Despite double-digit percentage decreases in U.S. violent and property crime rates since 2008, most voters say crime has gotten worse during that span, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. The disconnect is nothing new, though: Americans’ perceptions of crime are often at odds with the data.

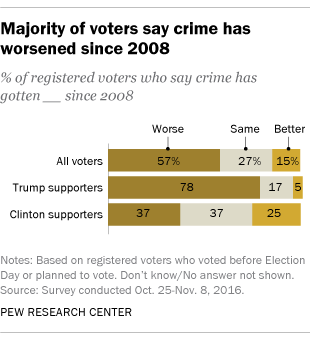

Leading up to Election Day, a majority (57%) of those who had voted or planned to vote said crime has gotten worse in this country since 2008. Almost eight-in-ten voters who supported President-elect Donald Trump (78%) said this, as did 37% of backers of Democrat Hillary Clinton. Just 5% of pro-Trump voters and a quarter of Clinton supporters said crime has gotten better since 2008, according to the survey of 3,788 adults conducted Oct. 25-Nov. 8.

Official government crime statistics paint a strikingly different picture. Between 2008 and 2015 (the most recent year for which data are available), U.S. violent crime and property crime rates fell 19% and 23%, respectively, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, which tallies serious crimes reported to police in more than 18,000 jurisdictions around the nation.

Another Justice Department agency, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, produces its own annual crime report, based on a survey of more than 90,000 households that counts crimes that aren’t reported to police in addition to those that are. BJS data show that violent crime and property crime rates fell 26% and 22%, respectively, between 2008 and 2015 (again, the most recent year available).

So what explains the gap between perceptions of crime and the data? For one thing, official government crime statistics lag behind the times. The FBI and BJS didn’t publish their crime reports for 2015 until fall of this year, meaning they don’t capture recent changes in crime.

Chicago and other large U.S. cities have had well-documented problems with violent crime in 2016 that may have contributed to public perceptions, and a preliminary analysis published by the Brennan Center for Justice in September projects that by year’s end the violent crime rate will have risen nearly 6% from 2015 levels in the nation’s 30 largest cities (including a 13% rise in the murder rate). But even if those trends materialize, the Brennan report cautions that the violent crime rate “remains near the bottom of the nation’s 30-year downward trend.”

Campaign season also may have amplified some voters’ perceptions of rising crime. Trump, in particular, made crime a central focus of his successful campaign for the White House. Citing the recent increases in violent crime in some big cities, he warned at the Republican National Convention that “decades of progress made in bringing down crime are now being reversed.”

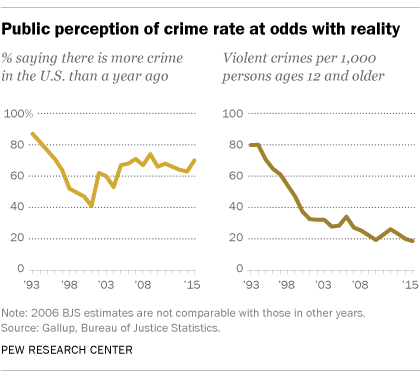

But perhaps the best context for understanding the conflict between voters’ perceptions of crime and the data is that voters are usually more likely to say crime is up than down, regardless of what official statistics show.

Since 1989, Gallup has asked respondents whether they think there is more or less crime in the U.S., compared with the year before. In 21 of the 22 years Gallup asked this question, a larger share of respondents said there was more crime. Only in 2001 did roughly equal shares of respondents say there was more crime (41%) versus less (43%). (Gallup has also asked Americans since 1972 whether there was more or less crime in their area; in all but six years, a substantially larger share said crime was up.)

These polling trends stand in sharp contrast to the long-term crime trends reported by the FBI and BJS. Both agencies have documented big decreases in violent and property crime rates since the early 1990s, when U.S. crime rates reached their peak. The BJS data, for instance, show that violent and property crime levels in 2015 were 77% and 69% below their 1993 levels, respectively.