Not so long ago, most surveys measured a person’s gender either by observation or with a question that had two response options – “male” or “female.” Survey research, like society more generally, rarely allowed for the possibility that a person’s gender might not match the sex on their birth certificate, or that they might not describe themselves as a man or a woman at all. Similarly, social conventions combined with the presumed small size of the population that is not heterosexual meant surveys rarely asked about sexual orientation.

While Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey’s studies of sexual behavior in the 1940s and 1950s were based on interviews that included questions about same-sex attraction and behavior, questions about sexual orientation were not common in surveys prior to the 1980s. Public health researchers attempting to combat the AIDS epidemic began regularly asking questions about sexual orientation and behavior, and such questions slowly became more common in general public surveys.

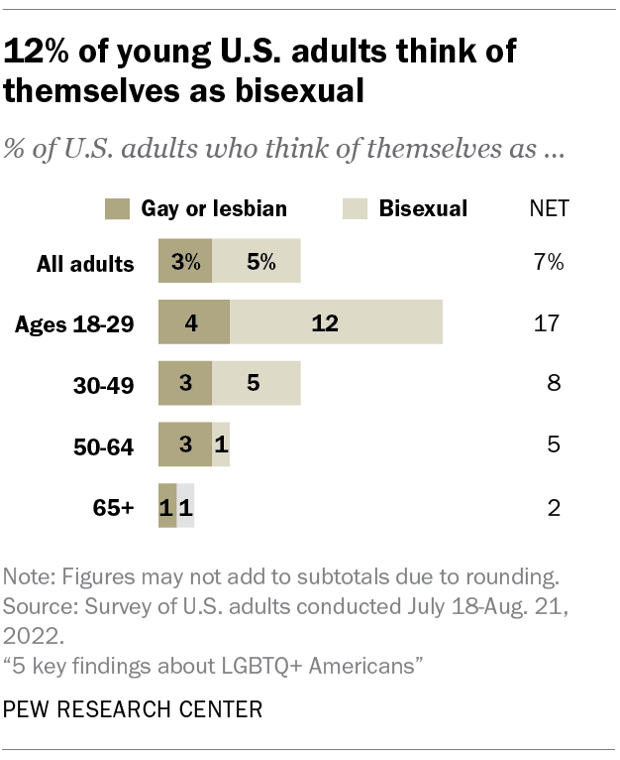

Today, gender and sexual orientation are topics on the cutting edge of survey measurement. As of 2022, more than four-in-ten U.S. adults report that they personally know someone who is transgender, and one-in-five say they know someone who is nonbinary – that is, they are neither a man nor a woman, or aren’t strictly one or the other. Surveys show that the share of U.S. adults who indicate that they are LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer) has gradually increased over the past decade. Social science and health researchers are particularly interested in accurately capturing data on gender and sexual orientation to learn more about how Americans identify, their experiences in society, health outcomes, wages and more.

Accurately measuring gender and sexual orientation poses several challenges to survey researchers. An obvious one is that some people may not be comfortable identifying as LGBTQ in a survey due to the fear of discrimination or social stigma. This hesitation is less of a concern, but may still be present, in the context of a confidential survey that doesn’t use live interviewers.

Another issue is that some of the terminology that LGBTQ or nonbinary individuals use to describe themselves may be unfamiliar to many Americans. For example, a 2022 Center survey found that 21% of Americans said that they had heard nothing at all about people not identifying as a man or a woman and instead using terms like “nonbinary” or “gender-fluid” to describe themselves. And some people simply reject the idea that someone’s gender can be impermanent and are offended by questions that suggest otherwise.

How we ask about gender

For most of the telephone surveys we conducted over the past three decades, interviewers either recorded the assumed sex of the respondent based on their voice, or selected a respondent by asking specifically for a male or a female and recorded the person’s sex based on that selection, typically without asking for further confirmation. Until recently, the standard demographic battery on most of Pew Research Center’s self-administered surveys used a binary question that didn’t make a clear distinction between sex and gender. (“Are you male or female?”)

In 2020, we undertook research to determine a better way of asking about sex and gender on our surveys. Because we frequently look at men and women as key subgroups when analyzing our survey results, it was important to find the right way of asking this critical demographic question, and we recognized that the language we had been using didn’t capture the way some of our respondents describe themselves.

“Reconfiguring the gender question required a balancing act. We had to make sure that our respondents would recognize themselves in the categories we offered and know which one to pick.”

Reconfiguring the gender question required a balancing act. We had to make sure that our respondents would recognize themselves in the categories we offered and know which one to pick. Offering a wide range of options to capture the many ways people describe themselves might be helpful for a small group of respondents but risks confusing others.

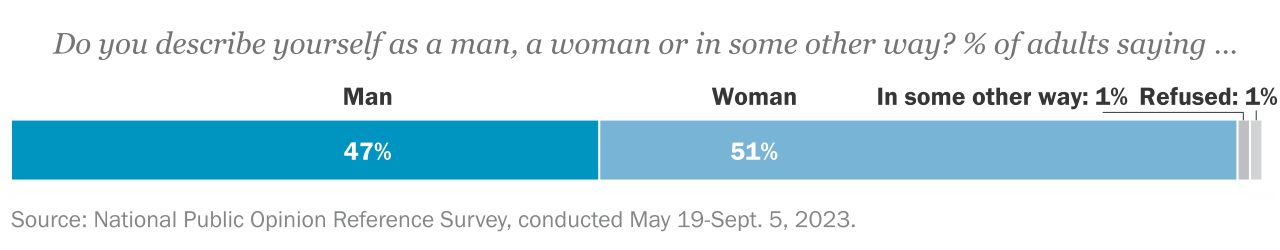

After testing several new options for gender and sex questions, we settled on asking, “Do you describe yourself as a man, a woman or in some other way?” This clarifies that we are asking about gender (by asking how they describe themselves and using the terms “man” and “woman,” which are usually associated with gender) and allows those who are neither a man nor a woman to indicate this without introducing terminology that some respondents may be unfamiliar with.

This approach comes with some complications, though. The share of people who describe themselves “in some other way” besides man or woman is so small that we cannot report their views separately in any typical survey (though their responses are always included in the general population figures in our research). Also, extra care must be taken to ensure respondents’ confidentiality when releasing our datasets to the public, since nonbinary adults are a small share of the population and may or may not be open about their gender with people in their lives.

How we ask about sexual orientation

Our sexual orientation question has also changed in small ways over the years, though our approach closely resembles questions asked on government surveys and others.

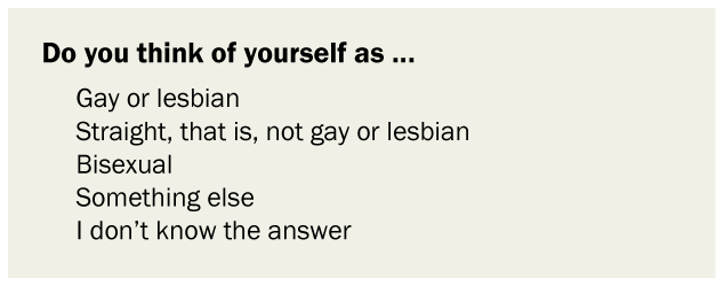

One of our main purposes in developing this question is to use plain language that will be recognized by as many participants as possible. This is why we avoid terms like heterosexual and homosexual and say “straight, that is, not gay or lesbian” in case respondents don’t know what “straight” means. (This terminology comes with limitations. “Straight, that is, not gay or lesbian” assumes that being straight is the norm. It also doesn’t take into account that there are other sexual orientations besides straight, gay and lesbian.)

Being conscious of terminology may be especially important for surveys translated into Spanish, where “straight” does not have a universally understood translation. Even the premise of the question is framed using plain language – we simply ask how respondents think of themselves, rather than, “What is your sexual orientation?” This is similar to the way we ask how respondents describe themselves to learn their gender identity.

In this question, we also allow respondents to select “something else” or “I don’t know the answer” in case the response options provided don’t fit, or if they are not sure of their sexual orientation. However, we do not include responses of “something else” as part of the lesbian, gay and bisexual population because studies have shown that most people who select this are protesting the question rather than indicating a sexual orientation.

Digging deeper on gender identity and sexual orientation

In a typical survey sample, the number of people who are transgender or nonbinary is too small for separate tabulation. Research that focuses on these and other gender minorities require larger samples and more detailed measures. Choosing a set of measures comes with a few challenges.

Psychologists and health researchers make a distinction between gender and sex, though our research shows that much of the U.S. public rejects the idea that these can be different. Researchers in this field define the terms this way:

- Sex refers to the biological characteristics that make one male or female, such as chromosomes, hormones, reproductive organs and secondary sex characteristics like breasts and facial hair. Survey questions may ask respondents’ “sex assigned at birth” and may offer “male” and “female” as response options – though this could change as some states begin issuing birth certificates that specify intersex or other options for sex.

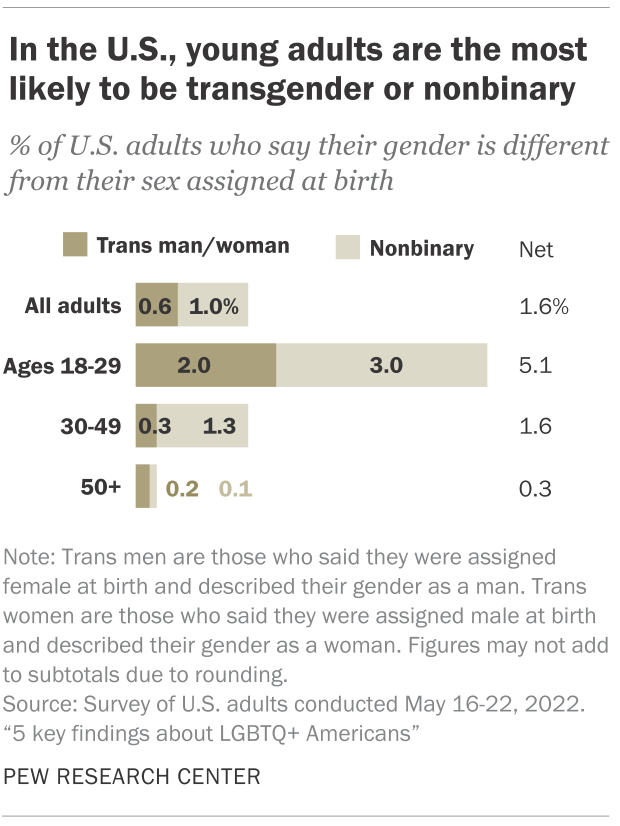

- Gender relates to how people think of themselves. Some people think of themselves as a man or a woman, while others think of themselves another way. They may be nonbinary or use a myriad of other terms such as agender or genderqueer to describe themselves. While overall a small share of U.S. adults are nonbinary – 1%, by our count in 2022 – it’s more commonplace among young adults and in some cultures. Pew Research Center’s current standard question asks about gender, since gender is most directly relevant to our analysis of Americans’ attitudes and experiences.

Identifying whether someone is transgender, that is, whether their gender is different from the sex they were assigned at birth, requires a different approach.

Some surveys simply add “transgender” as a third option to a gender question, alongside “man” and “woman.” However, this approach may underestimate the number of people who are transgender, many of whom might use several of these terms to describe themselves and may prefer to select “man” or “woman” if forced to choose.

Another approach is to ask a yes/no question like, “Do you consider yourself to be transgender?” This should capture people who identify with the term transgender, but not everyone whose gender differs from their sex assigned at birth uses that term to describe themselves.

The generally accepted gold standard for capturing a broad range of transgender individuals uses one question asking about sex assigned at birth and another asking about gender. If the respondent answers the two questions differently – for instance, if they indicate their assigned sex is female but their gender is a man – they would be considered transgender in this definition. This is the approach Pew Research Center took when estimating the share of the population that is transgender or nonbinary. Among other findings, that study found that about 5% of adults under the age of 30 say that their gender is different from their sex assigned at birth.

There are also many facets of sexual orientation to consider:

- Someone’s sexual identity or orientation – whether they are straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual or another identity such as asexual or queer – is the concept that we and many other social science researchers focus on. But measuring sexual identity is not without its complications. More and more people are identifying with terms other than straight, gay, lesbian and bisexual, or rejecting labels altogether. These labels also may not fit well for people who are trans or nonbinary, or for those who are attracted to trans or nonbinary people. But surveys of the general public must balance allowing respondents to see their own identity in the question while also using language that most people will understand.

- Sexual behavior is another facet of sexual orientation, measuring the sex of a respondent’s current or past romantic or sexual partners (if they have had any). This is a critical measurement for many health researchers and demographers, but without a measure of how people self-identify, it may provide an incomplete picture of a person’s sexuality.

This isn’t an exhaustive list of all the facets of gender and sexual orientation that researchers might be interested in. For example, gender expression – how you outwardly express your gender identity, such as with your clothing, hairstyle or what pronouns you use – could be of interest for those who are studying identity.

Depending on the purpose of the survey, researchers may want to use different combinations of these concepts. For example, a researcher studying health outcomes may ask about sex assigned at birth and sexual behavior. For a study about identity and discrimination, questions on gender, transgender identity and sexual orientation could be more appropriate.

Thinking on this topic continues to evolve

Some federal surveys are beginning to measure these concepts and report data on the LGBTQ population and same-sex couples. Perhaps the most critical challenge is that survey research must keep up with the rapidly evolving way that people think about these topics. Terms such as queer, asexual and others are gaining popularity, and some people even reject labels outright. There’s also a growing recognition that many view their gender or sexuality as fluid and the terms that they identify with may change.

The political backlash against efforts to provide more rights and services to transgender and nonbinary individuals may also affect how some respondents react to this question. In particular, concerns about possible discrimination may lead some individuals to be less forthcoming about their sexual and gender identities in surveys.

And finally, another topic ripe for more research is translation of these questions into other languages. While gender and sex questions can be fairly straightforward, a perpetual challenge for U.S. survey researchers is the translation of the sexual orientation question into Spanish. No direct translations of “heterosexual,” “straight” or “gay” exist in Spanish, and commonly used substitutes for these terms can vary from country to country in the Spanish-speaking world.