Roughly 34 million lawful immigrants live in the United States. Many live and work in the country after receiving lawful permanent residence (also known as a green card), while others receive temporary visas available to students and workers. In addition, roughly 1 million unauthorized immigrants have temporary permission to live and work in the U.S. through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status programs.

Try our email course on U.S. immigration

Learn about immigration through five short lessons delivered to your inbox every other day. Sign up now!

For years, proposals have sought to shift the nation’s immigration system away from its current emphasis on family reunification and employment-based migration, and toward a points-based system that prioritizes the admission of immigrants with certain education and employment qualifications.

The Trump administration has announced a proposal that would grant green cards to immigrants who meet requirements related to education, age and English-speaking ability. The administration has previously proposed regulation that would deny immigrants entry to the U.S. or lawful permanent residence if they are likely to use Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly known as food stamps) and other forms of public assistance. Here are key details about existing U.S. immigration programs:

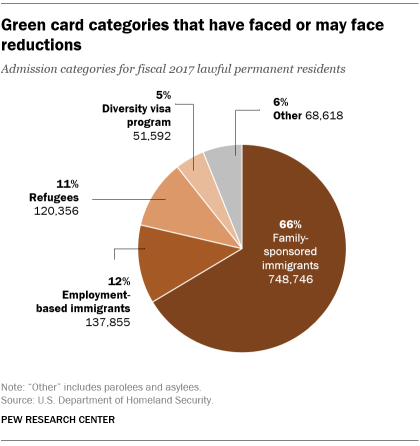

Family-based immigration

In fiscal 2017, 748,746 people received family-based U.S. lawful permanent residence. The program allows someone to receive a green card if they already have a spouse, child, sibling or parent living in the country with U.S. citizenship or, in some cases, a green card. Immigrants from countries with large numbers of applicants often wait for years to receive a green card because a single country can account for no more than 7% of all green cards issued annually. President Donald Trump said his legislation, when proposed, would prioritize family-based green cards to immediate family members. Today, family-based immigration – referred to by some as “chain migration” – is the most common way people gain green cards, in recent years accounting for about two-thirds of the more than 1 million people who receive them annually. This share could decline to about one-third under the president’s proposal.

Refugee admissions

The U.S. admitted 22,491 refugees in fiscal 2018, down from 53,716 in fiscal 2017 – and about half of the 84,995 refugees admitted in fiscal 2016. This decline reflects a lower admissions cap. For fiscal 2019, refugee admissions have been capped at 30,000, the lowest since Congress created the modern refugee program in 1980 for those fleeing persecution in their home countries. One of Trump’s first acts as president in 2017 was to freeze refugee admissions, citing security concerns. Admissions from most countries eventually restarted, though applicants from 11 nations deemed “high risk” by the administration were admitted on a case-by-case basis. In January 2018, refugee admissions resumed for all countries.

Employment-based green cards

In fiscal 2017, 137,855 employment-based green cards were awarded to foreign workers and their families. The Trump administration’s points-based plan would increase the number of green cards granted due to having certain skills. The new system would eliminate a green card for immigrant investors who put money into commercial U.S. enterprises that are intended to create jobs or benefit the economy. This path to a green card, the EB-5 program, has drawn criticism from some lawmakers.

Diversity visas

Each year, about 50,000 people receive green cards through the U.S. diversity visa program, also known as the visa lottery. Since the program began in 1995, more than 1 million immigrants have received green cards through the lottery. Trump has said he wants to eliminate the program, which seeks to diversify the U.S. immigrant population by granting visas to underrepresented nations. Citizens of countries with the most legal immigrant arrivals in recent years – such as Mexico, Canada, China and India – are not eligible to apply. Trump has proposed to eliminate the program as part of his proposal to overhaul how green cards are awarded.

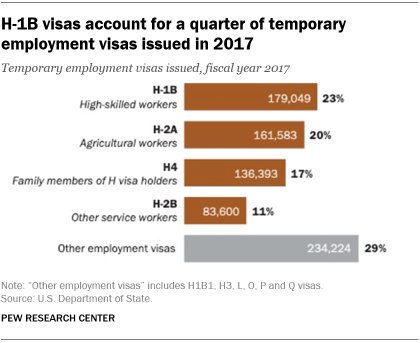

H-1B visas

In fiscal 2017, 179,049 high-skilled foreign workers received H-1B visas. As the nation’s biggest temporary employment visa program, H-1B visas accounted for about a quarter (23%) of all temporary visas for employment issued in 2017. In all, more than 1.6 million H-1B visas were issued from fiscal years 2007 to 2017. The denial rate of H-1B visa applications increased in 2019 under the Trump administration. Meanwhile, more H-1B visas went to immigrants with a U.S. master’s degree or higher. The administration has also said it plans to restrict work permits for spouses of H-1B holders.

Temporary permissions

A relatively small number of unauthorized immigrants who came to the U.S. under unusual circumstances have received temporary legal permission to stay in the country. One key distinction for this group of immigrants is that, despite having received permission to live in the U.S., most don’t have a path to gain lawful permanent residence. The following two programs are examples of this:

DACA

About 700,000 unauthorized immigrants had temporary work permits and protection from deportation through Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals as of Sept. 5, 2017. The program has been central to negotiations as Congress debates changes to U.S. immigration law. Trump ordered an end to the program in September 2017. However, DACA enrollees can remain in the program while federal courts consider cases regarding its future, though the administration is not required to accept new applicants. The U.S. Supreme Court may consider the issue in 2019.

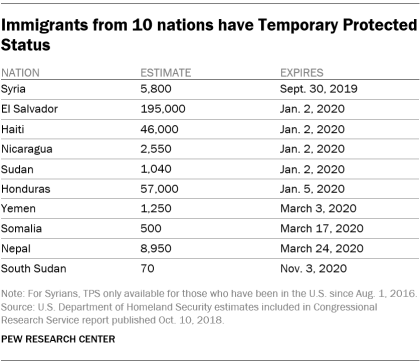

Temporary Protected Status

About 320,000 immigrants from 10 nations have permission to live and work in the U.S. under Temporary Protected Status (TPS) because war, hurricanes or other disasters in their home countries could make it dangerous for them to return. They face an uncertain future in the U.S. The Trump administration has said it will not renew the program for people from El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua and Sudan, who together account for about 98% of enrolled immigrants. However, decisions to end TPS for these countries have been challenged in federal courts, and the government has now extended TPS for all countries into 2020. Only those from Syria, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen have received TPS extensions with the possibility of future renewals.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published Feb. 26, 2018.