See the most recent estimates of the U.S. unauthorized immigrant population, published June 12, 2019.

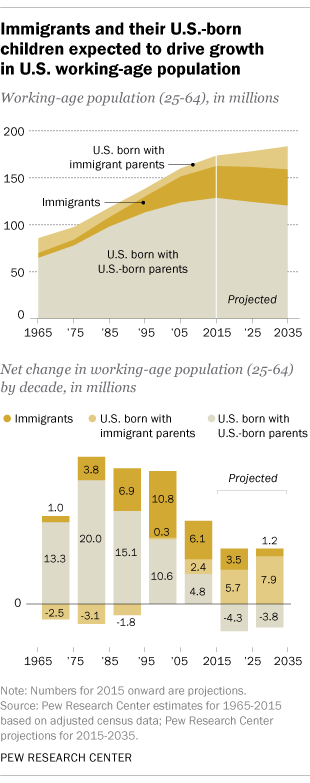

For most of the past half-century, adults in the U.S. Baby Boom generation – those born after World War II and before 1965 – have been the main driver of the nation’s expanding workforce. But as this large generation heads into retirement, the increase in the potential labor force will slow markedly, and immigrants will play the primary role in the future growth of the working-age population (though they will remain a minority of it).

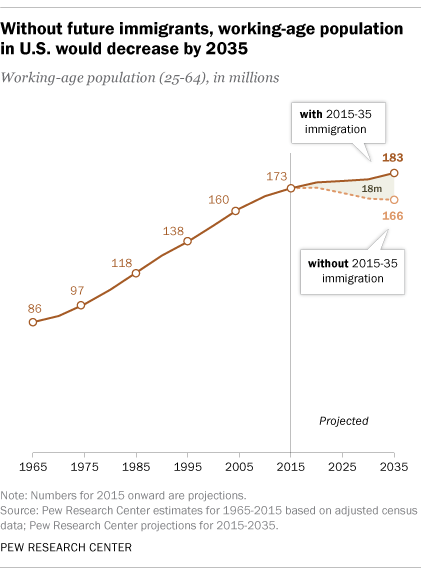

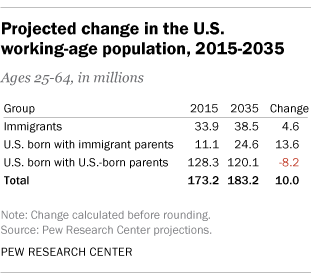

The number of adults in the prime working ages of 25 to 64 – 173.2 million in 2015 – will rise to 183.2 million in 2035, according to Pew Research Center projections. That total growth of 10 million over two decades will be lower than the total in any single decade since the Baby Boomers began pouring into the workforce in the 1960s. The growth rate of working-age adults will also be markedly reduced.

The largest segment of working-age adults – those born in the U.S. whose parents also were born in the U.S. – is projected to decline from 2015 to 2035, both in numbers and as a share of the working-age population. The Center’s projections show a reduction of 8.2 million of these adults, from 128.3 million in 2015 to 120.1 million in 2035.

That numerical loss will be partially offset by an increase in the number of working-age U.S.-born adults with immigrant parents, who are projected to number 24.6 million in 2035, up from 11.1 million in 2015.

But perhaps the most important component of the growth in the working-age population over the next two decades will be the arrival of future immigrants. The number of working-age immigrants is projected to increase from 33.9 million in 2015 to 38.5 million by 2035, with new immigrant arrivals accounting for all of that gain. (The number of current immigrants of working age is projected to decline as some will turn 65, while others are projected to leave the country or die.) Without these new arrivals, the number of immigrants of working age would decline by 17.6 million by 2035, as would the total projected U.S. working-age population, which would fall to 165.6 million.

The Pew Research Center projections for foreign-born working-age adults are based on current rates of immigration, combining lawful and unauthorized. They assume that two-thirds of immigrants arriving through 2035 will be ages 25 to 64, as is true of today’s new immigrants.

The declining number of U.S.-born working-age adults with U.S.-born parents means that they will become a smaller share of the working-age population: 66% in 2035, compared with 74% in 2015. U.S.-born children of immigrants will make up a growing share of working-age adults: 13% in 2035, compared with 6% in 2015. The immigrant share of working-age adults will inch up, from 20% in 2015 to 21% in 2035.

Change by immigrant generation

The decrease in working-age adults born in the U.S. whose parents also were born in the U.S. largely reflects the aging of the Baby Boom generation, born from 1946 to 1964. The youngest Boomers turn 65 by 2030 (of course, some Baby Boomers are immigrants or have immigrant parents, but the share is smaller than among younger Americans). Birth rates, which have stayed relatively low since the 1970s, also play a role.

The largest group joining the nation’s working-age population will be the 60 million people who were born in the country to U.S.-born parents and turn 25 between 2015 and 2035. But they will be outnumbered by U.S.-born adults with U.S.-born parents who turn 65 or who die, according to the projections, and so this group will have a net loss in number.

There will also be 18 million U.S.-born people with immigrant parents who will join the working-age population from 2015 to 2035. This group already lives in the U.S.; they were ages 5 to 24 in 2015. They will outnumber the working-age adults in this group who turn 65 or die over the next two decades, resulting in a net gain of 13.6 million working-age adults who are U.S. born with immigrant parents.

The projections indicate that 17.6 million new immigrants will be added to the working-age population by 2035, offsetting the aging or death of other working-age immigrants. Without them, the number of working-age immigrants would decline by 2035 and the total U.S. working-age population would drop by almost 8 million (or more than 4%) from the 2015 working-age population.

Growth rates and immigration’s role

The relatively weak growth rate projected for the total working-age adult population – averaging 0.3% per year for both the decades between 2015 and 2035 – is well under the increases in recent decades. The annual growth peaked at 2% in the decade from 1975 to 1985, when the Baby Boomers were coming of age, and growth rates were at least 0.8% in all other decades since 1965.

In recent decades, immigration to the U.S. has become an increasing source of growth for the working-age population. It was a negligible source of growth in the 1960s but grew in importance after the 1965 immigration law opened visa eligibility to people from a wider variety of nations than the traditional European countries of origin. By the mid-1990s, immigration had surpassed growth in the number of U.S.-born adults with U.S.-born parents as a source of the increase in the nation’s potential labor force.

These projections, which are based on analysis of census data trends, focus on the working-age population, defined as ages 25 to 64. They exclude young adults, many of whom are enrolled in training programs or higher education, as well as adults ages 65 and older, most of whom are not working. However, the patterns are similar if the age range includes those as young as 18 or as old as 69.

These projections do not look at the future labor force – that is, how many people in each of these groups will be employed or looking for work. Labor-force participation differs by gender and generation. Currently, foreign-born men are somewhat more likely to work than all U.S.-born men (including those with immigrant parents and U.S.-born parents), but foreign-born women are somewhat less likely to work than U.S.-born women, in part because many are staying home to raise children.

Immigrants also play a large role in future U.S. population growth. Assuming current trends continue, future immigrants and their U.S.-born children will account for 88% of the nation’s population growth between 2015 and 2065, according to Pew Research Center projections.