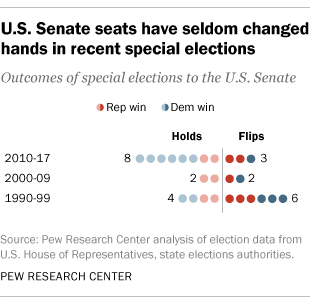

Doug Jones’ narrow victory in Tuesday’s special U.S. Senate election in Alabama did more than make him the first Democrat to win a Senate seat from that state in a quarter-century: It marks the first time since 2010 that a Senate special election has flipped a seat from one party to the other.

Jones, a former federal prosecutor, defeated Republican Roy Moore 49.9% to 48.4% in a race that saw far higher turnout than had been predicted.

Before Jones’ win, the most recent Senate seat to flip in a special election was the Illinois one held by Barack Obama before he became president: Republican Mark Kirk won the seat in November 2010. Earlier that same year, Republican Scott Brown won a special election in Massachusetts for the Senate seat that Democrat Edward Kennedy had held before his death. In the case of Tuesday’s election, the Alabama seat opened up after President Donald Trump named then-Sen. Jeff Sessions as attorney general.

In the eight other special Senate elections held since 2010, the incumbent party has retained its seat (six Democratic, two Republican). That makes special Senate elections similar to their House counterparts: A Pew Research Center analysis earlier this year found that no House seat has flipped in a special election since 2012.

Flipping seats was more common during the 1990s. In the 10 special Senate elections held between 1990 and 1999, three seats flipped from Republican to Democratic, three flipped from Democratic to Republican, and four were held by the incumbent party. The following decade saw a decline in both the number of special Senate elections overall and in flipped seats.

The Moore-Jones race was the 25th special Senate election since 1990, compared with 97 special House elections in the same period. Jones will join 13 other currently serving senators who first won their seats in special elections.

Unlike House vacancies, which the Constitution requires be filled by election, most states allow their governors to appoint temporary senators to fill a vacant seat until an election is held. More often than not, interim senators run in the election to complete the terms of their predecessors, as 14 out of 22 appointees have done since 1990. When they do run, they usually win: Nine of the 14 interim appointees who sought election won. (Alabama’s Luther Strange, who lost the GOP nomination to Moore earlier this fall, is only the second appointed senator since 1990 to lose a primary, after Kansas’ Sheila Frahm in 1996.)

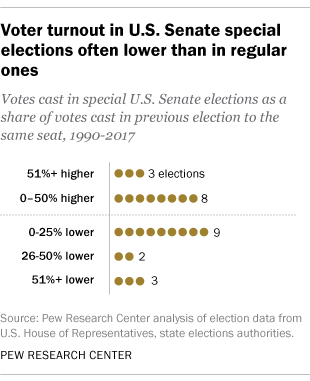

More than 1.3 million Alabamans voted in Tuesday’s race, 40.5% of registered voters. That was much higher than pre-election estimates: Alabama’s secretary of state had said he expected about 25% of the state’s 3.3 million registered voters to cast ballots Tuesday. Turnout was 64% above the level in 2014, when Sessions was re-elected to the seat with only write-in opposition.

That relatively high turnout also sets the Alabama race apart. More often than not, turnout in special Senate elections runs well below that in the immediately prior regular elections for the same seat – on average, almost 14% lower. That’s mainly because of much lower turnout in special elections held on dates other than regularly scheduled Election Days, as the Alabama race was.

In the eight special elections since 1990 held on dates other than a general election, turnout averaged 39.3% lower than the previous regular elections for the same seats. (December is an especially unusual time to hold a special Senate election.) In the 17 special elections that coincided with other regularly scheduled elections, turnout actually averaged 2.3% higher than in the previous regular elections for the same seat.

The highest relative turnout rates for special elections have come in Senate seats where the previous incumbents had faced little serious opposition for many years. For example, Mississippi held a special election in 2008 to fill the seat of Sen. Trent Lott, who had resigned the previous December. When Lott was re-elected in 2006, he took nearly 64% of the vote, but only about 611,000 Mississippians cast ballots that year. In the special election to choose Lott’s successor, twice as many people voted; Republican Roger Wicker won with 55% of the vote.