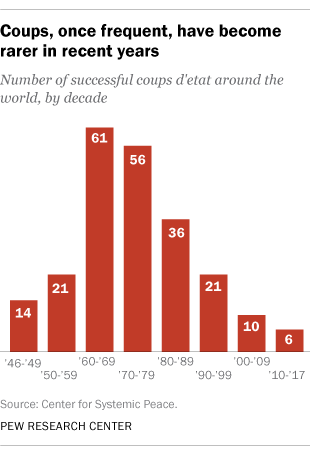

This week’s apparent coup d’etat in Zimbabwe may bring an end to the 37-year-long rule of President Robert Mugabe. It’s the first such seizure of power globally in three years – a reminder of how much rarer coups have become as methods of regime change.

Since the end of World War II, there have been 225 successful coups (counting the events in Zimbabwe) in countries with populations greater than 500,000, according to the Center for Systemic Peace, which maintains extensive datasets on various forms of armed conflict and political violence. Most coups occurred during the height of the Cold War, from the 1960s through the 1980s.

The center defines a coup as “a forceful seizure of executive authority and office by a dissident/opposition faction within the country’s ruling or political elites that results in a substantial change in the executive leadership and the policies of the prior regime, although not necessarily in the nature of regime authority or mode of governance.” It distinguishes coups from other forms of forcible regime change, such as revolutions, civil wars and foreign interventions.

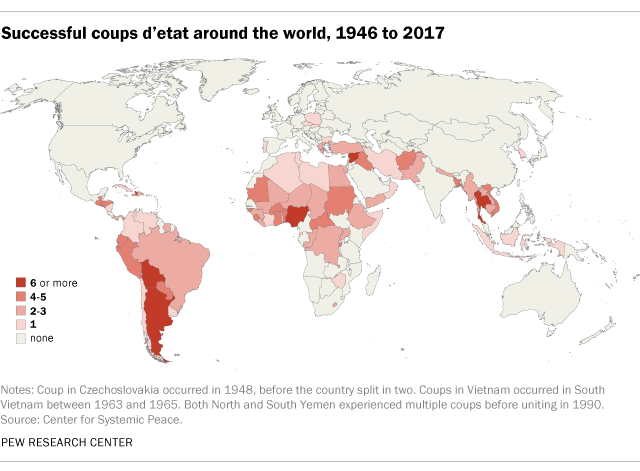

Seventy-seven countries (including a few that no longer exist – Czechoslovakia, North and South Yemen, and South Vietnam) have experienced at least one successful coup since World War II, according to the center’s data. Thailand has had the most coups, with 10; it also was the site of the world’s most recent coup, in May 2014, the culmination of months of political violence and turmoil.

Bolivia and Syria each have had eight coups in the past seven decades, while Argentina has had seven. Scholars who study coups note that they’ve been most common in particular regions: Central and South America, Africa and, to a somewhat lesser extent, the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

In Zimbabwe, an army spokesman has insisted that “this is not a military takeover,” and the military appears to be using a combination of force and negotiation to remove Mugabe from power. But Mugabe’s temporary detention, the arrests of top officials, army control of state broadcasting, roadblocks on major highways and armored vehicles in the streets of Harare all appear to meet the traditional criteria for a coup.

Not all coups succeed: 328 attempted coups have failed in the 177 countries tracked by the center. In fact, the success rate of coup attempts has fallen over time. Only a quarter of the 24 coups attempted so far this decade have succeeded (including Zimbabwe’s, though the situation there is still fluid), compared with well over half between 1946 and 1969. Most recently, a failed coup in Turkey in July 2016 led to a sweeping crackdown on dissent by the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, in which more than 50,000 people have been arrested.

Some scholars argue that coups may not always be bad for democracy, depending on the nature of the overthrown regime and the intent of the new leaders. A 2014 paper in the British Journal of Political Science, for example, found that most coups since the end of the Cold War have been followed by elections within five years, while only about a quarter of coups that took place during the Cold War did so.

Note: This is an update of a post that was first published on July 3, 2013.