Sermons are a major part of many churchgoers’ religious experiences. But there are differences by religious tradition in how satisfied churchgoers are with what they hear from the pulpit – as well as in the length and content of those sermons, according to two recent Pew Research Center studies.

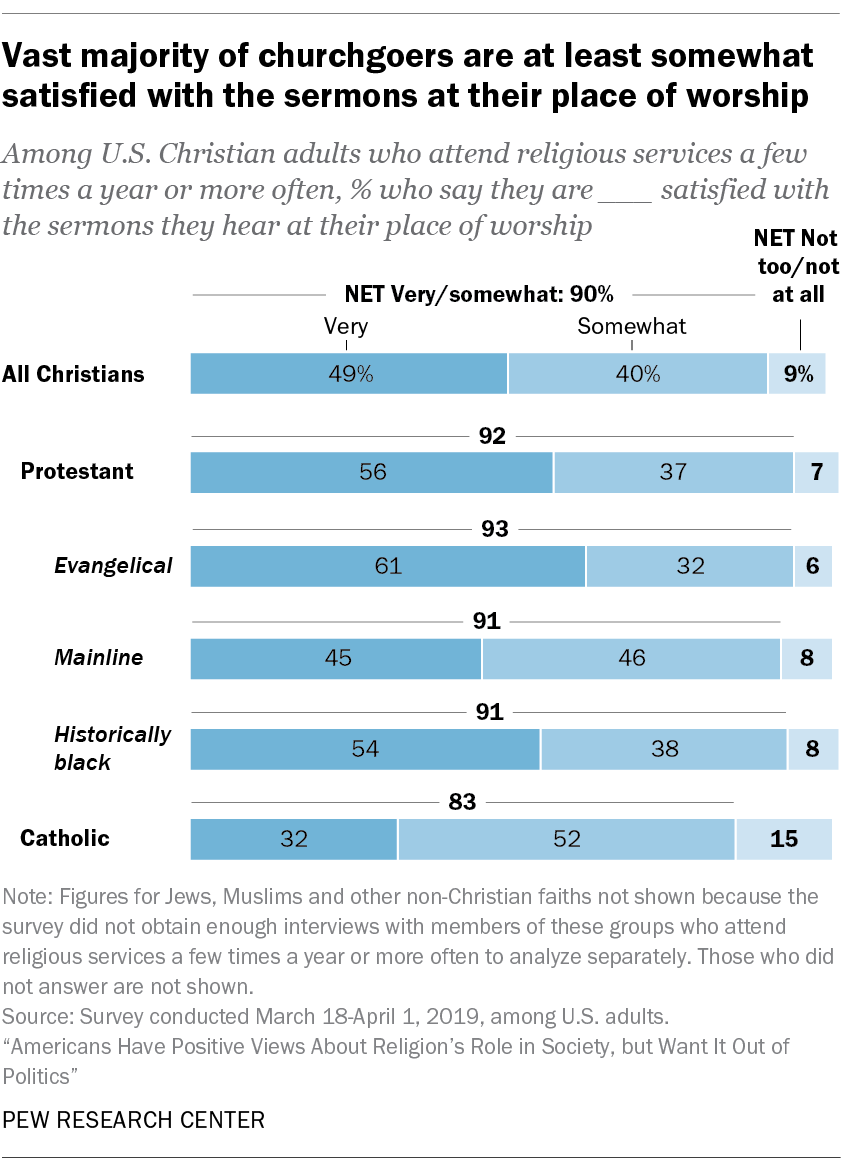

An opinion survey of 6,364 U.S. adults conducted in 2019 found that 90% of Christians who attend worship services at least a few times a year are satisfied with the sermons they hear, though Protestants are somewhat more satisfied than Catholics.

Six-in-ten evangelical Protestants (61%) say they are “very satisfied” with the sermons they hear, almost twice as many as those who say they’re “somewhat satisfied” (32%). Among Catholics, only about a third (32%) say they’re “very satisfied,” while roughly half (52%) say they are “somewhat satisfied.” Catholics also have a higher share of respondents who say they’re “not too” or “not at all” satisfied (15% vs. 7% for Protestants).

How we did this

For the survey component of this post, we polled 6,364 U.S. adults from March 18 to April 1, 2019. The findings were originally published in the report “Americans Have Positive Views About Religion’s Role in Society, but Want It Out of Politics.” The data used in this post comes from a subgroup of respondents who identify as Christian and who say they attend church services a few times a year or more often. Everyone who took part in the survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. Recruiting our panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling).

To further ensure that each survey reflects a balanced cross-section of the nation, the data is weighted to match the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and its methodology.

For the computational findings presented in this post, we analyzed the length and content of 49,719 sermons delivered at 6,431 U.S. congregations between April 7 and June 1, 2019. The results were originally published in the report “The Digital Pulpit: A Nationwide Analysis of Online Sermons.” Pew Research Center identified these sermons using web scraping, a technique that allows researchers to collect information from web pages. The churches were found via the Google Places application programming interface (API), a tool that provides information about establishments, geographic locations or points of interest listed on Google Maps. For more information, see the report’s methodology.

Though it is unclear from the survey why churchgoers’ satisfaction in sermons differ, sermons vary in length and content from one religious tradition to another, according to a separate Pew Research Center study based on a computational analysis of nearly 50,000 sermons livestreamed or shared by more than 6,000 U.S. churches in 2019. (The results of the study are not representative of all U.S. churches: The congregations that shared these sermons tend to be larger and more urban than U.S. congregations overall, and even these churches may not share all their sermons online.)

Catholic sermons are the shortest, at a median of just 14 minutes, compared with 25 minutes for mainline Protestant sermons and 39 minutes for evangelical Protestant sermons, according to the study. Historically black Protestant churches have the longest sermons by far: A median of 54 minutes, more than triple the length of the median Catholic homily posted online during the study period.

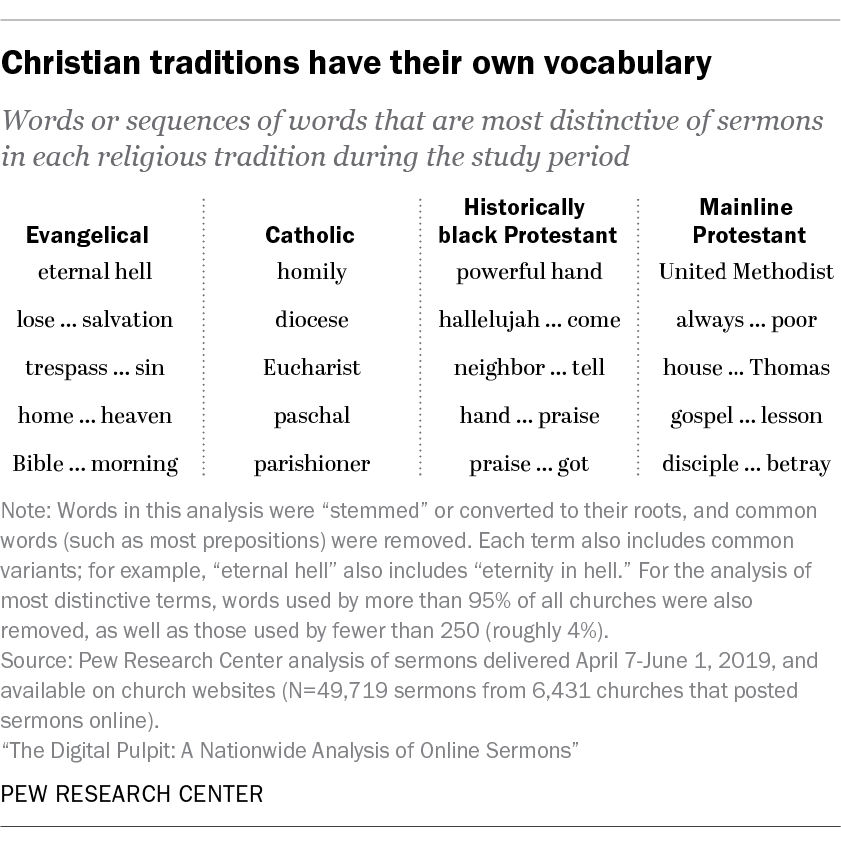

While certain words appear in sermons across all of the Christian traditions in the study, each group uses certain words or phrases more often than other groups. Catholic priests, for example, are 21 times as likely as those in other churches to use the word “homily” and 15 times as likely to use “Eucharist” (both of these are elements of a Catholic service).

Evangelical sermons stand out for using the phrase “eternal hell” or variants like “eternity in hell” – though such phrases are rarely used even among evangelicals. Only one-in-ten evangelical congregations in the dataset heard “eternal hell” even once during the study period.

Some findings may be influenced by the computational study’s timing, which included Easter Sunday and some of Lent, or by calendars such as the common lectionary, which many faith traditions use to pick the Bible passages for their weekly readings.

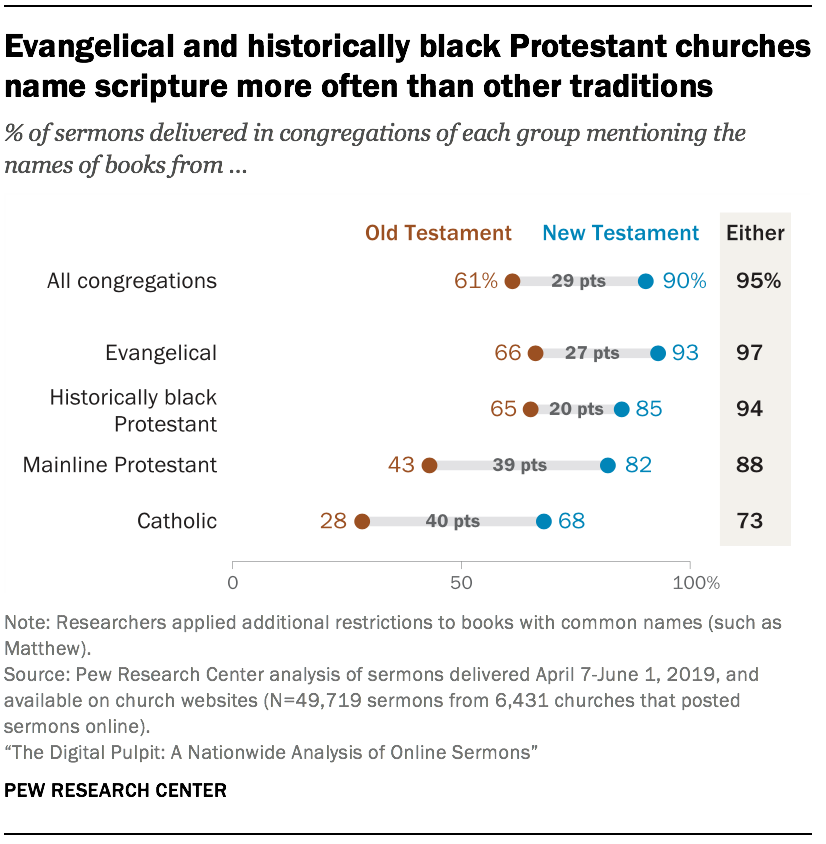

Meanwhile, clergy in the U.S. also differ in how frequently they cite books of the New and Old Testaments – or any scripture at all. Pastors in evangelical congregations are the most likely to reference at least one book of the Bible: 97% of evangelical sermons do so, compared with 94% of historically black Protestant sermons, 88% of mainline Protestant sermons and 73% of Catholic homilies. However, it’s worth noting that many religious traditions include Bible readings in every service, even if they are not mentioned in the sermon or homily that they share online.

Pastors in each of the four faith groups evaluated are more likely to mention the New Testament than the Old Testament. At least one book from the New Testament appears in 90% of sermons, while a book of the Old Testament is cited in 61% of sermons. Mainline Protestant and Catholic sermons cite less scripture overall, but their sermons exhibit the largest gaps between references to the New and Old Testaments.