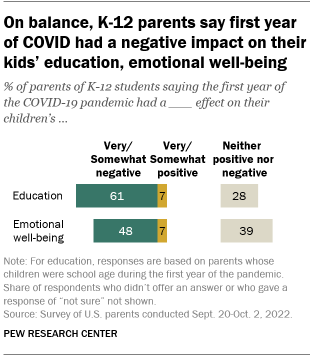

Recent findings from the National Assessment of Educational Progress add to mounting evidence that the transition to remote learning in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic created gaps in learning that had a lasting impact on K-12 students in the United States. These findings are echoed in the views of many K-12 parents: About six-in-ten (61%) say the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s education. Just 7% say it had a positive effect, while 28% say it had neither a positive nor negative effect.

Among parents who say the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s education, more than four-in-ten (44%) say this is still the case today, while 56% say the impact was only temporary, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of U.S. parents.

The early stages of the pandemic also presented emotional challenges for children and teens. About half of parents (48%) say that the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s emotional well-being, while 7% say it had a positive effect and 39% say the impact was neither positive nor negative. Among parents who say there was a negative impact in the first year, most (74%) say their children’s emotional well-being has gotten better, while 8% say it’s gotten worse and 18% say things have stayed about the same.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to study how parents of K-12 students assess the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on their children’s education and emotional well-being. To do this, we surveyed 3,757 U.S. parents with at least one child younger than 18 (including 3,251 who have a child in a K-12 school) from Sept. 20 to Oct. 2, 2022. Because parents with multiple children in K-12 schools may have different answers to these questions depending on the child or the school they attend, these parents were randomly assigned to think about their youngest or oldest child who is in K-12 when answering these questions. The data was weighted to account for the probability of being assigned to a child in elementary, middle or high school and is representative of all parents of students at each of these stages.

Most parents who took part are members of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This survey also included an oversample of Black, Hispanic and Asian parents from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel, another probability-based online survey web panel recruited primarily through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Address-based sampling ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology.

Related: Parents Differ Sharply by Party Over What Their K-12 Children Should Learn in School

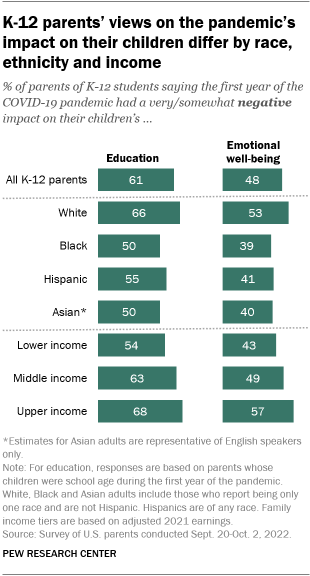

Parents’ views on the effect of the first year of the pandemic on their children’s education differ significantly by race and ethnicity. While studies show that learning loss was more severe for Black and Hispanic students, White parents (66%) are more likely than Black (50%), Hispanic (55%) and Asian parents (50%) to say that the first year of the pandemic had a negative impact on their children’s education.

Income is another factor: A greater share of upper-income parents (68%) say their children’s education was negatively affected, compared with middle- and lower-income parents (63% and 54%, respectively).

The patterns are similar when it comes to the impact of the pandemic on children’s emotional well-being. White parents (53%) are more likely than Black (39%), Hispanic (41%) and Asian parents (40%) to say the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s emotional well-being. And a higher share of upper-income parents (57%) than middle- or lower-income parents say the same (49% and 43%, respectively).

Parents’ views on the emotional impact of the first year of the pandemic also differ by the age of their children. Parents of high school and middle school students (57% and 50%, respectively) are more likely than parents of elementary school students (43%) to say the emotional effect was negative.

When asked whether the effects of the first year of the pandemic are still a factor for their children today, the results are mixed. Among parents who say the first year of the pandemic had a negative impact on their children’s education, a majority (56%) say the negative effect was only temporary. Still, 44% say it is still having an effect today.

These assessments don’t differ substantially across key demographic groups, but there are differences by the type of school children attend. Parents who were answering about a child in a public school were more likely than those answering about a child in a private school to say there is still a negative effect on their child’s education today (45% vs. 36%).

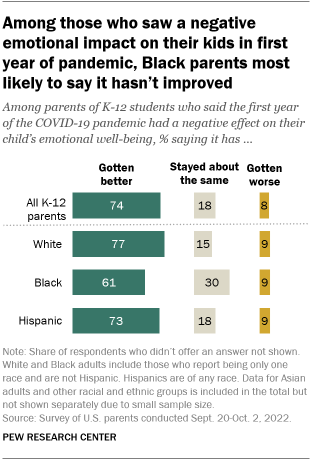

When it comes to the emotional impact of the pandemic, most parents who say there was a negative effect in the first year say things are better now (74%). But these attitudes differ by race and ethnicity.

Among parents who say the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect, White (77%) and Hispanic parents (73%) are more likely than Black parents (61%) to say their children’s emotional well-being has gotten better. Roughly four-in-ten Black parents say the negative effects of the first year of the pandemic have persisted or gotten worse. This compares with about a quarter of White and Hispanic parents. (There are too few Asian parents to analyze separately on this question.)

Upper-income parents who say the first year of the pandemic had a negative effect on their children’s emotional well-being are more likely than middle- or lower-income parents to say their children are doing better now in this regard (81% vs. 73% and 70%, respectively).

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology.