Joe Biden’s selection of Sen. Kamala Harris of California as his running mate in this year’s presidential election has sparked a conversation about multiracial identity in the United States. Harris, the daughter of immigrants from Jamaica and India, is among a relatively small but growing group of Americans with a multiracial background.

See also: Key facts about Black immigrants in the U.S.; Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S.

Some 6.2 million U.S. adults – or 2.4% of the country’s adult population – report being two or more races, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of 2018 U.S. Census Bureau data. Of these Americans, 22% are White and American Indian, 21% are Black and White, 20% are White and Asian American, 4% are Black and American Indian and 2% are Black and Asian American. About three-in-ten (31%) are some other combination, including 9% who select three or more races. The 2000 census was the first time Americans were able to choose more than one race to describe themselves, allowing for an estimate of the nation’s multiracial population.

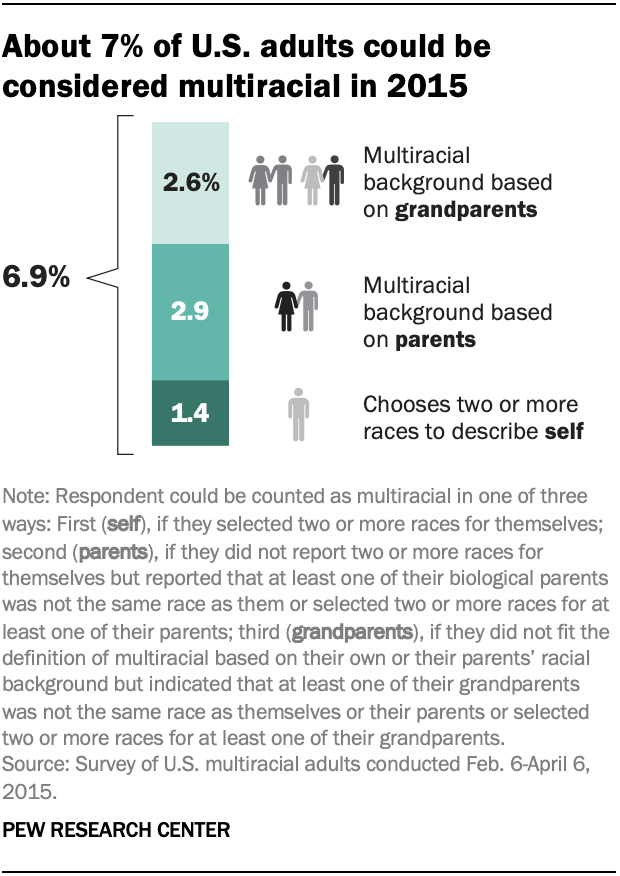

In a 2015 study that used a broader definition of the term – one that took into account how adults described their own race as well as the racial background of their parents and grandparents – Pew Research Center estimated that 6.9% of the U.S. adult population could be considered multiracial. The 2015 study also explored the attitudes and experiences of these adults, revealing the complexities of multiracial identity. Here are five key findings from that report:

In 2015, Pew Research Center conducted a study to examine the attitudes, experiences and demographics of multiracial Americans. We surveyed 1,555 multiracial U.S. adults from Feb. 6-April 6, 2015. The survey was conducted online in English and Spanish. Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology.

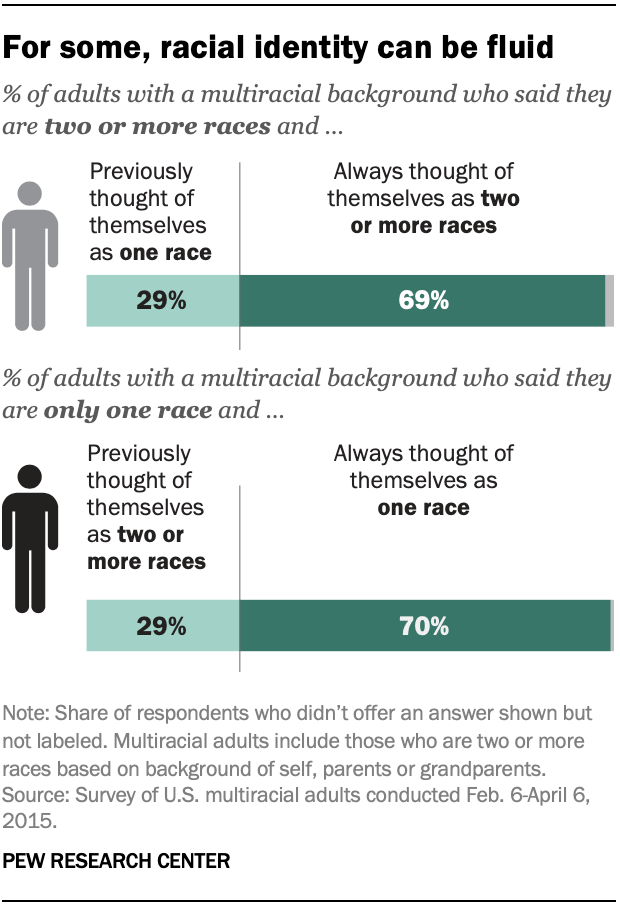

Racial identity can change over the course of one’s life. While 69% of Americans who reported more than one race for themselves in the 2015 survey said they always thought of themselves as two or more races, about three-in-ten (29%) said there was a time when they thought of themselves as only one race. Similarly, among adults who selected only one race for themselves but had a multiracial family background, 29% said they once thought of themselves as being two or more races.

About one-in-five adults with a multiracial background (21%) said they have felt pressure from friends, family or society in general to choose one of the races in their background over another. Multiracial adults with a Black background were among the most likely to say they had felt such pressure to identify as single race.

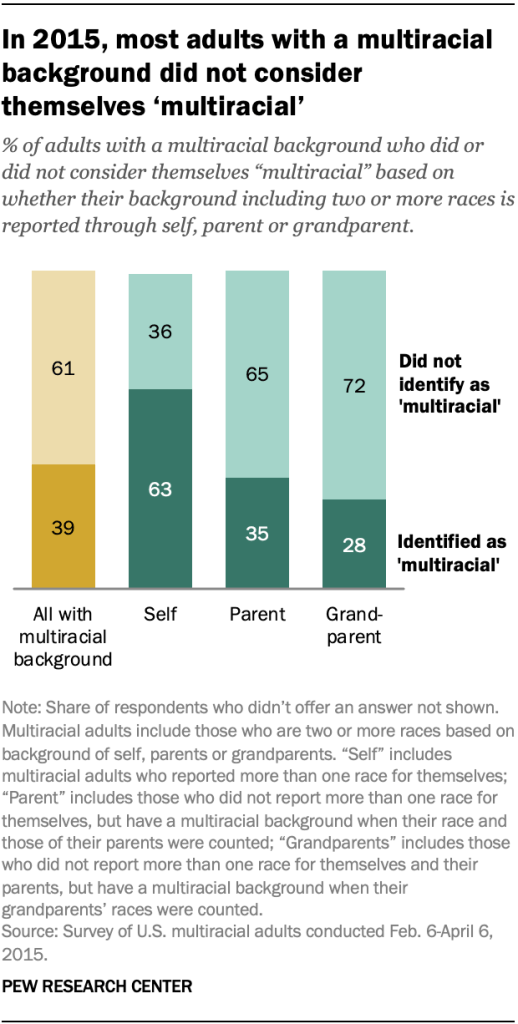

Most adults with a background that includes more than one race do not consider themselves “multiracial.” In 2015, 61% of those who reported two or more races for themselves, their parents or their grandparents said they didn’t consider themselves to be multiracial. This was especially the case for those who didn’t select two or more races for themselves but who were considered to have a multiracial background based on their parents’ or grandparents’ races. Among those who chose two or more categories when asked about their own race, 36% said they didn’t consider themselves multiracial, suggesting that the boxes people check don’t always align with how they identify.

When asked why they didn’t consider themselves to be multiracial, 47% of those with multiple races in their background cited their family upbringing and/or their physical appearance. (Respondents were allowed to give multiple answers.) About four-in-ten (39%) said they closely identified with one race, and 34% said they never knew their family member or ancestor who was a different race.

Among the 36% of adults who reported two or more categories when asked about their own race but who did not identify as multiracial, 64% said the fact that they “look like one race” was a reason why they didn’t identify that way; 54% said they were raised as only one race, 45% said they closely identify as one race and 33% said they never knew their family member or ancestor who was a different race.

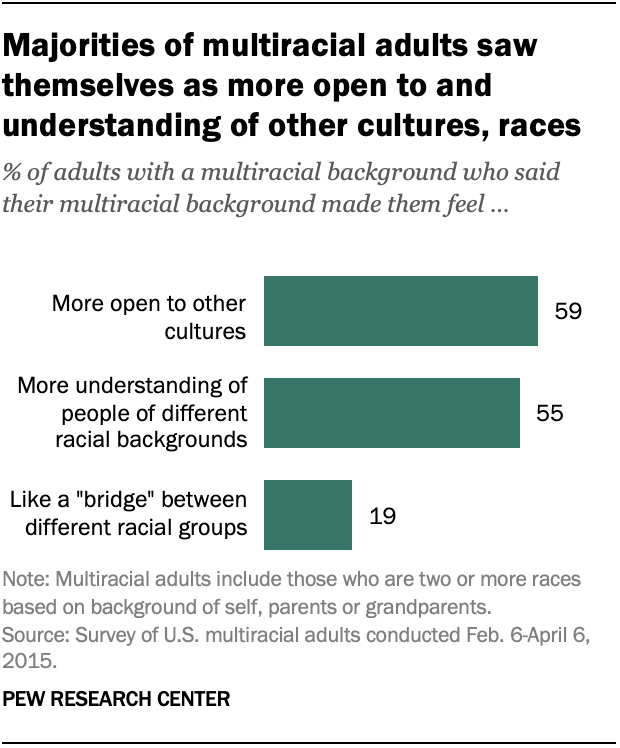

Multiracial adults see themselves as more open to other cultures and more understanding of people of different backgrounds. Around six-in-ten multiracial Americans (59%) said their multiracial background has made them more open to cultures other than their own, and 55% felt that they were more understanding of people of different racial backgrounds. Still, relatively few (19%) said they had felt like they were a go-between or “bridge” between different racial groups.

When it comes to how others see them, a quarter of multiracial adults said people are often or sometimes confused about their racial background. Of those who said this, 62% reported having felt annoyed often or sometimes because someone had made assumptions about their race.

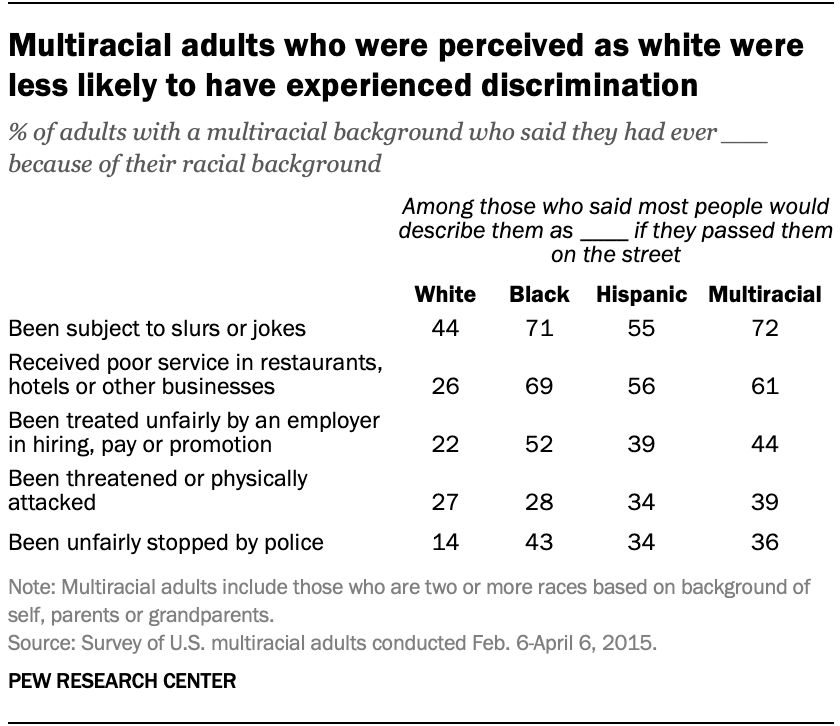

For multiracial adults, experiences with discrimination are often tied to racial perceptions. For example, in 2015, about seven-in-ten multiracial adults who said most people who passed them on the street would describe them as Black (71%) or multiracial (72%) said they have been subjected to slurs or jokes because of their racial background, compared with 55% among those who said most people would describe them as Hispanic and 44% among those who said most people would describe them as White. (The number of people who said most people would describe them as Asian or Asian American, American Indian, or Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander was too small to analyze.)

Multiracial adults who said most people would describe them as White if they passed them on the street were also the least likely to say they had received poor service in restaurants, hotels and other businesses; had been treated unfairly by an employer in hiring, pay or promotion; or had been unfairly stopped by police because of their racial background.

In some instances, experiences with racial discrimination among those who said most people perceived them to be a certain race mirrored those of single-race adults of that race. For example, multiracial adults who said most people would think they were Black were about as likely as single-race Black adults to say they had been unfairly stopped by police or that they had been treated unfairly by an employer. Similarly, multiracial adults who were perceived as White reported facing discrimination at rates similar to those of single-race White adults.

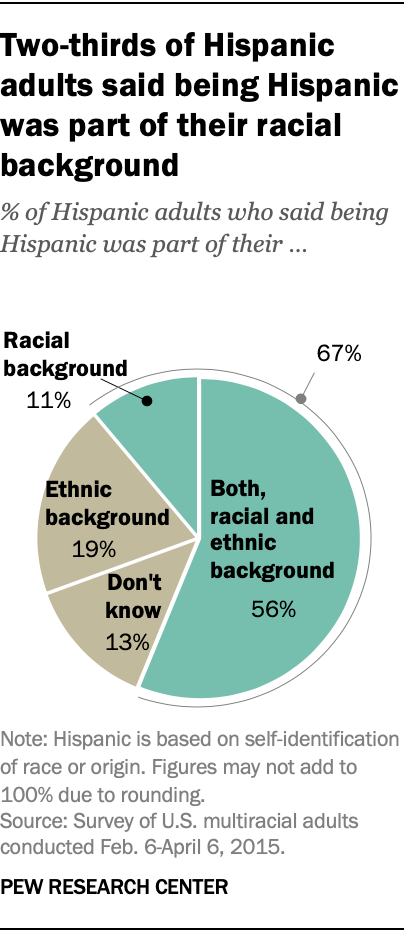

Most Hispanic adults see being Hispanic as part of their racial background. While being Hispanic is described on census survey forms as an ethnic origin and not a race, two-thirds of Hispanic adults said in the 2015 survey that being Hispanic was part of their racial background, including 11% who described it only as their race and 56% who said it was part of both their racial and ethnic background; 19% said being Hispanic was part of their ethnic background only.

Among Hispanic adults who reported two or more racial categories (based on the census definition), 30% said most people would think they were White if they passed them on the street, while 24% said most people would see them as Hispanic, 17% as multiracial, 10% as Black and 4% as Indigenous. But about half of multiracial Hispanics who consider being Hispanic part of their racial background and who chose one census race (48%) said most people would think they were Hispanic if they passed them on the street.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology.