More people around the world are dissatisfied than satisfied with the way democracy is working in their country, according to a new Pew Research Center report based on a survey of 27 countries conducted in spring 2018.

People who are dissatisfied with democracy in their country are less likely to feel that economic conditions in their country are good, that the financial situation of average people has improved over the past 20 years, and that key democratic norms are being respected, the study finds. Notably, however, dissatisfaction with democracy has little relationship to external assessments of how wealthy or democratic a given country actually is, based on measures from the World Bank, Freedom House, the Economist Intelligence Unit and the Electoral Integrity Project.

Below are four charts that look at dissatisfaction with democracy in more detail:

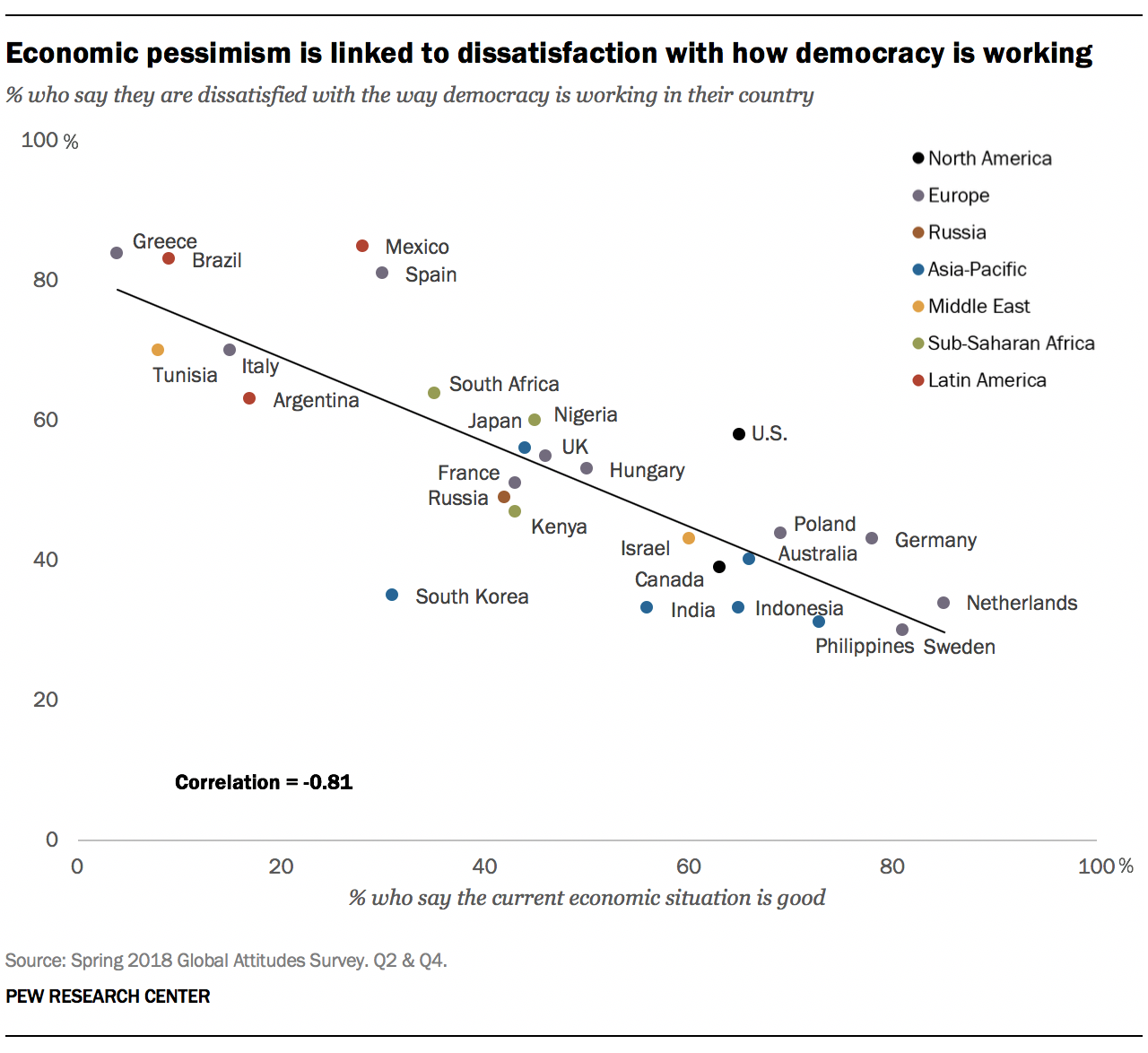

Dissatisfaction with democracy is not related to the overall wealth of a country, but it is strongly related to pessimistic views of the current economic situation. This is the case whether wealth is measured as gross domestic product or as GDP per capita. For example, 9% of Brazilians think their economic situation is good, and 83% are dissatisfied with the way democracy is working in their country. Swedes, on the other hand, have a much rosier outlook on both their economy and democracy: 81% think their country’s economic situation is good, and only about a third (30%) say they are dissatisfied with democracy.

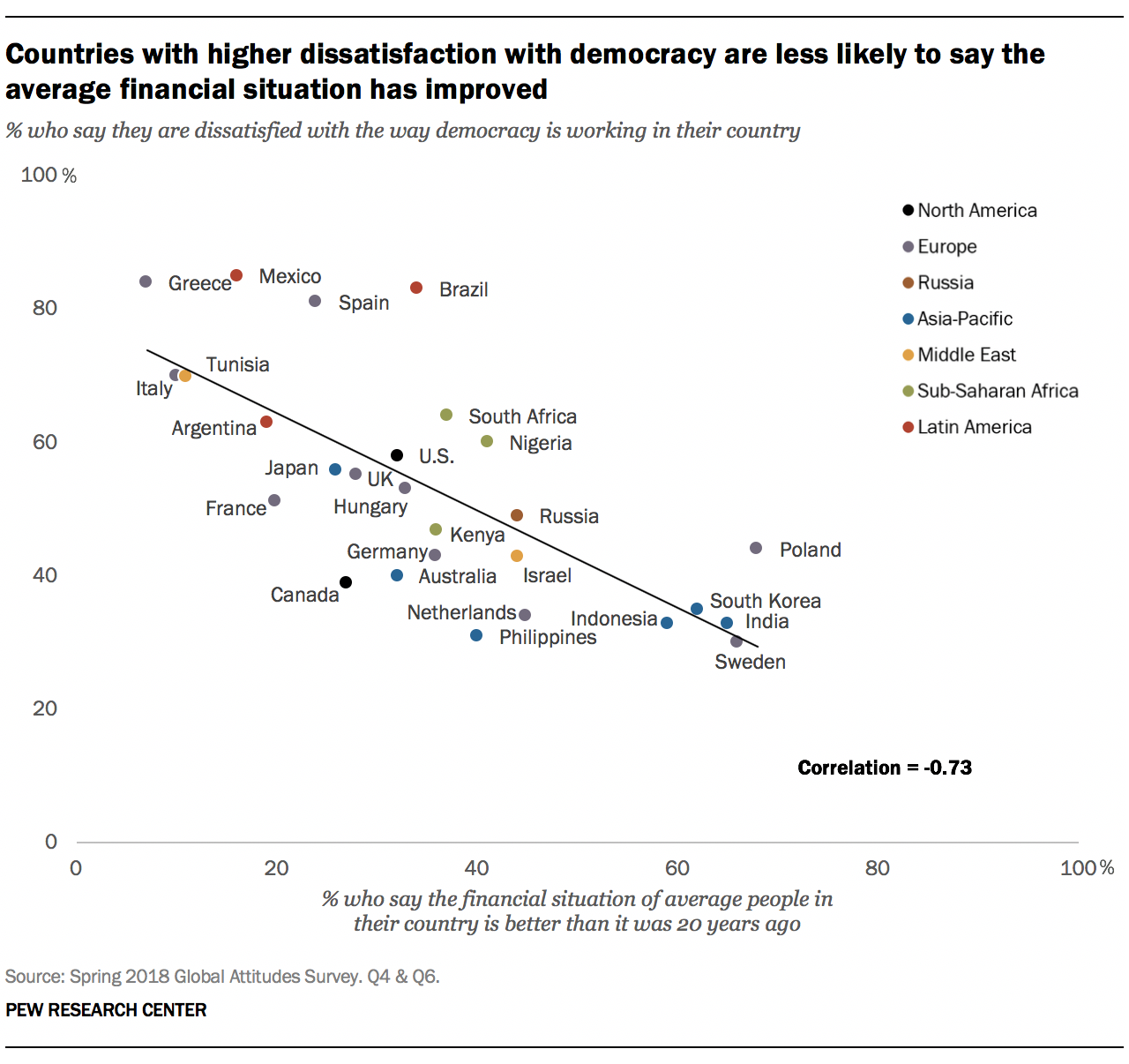

People’s assessments of how the average person’s financial situation has changed over the past 20 years are related to dissatisfaction with democracy. In most of the countries surveyed, minorities believe that the average person’s financial situation has improved compared with 20 years ago. This pessimism is strongly related to how people feel about democratic performance. For instance, in Greece, where 7% say the financial situation of average people has gotten better, 84% say they are dissatisfied with how democracy is operating in their country. In contrast, in India, 65% believe the financial situation has improved and just a third are dissatisfied with democracy.

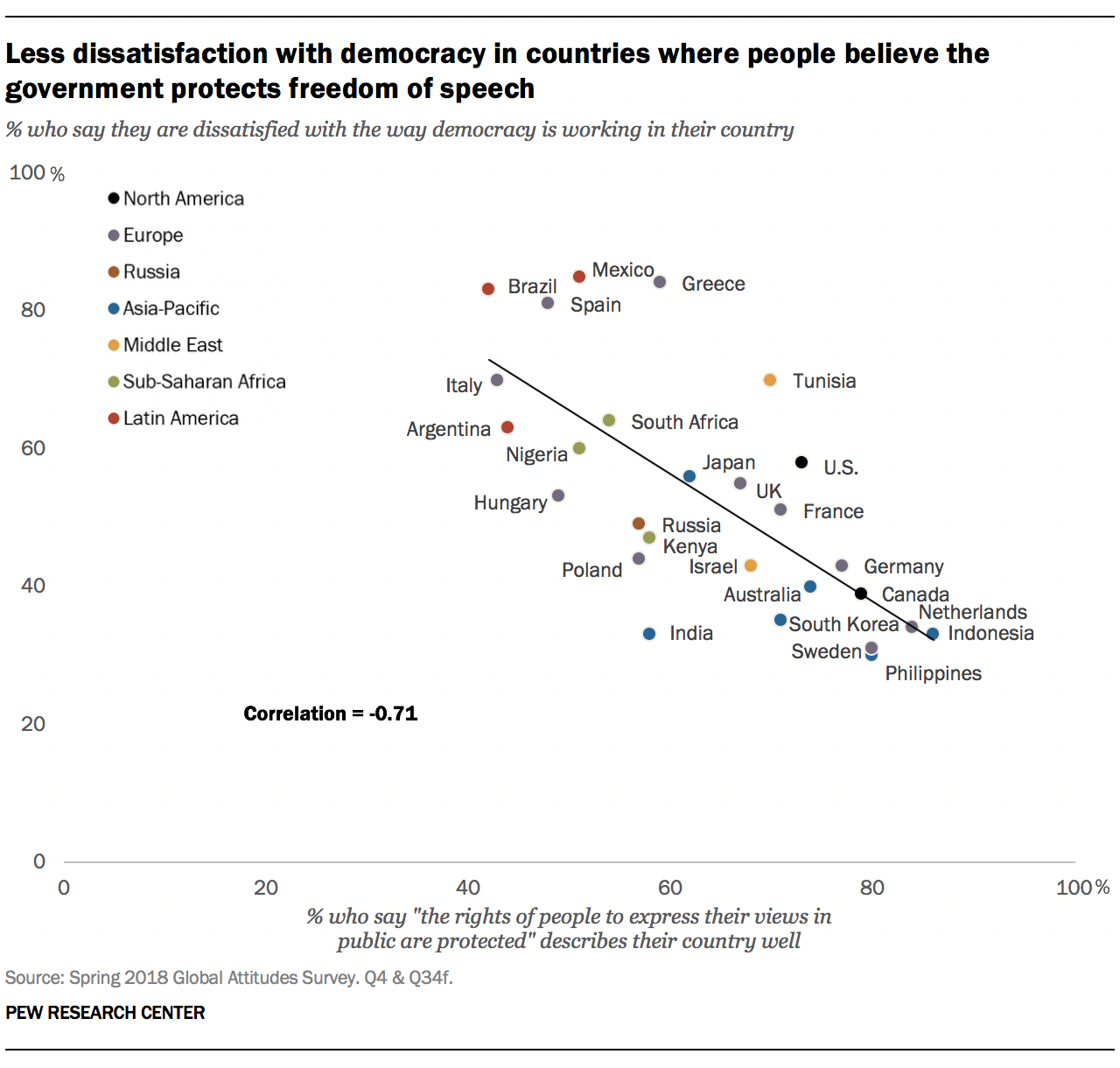

The view that a country protects freedom of speech informs how people feel democracy is working in their country. Perceptions of whether a country protects free speech are crucial in explaining dissatisfaction with democracy: People who say freedom of expression is protected in their country are less dissatisfied with democracy. However, there’s no relationship between dissatisfaction with democracy or the perception that freedom of speech is protected and measures of whether a country protects civil liberties, such as those compiled by Freedom House. Take Spain: The country receives a top score for protections of these rights, but only around half of Spanish adults (48%) believe their country protects their rights to free speech.

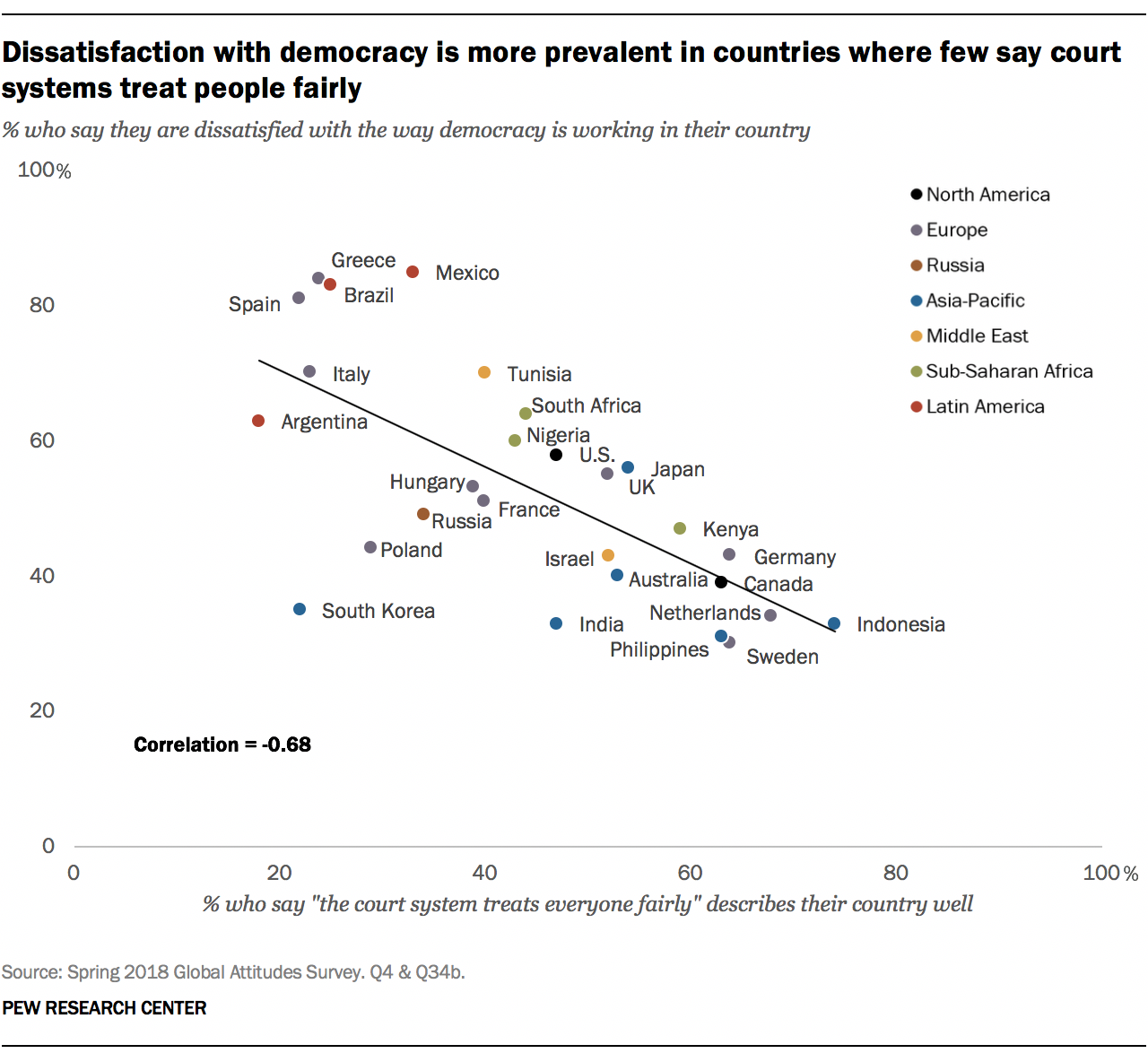

A sense that courts are fair – even if experts say they’re not – shapes how people feel about democracy in their country. Whether people believe their country’s court system treats everyone fairly plays a role in how they think democracy is performing in their country. In Italy, about a quarter of adults (23%) say that courts treat people fairly, and seven-in-ten are dissatisfied with democracy. Conversely, about three-quarters of Indonesians (74%) say courts treat everyone fairly, and only a third are dissatisfied with democracy.

As is the case in views of free speech, there’s little relationship between dissatisfaction with democracy or the perception that a country’s courts treat everyone equally and outside determinations about whether that country has an equitable justice system. Take Spain as an example again: 22% of Spaniards say the nation’s court system treats everyone fairly, despite the fact that the country is classified by V-Dem as having equality before the law.