never go to synagogue, virtually no Haredi respondents say this.

Weekly synagogue attendance is also the norm among Datiim; 74% say they attend synagogue weekly. Compared with other Jewish subgroups, Masortim are less uniform in their synagogue attendance. A plurality (55%) say they attend synagogue monthly, yearly or seldom, while about a third (32%) say they attend weekly. About one-in-ten Masorti Jews (13%) say they never attend synagogue.

Self-reported rates of weekly synagogue attendance are very low (4%) among Jews who primarily speak Russian at home. A majority of Jews who speak Russian at home say they never attend synagogue (61%).

Jewish men overall are considerably more likely than women to say they go to synagogue on a weekly basis (37% vs. 18%). This gender difference is seen among Haredi, Dati and Masorti men and women; few Hiloni men or women report attending synagogue weekly or more.

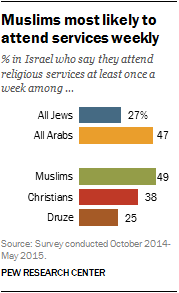

Israeli Jews are less likely than Arabs in Israel to participate in weekly worship services. Among Arabs, nearly half of adults (47%) say they attend services weekly.

This gap is largely driven by Israeli Muslims, 49% of whom report attending mosque at least weekly. In fact, among Muslims, about a quarter of adults (27%) report attending mosque more than once per week. Among Israeli Jews, 16% of adults say they go to synagogue more than once a week.

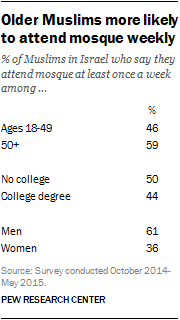

Among Muslims – as among Jews – worship attendance is more common among men than women. In part, this is because in both traditions, worship service attendance is more incumbent upon men than it is among women. About six-in-ten Muslim men (61%) report attending mosque on at least a weekly basis, compared with 36% of Muslim women.

While Jews differ very little by age when it comes to synagogue attendance, among Muslims, older adults are more likely than younger people to attend weekly worship services.

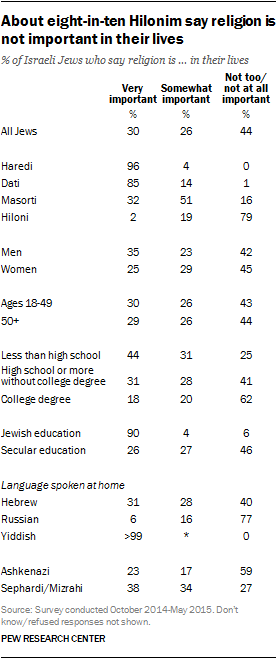

Plurality of Israeli Jews say religion is not important to them

As with synagogue attendance, the importance of religion in the lives of Israeli Jews varies enormously by subgroup.

Haredim nearly universally say religion is very important in their lives. Hilonim are at the opposite end of the spectrum, with just 2% reporting that religion is very important to them and about eight-in-ten (79%) saying it is either “not too” or “not at all” important.

A strong majority of Datiim (85%) say religion has a very important place in their lives. And Masortim again occupy the religious middle; 51% say religion is “somewhat” important in their lives, while about one-third (32%) say religion is very important to them and roughly one-in-six (16%) say religion is not too or not at all important to them, personally.

Overall, Jewish men are somewhat more likely than Jewish women to say religion is very important in their lives (35% vs. 25%). This difference is largely a result of a large gap between Masorti men and women. Masorti men are nearly twice as likely as Masorti women to say religion has high importance in their lives (41% vs. 23%). Within the other Jewish subgroups, men and women are about equally likely to say religion is very important in their lives.

Religion is generally more important to Israeli Jews who have lower levels of formal education; most Jews with a college degree (62%) say religion is not too or not at all important to them.

In Israel, Arabs are more than twice as likely as Jews to say religion is very important in their lives. Roughly two-thirds of Arabs (66%) say religion has high importance in their lives, compared with 30% of Jews. Arabs are far less likely than Jews to say religion is not too important or not at all important to them, personally; just 5% of Arabs say this, compared with 44% of Jews.

Muslims are especially likely to say religion is very important to them (68%). But Israeli Christians (57%) and Druze (49%) also are more likely than Jews as a whole to place high importance on religion.

Among Jews, men are more likely than women to say religion is very important in their lives. But among Muslims, the opposite is true; 76% of Muslim women in Israel say religion has high importance in their lives, compared with 61% of men.

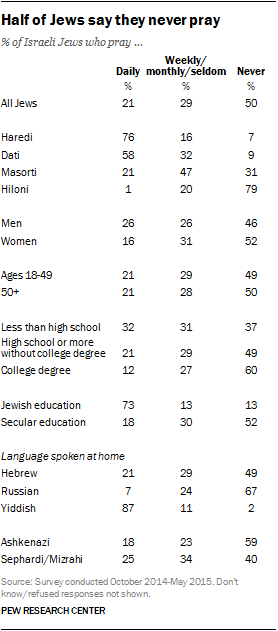

Roughly three-quarters of Haredim pray daily, while similar share of Hilonim never pray

As with synagogue attendance and importance of religion, prayer habits differ substantially among religious subgroups of Jews in Israel.

The majority of Haredim (76%) say they pray every day, while relatively few (7%) say they never pray. The vast majority of Hilonim, meanwhile, say they never pray (79%), while just 1% pray daily.

A slim majority of Datiim (58%) pray once a day or more. Masortim have more varied prayer habits. A plurality of Masortim (47%) say they pray on a weekly, monthly or infrequent basis. An additional 21% pray on a daily basis, while 31% say they never pray.

As on other measures of religious observance, these patterns extend to other demographic groups in Israeli society. For instance, Israeli Jews who primarily speak Yiddish are especially likely to pray often, while Russian-speaking Jews are unlikely to do so. Similarly, prayer is far more common among Israeli Jews who received their highest education from a religious institution than it is among those who received their highest training from a secular institution. There also are gaps among Jews with different levels of formal education overall; college graduates are less likely than others to report praying daily.

Older and younger Israeli Jews pray at about the same rates.

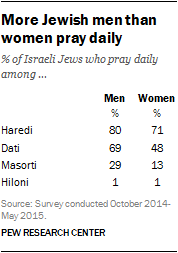

In Judaism, daily prayer is more incumbent upon men than women. Perhaps for this reason, Jewish men across different subgroups in Israel generally are more likely than Jewish women to say they pray daily.

The gender gap on prayer is especially pronounced among Datiim. Roughly seven-in-ten Dati men (69%) say they pray daily, compared with about half of Dati women (48%). But there also are differences between men and women among Haredim (80% of Haredi men pray daily vs. 71% of women) and Masortim (29% vs. 13%).

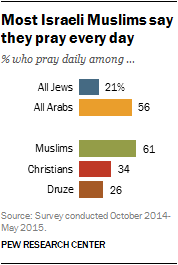

A slim majority of Israeli Arabs (56%) say they pray on a daily basis, compared with 21% of Israeli Jews who say the same.

This gap is largely due to high rates of prayer among Muslims. About six-in-ten Muslims in Israel (61%) say they pray at least once a day, including 52% who pray all five prayers. Among Christians, the rate of daily prayer (34%) is lower than among Muslims but higher than among Jews. Israeli Druze are about as likely as Jews to pray every day (26% vs. 21%).

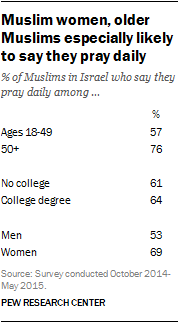

Unlike the Jewish community, where there are few differences by age when it comes to rates of daily prayer, older Muslims are more likely than younger adults to say they pray daily. The vast majority of Muslims ages 50 or older (76%) pray every day, compared with 57% of Muslim adults under 50.

Muslims also differ from Jews when it comes to patterns in prayer by gender. Among Jews, more men than women say they pray every day, while among Muslims, more women than men report praying on a daily basis (69% vs. 53%).

Half of Israeli Jews are absolutely certain of God’s existence

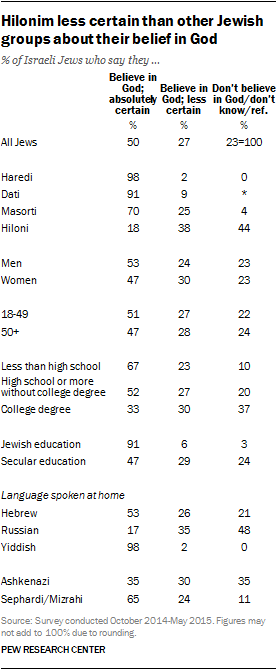

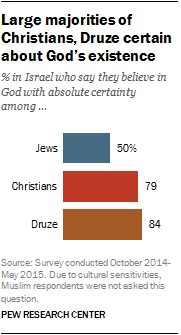

Half of Israeli Jews (50%) say they believe in God with absolute certainty. As with other standard measures of religious observance, belief in God varies considerably by Jewish subgroup, ethnic background, primary language and education level and type.

Hilonim, who make up 49% of Israeli Jews, stand apart from Haredim, Datiim and Masortim on this issue. While majorities in other groups are convinced of God’s existence – including overwhelming majorities of Haredim (98%) and Datiim (91%) – among Hilonim, only about one-in-five (18%) say they believe in God with absolute certainty. More than a third of Hilonim (38%) say they believe in God but are less than absolutely certain, while 44% say they do not believe in God or they do not know if God exists.

About nine-in-ten Israeli Jews who received their highest education from a religious institution (91%) say they are absolutely certain God exists, while about half of those who received their highest training from a secular institution (47%) share this view. Jews also vary considerably by linguistic background; just 17% of Russian-speaking Jews are absolutely convinced of God’s existence. By contrast, Yiddish speakers are nearly universally certain about God’s existence (98%). Hebrew speakers fall somewhere in between, with 53% convinced that God exists.

There also is a considerable gap on this question by ethnicity. Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews are more likely than Ashkenazim to say they are absolutely certain of God’s existence (65% vs. 35%), while Ashkenazi Jews are much more likely to say they do not believe in God or do not know if they believe in God (35% vs. 11%).

Across Israel, belief in God is higher among Christians and Druze than among Jews. Nearly all Druze (99%) believe in God, including 84% who are absolutely certain of their belief. Among Christians, 94% believe in God, including 79% who say they are absolutely certain.

Due to cultural sensitivity over the very idea that God’s existence potentially could be denied, Muslims were not asked this question. Instead, Muslims were asked if they believe in the shahada, a declaration of faith in one God (Allah) and his Prophet Muhammad. Like Muslims elsewhere around the world, Israeli Muslims nearly universally say they believe in Allah and his Prophet Muhammad (97%). Muslims across different age, gender and education groups are about equally likely to affirm the shahada.