After more than a decade of studying the spread and impact of digital life in the United States, Pew Research Center has intensified its exploration of the impact of online connectivity among populations in emerging economies – where the prospect of swift and encompassing cultural change propelled by digital devices might be even more dramatic than the effects felt in developed societies.

Surveys conducted in 11 emerging and developing countries across four global regions find that the vast majority of adults in these countries own – or have access to – a mobile phone of some kind.1 And these mobile phones are not simply basic devices with little more than voice and texting capacity: A median of 53% across these nations now have access to a smartphone capable of accessing the internet and running apps.

This report is the first of several reports that will be issued this year based on nationally representative surveys of adults ages 18 and older conducted in 11 countries located in four different regions of the globe: Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia; South Africa and Kenya; India, Vietnam and the Philippines; and Tunisia, Jordan and Lebanon.

These countries were selected for the survey based on a number of criteria. Key goals of the country selection process were to assemble a group of countries that:

- Are middle-income countries as defined by the World Bank.

- Contain a mix of people with different sorts of devices. Many of these countries have notable variation in the share of their populations who have smartphones, more basic phones – or no phones at all.

- Offer country-level diversity and variety. These countries offer a variety of regional, political, economic, social, cultural, population size and geographic conditions.

- Vary in their market conditions. These countries differ in their technological and industry competitiveness, and have a range of “networked readiness” ratings as calculated by the World Economic Forum.

- In many cases have high levels of internal or external migration. Each of these countries exhibits rising levels of urbanization, and most still have substantial rural populations. A special report examining the impact of mobile phones on the migrant experience is also forthcoming.

In concert with this development, social media platforms and messaging apps – most notably, Facebook and WhatsApp – are widely used. Across the surveyed countries, a median of 64% use at least one of seven different social media sites or messaging apps.2 Indeed, smartphones and social media have melded so thoroughly that for many they go hand-in-hand. A median of 91% of smartphone users in these countries also use social media, while a median of 81% of social media users say they own or share a smartphone.

Throughout this report, median percentages are used to help readers see overall patterns. The median is the middle number in a list of figures sorted in ascending or descending order. In a survey of 11 countries, the median result is the sixth figure on a list of country-level findings ranked in order.

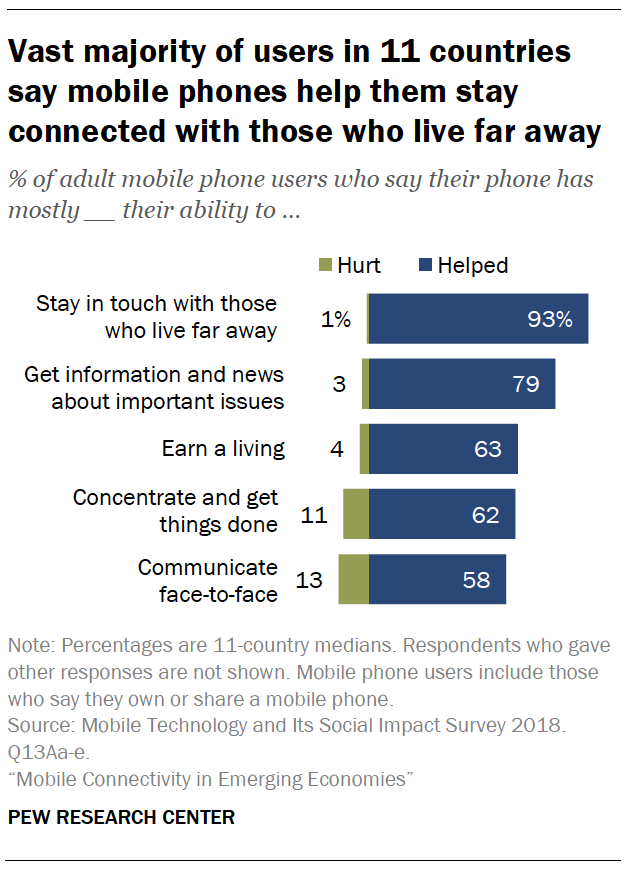

People in these nations say mobile phones have helped them personally in various ways. Among mobile phone users, an 11-country median of 93% say these devices have helped them stay in touch with people who live far away, and a somewhat smaller share (a median of 79%) say they have helped them obtain news and information about important issues. More broadly, majorities of adults in all 11 countries say the internet has had a good impact on education – and majorities in 10 of 11 countries say the same of mobile phones.

Facebook has brought a lot of advantages for our society. However, it has also affected society in a negative way. Just like anything which can be used for both good and bad, social media have brought negatives and positives for people.MAN, 22, PHILIPPINES

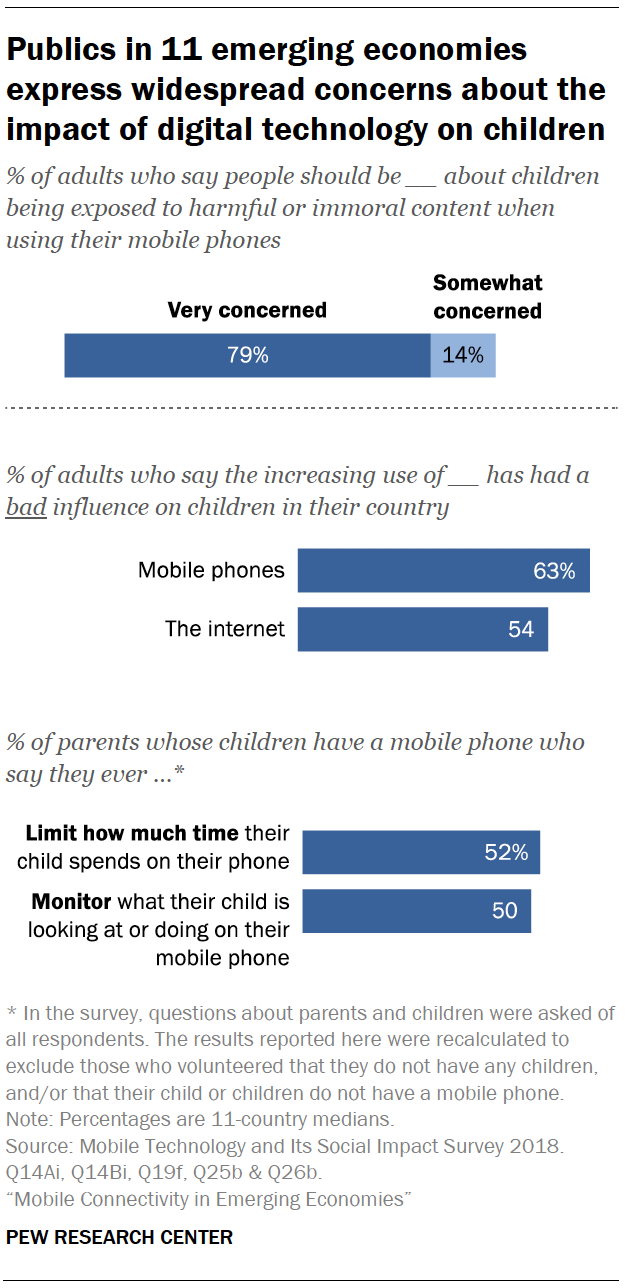

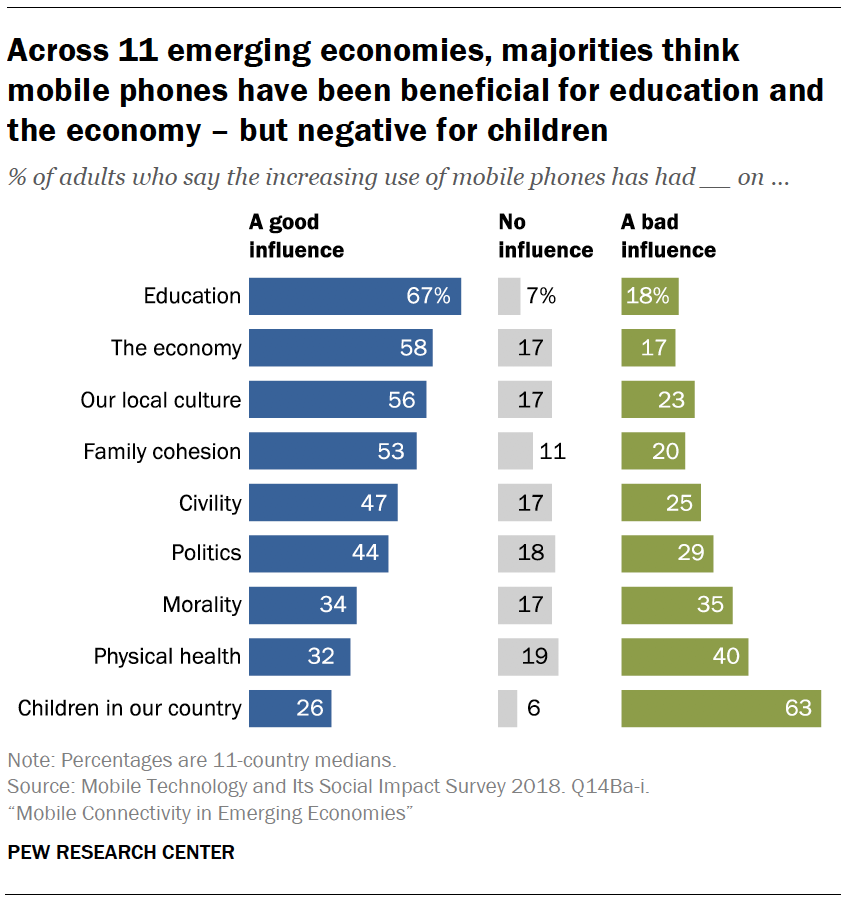

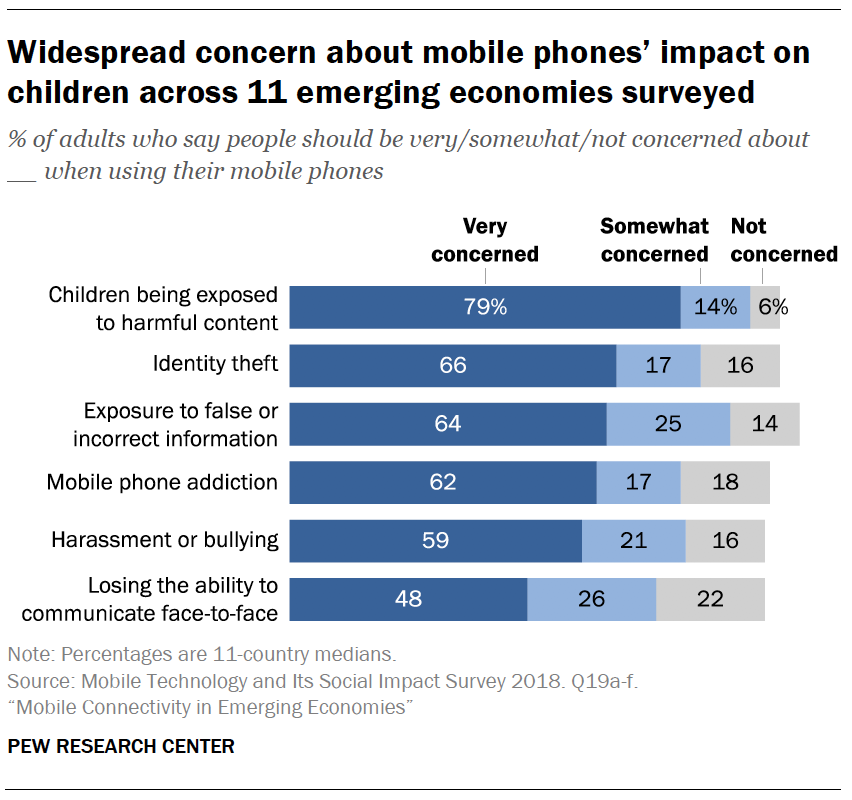

At the same time, smaller shares of adults in these nations say mobile phones and social media have been good for society than say these technologies have been good for them personally. And the challenges that digital life can pose for children are a particularly notable source of concern. Some 79% of adults in these countries say people should be very concerned about children being exposed to harmful or immoral content when using mobile phones, and a median of 63% say mobile phones have had a bad influence on children in their country. They also express mixed opinions about the impact of increased connectivity on physical health and morality.

Some of these tensions between the upsides and downsides of digital life span all 11 countries surveyed. At other times, there are nation-specific elements to people’s views about what these technologies have brought to their lives. For instance, more than half of mobile phone users in five of these countries describe their phone as something they couldn’t live without – but users in six countries are more likely to describe it as something they don’t always need.

These are among the major findings from a new Pew Research Center survey conducted among 28,122 adults in 11 countries from Sept. 7 to Dec. 7, 2018. In addition to the survey, the Center conducted focus groups with diverse groups of participants in Kenya, Mexico, the Philippines and Tunisia in March 2018, and their comments are included throughout the report.

Pew Research Center conducted a series of focus groups to better understand how people think about their own mobile phones and the impact of these devices on their society. Five focus groups were held in each of the following four countries: Kenya, Mexico, the Philippines and Tunisia. Each focus group consisted of 10 adults coming together for an hour and a half for a discussion led by a local, professional moderator using a guide developed by the Center. For more information on how these groups were conducted, see Appendix A.

These groups were primarily used to help shape the survey questions asked in each of the 11 countries. But, throughout the report, we have also included quotations that illustrate some of the major themes that were discussed during the groups. Quotations are chosen to provide context for the survey findings and do not necessarily represent the majority opinion in any particular group or country. Quotations may have been edited for grammar and clarity.

Majorities say mobile phones and social media have mostly been good for them personally, somewhat less so for society

Asked for their overall assessment of the impact of mobile devices and social media platforms on society and their own lives, people in these nations generally are more affirming than not. But within this broadly positive consensus, there are important nuances.

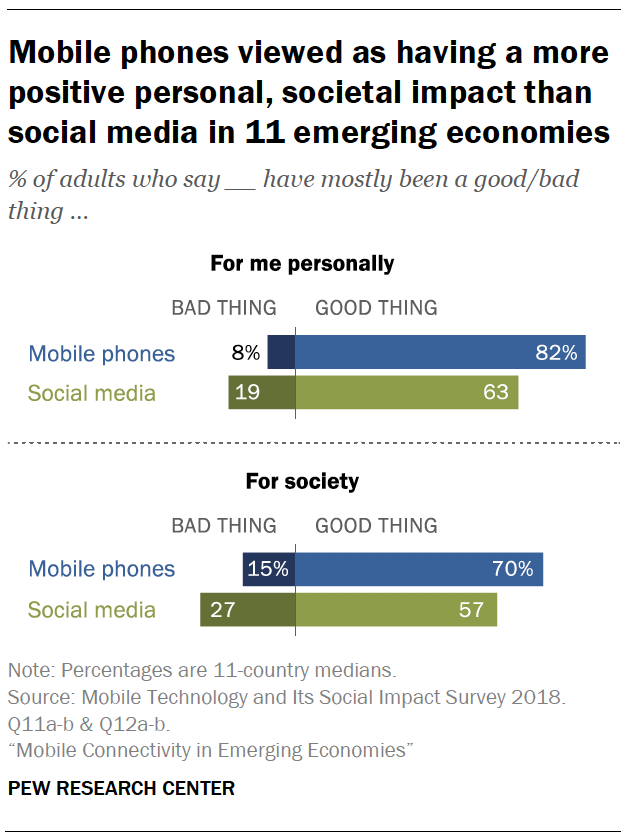

First, at both a personal and societal level publics are generally more likely to say mobile phones have had a mostly good impact than to say the same of social media. A median of 70% of adults across these 11 countries say mobile phones have been a mostly good thing for society, but that share falls to 57% on the question of the impact of social media. Indeed, a median of 27% think social media have been a mostly bad thing for society.

Second, these publics are more likely to say that both mobile phones and social media have been mostly good for them personally than they are to say they have been mostly good for society. As noted above, an 11-country median of 70% say that mobile phones have been mostly good for society. But an even larger share of 82% say mobile phones have been mostly good for them personally. When it comes to social media, users of these sites are generally more likely to proclaim their benefits than non-users. Even among users, people’s views of their personal impact tend to be more positive than their views of their societal impact.

These broad themes tend to occur across the full scope of the countries surveyed. But Kenyans and Vietnamese stand out somewhat for their more positive views of the societal impact of both mobile phones and social media. Conversely, relatively large shares of Venezuelans view the societal impact of these technologies as a negative one.

Many worry that mobile phones are a problem for children; it is common for parents to attempt to curtail and surveil their child’s screen time

While on balance people in these nations express largely positive judgments about the personal and societal impact of technologies, they also express significant concerns over the effects mobile phones and online connectivity might have on young people. Worries that mobile phones might expose children to immoral or harmful content are a key flashpoint in these fears. A median of 79% of adults in these 11 countries – and majorities in all countries surveyed – say people should be very concerned about this. More broadly, a median of 54% say the increasing use of the internet has had a bad influence on children in their country, and a median of 63% say the same about mobile phones.

Coupled with these concerns, many parents say they try to be vigilant about what their children are doing and seeing on their phones.3 Among parents whose children have mobile phones, a median of 50% say they monitor what their children do on their mobile devices. Parents who are themselves smartphone or social media users are more likely than non-users to monitor their child’s phone in this way. Along with monitoring their children’s activities on their mobile devices, a median of 52% of parents whose children have mobile phones have tried to limit the time their children spend with their phones.

Beyond these concerns about the influence of connectivity on children, people’s views of the broader impact of digital technologies on family life are more positive. For instance, the vast majority of mobile phone users (a median of 93% across the 11 countries) say their phone has helped them stay in touch with people who live far away. And although majorities of Lebanese (70%) and Jordanians (62%) feel that mobile phones have had a bad influence on family cohesion, in most other countries surveyed, more say mobile phones have had a good influence in this regard than a bad one.

Publics are divided over the role mobile phones play in their lives

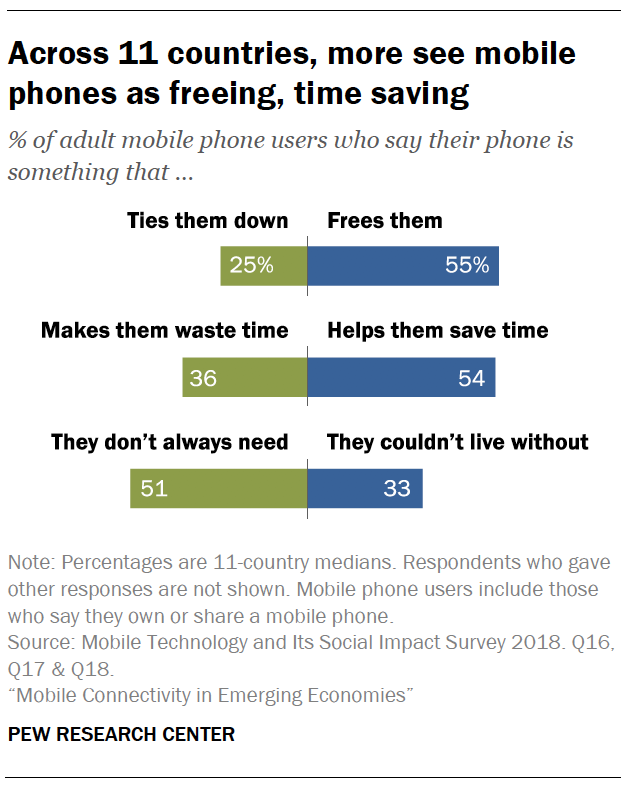

Overall, mobile phone users tend to associate their mobile phones with feelings of freedom. In every country surveyed, a larger share of mobile phone users describe their phone as something that frees them as opposed to something that ties them down.

When it comes to whether their phones help them save time or make them waste time, the largest share of mobile phone users in seven countries describe their phone as something that helps them save time. Still, larger shares of Jordanians and Filipinos describe their phone as something that makes them waste time. And in Lebanon and Mexico, roughly equal shares see their phone as a time saver and time waster.

Across the 11 countries surveyed, mobile phone users fall into two camps about whether their phone is something they don’t always need or something they couldn’t live without. Kenyans, South Africans, Jordanians, Tunisians and Lebanese who use a mobile phone are more likely to say their phone is something they couldn’t live without. But in the six other countries, larger shares say they don’t always need their phone.

Both phone type and demographic differences are at the core of these assessments about the value of mobile phones in users’ lives. For instance, adults ages 50 and older are more likely than those under 30 to view their phone as a time saver, while younger adults are more likely to view it as a time waster – a relationship that persists in most countries even when accounting for age-related differences in smartphone use. And although mobile phone users tend to see their phone as something that frees them, the prevalence of these attitudes varies by device type. For instance, in most countries, smartphone users are more likely than basic or feature phone users to say their phone is something that ties them down rather than something that frees them.

Have you ever gone one day without a phone? You feel like you’re not in this world.MAN, 32, KENYA

Publics in these countries say mobile phones have a beneficial impact on certain aspects of society, but a more negative influence on others

People’s assessments of the specific societal impacts of mobile phones vary depending on the aspect of society in question. Broadly, people in most countries think mobile phones and the internet have had similar impacts on society – possibly because for many their online access comes through a mobile phone.

In most countries, education stands out as the issue where the largest share of adults say the increasing use of the internet and mobile phones has had a good impact. A median of 67% say this about the impact of mobile phones, and a median of 71% about the internet. Public attitudes regarding the influence of the internet on education have grown more positive since 2014 in six of the countries studied here (Jordan, South Africa, Kenya, Vietnam, Lebanon and Mexico), while falling in Tunisia.

Adults in the 11 nations surveyed also view these technologies as having a largely good influence on the economy: A median of 58% say this of mobile phones and 56% say same about the internet. And in seven of the 10 countries for which trends are available, more people today say the increasing use of the internet has had a good influence on their country’s economy than said the same in 2014.4

But digital connectivity is seen in a less positive light when it comes to other issues. In addition to their widespread worries about the impact on children, publics in these countries also express mixed views about increased connectivity’s impact on health. An 11-country median of 40% say mobile phones have had a bad influence on physical health, and 37% say the same of the internet. Majorities of the public in Jordan, Lebanon and Tunisia view these technologies as having a negative influence on health.

Children usually play with gadgets the most and are exposed to radiation and experiencing seizures – that’s what I heard.MAN, 43, PHILIPPINES Also, instead of playing outside, they are busy with gadgets. […] They are no longer able to socialize with other kids.WOMAN, 21, PHILIPPINES

In addition, a median of 35% say that both mobile phones and the internet have had a bad influence on morality. In four countries for which trend data are available (Kenya, Venezuela, Mexico and Colombia), larger shares of the public say the internet has had a good influence on morality than was true four years ago. But in Jordan and Lebanon, the shares saying this have declined since 2014.

When people consider issues such as the impact of digital tools on local culture, civility, family cohesion and politics, the overall balance of public sentiment leans positive. But notable minorities – ranging from a median of 20% in the case of family cohesion to a median of 29% in the case of politics – say mobile phones have had a negative impact on these facets of society.

Moreover, public opinion across these 11 countries has diverged in recent years when it comes to the internet’s impact on politics. Compared with surveys conducted in 2014, larger shares of Mexicans, South Africans, Venezuelans, Kenyans and Colombians now say increasing use of the internet has had a positive impact on politics. But Tunisians, Lebanese and Jordanians are now less likely to say this compared with 2014.

Despite wide-ranging worries about the problems mobile phones invite, personal benefits are still widely recognized

In addition to their concerns about the impact of mobile phones on children, majorities across the 11 countries surveyed also say people should also be very worried about issues such as identity theft (an 11-country median of 66% say people should be very concerned about this), exposure to false information (64%), mobile phone addiction (62%) and harassment or bullying (59%) when using their mobile phones. Fewer are very concerned about the risk that people might lose the ability to communicate face-to-face due to mobile phone use (48%).

Yet these broader concerns often coexist with perceived benefits to users. For instance, despite widespread concerns that mobile phones might expose people to false or inaccurate information, a sizable majority of mobile phone users (79%) say their own phone has helped their ability to get news and information about important issues. Similarly, a median of 58% of mobile phone users say their devices have helped their ability to communicate face-to-face – even as a median of 48% of adults in these countries say people should be very worried about mobile phones’ effects on face-to-face communication.

Other key findings relating to the adoption and use of digital technology in these countries include:

- Majorities in each country own their mobile phone, and sharing a phone with someone else is relatively rare. A median of just 7% of adults in these countries share a mobile phone, ranging from a low of 1% of adults in Vietnam to a high of 17% in Venezuela.

- Smartphone use is higher among younger adults and those with higher education levels.5 Lebanon and Jordan are the only countries in the survey in which a majority of adults ages 50 and older – as well as a majority of those with less than a secondary education – are smartphone users.

- Home computer and tablet access is relatively rare in these countries: A median of 34% have access to either kind of device. And a median of 27% of adults in these countries say they do not have a tablet or computer at home but do have a smartphone, ranging from a low of 18% in Venezuela to a high of 50% in Jordan.

- By a substantial margin, Facebook (used by a median of 62% of adults in these countries) and WhatsApp (used by a median of 47%) are the two most commonly used social media or messaging platforms out of the seven included in the survey. To the extent that adults use only one of these platforms, in every country that platform is either Facebook or WhatsApp.

- Some social media platforms or messaging apps are more popular in some countries than in others. For example, about one-third of Lebanese adults (34%) use the photo-sharing site Instagram. The messaging app Viber is more popular in Lebanon and Tunisia – where about one-in-five adults report using it – than elsewhere, while Jordanians stand out for their use of the photo-messaging app Snapchat (24%).