The widespread use of gene editing is rapidly becoming a present-day reality. Thanks to a new method called CRISPR, what once was an esoteric and unwieldy technology has, in just the last few years, become cheaper and more effective.

Thousands of researchers are already using CRISPR (short for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) to edit the DNA in adult cells with an eye toward creating breakthrough medical treatments. But CRISPR also can be used to edit embryos, where changes to the genome will subsequently spiral out into all of a person’s cells and be passed on to his or her offspring.

Embryonic gene editing holds the promise of dramatically enhancing people by making them healthier and more resistant to disease throughout their lives. It also has the potential to make them much smarter, stronger and faster.

Despite these possible benefits, Americans are wary of editing embryos, even if the focus is on using the technology solely to reduce their children’s risk of serious disease, according to a Pew Research Center survey about the broader field of “human enhancement.”

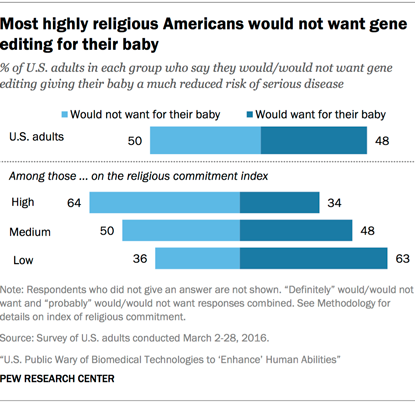

The poll shows a divided public, with half (50%) saying they would not want to use gene editing to lower their own baby’s chances of developing a major ailment and roughly the same share (48%) saying they would use the new technology in this context.

Religious people tend to be more skeptical of embryonic gene editing than those who are less religious. Only 34% of highly religious adults (based on an index of common measures) say they would want to employ gene editing to reduce their child’s risk of disease. Among those who have a low level of religious commitment, almost twice as many (63%) tell us they would want to use the technology on their children. Highly religious Americans tend to see gene editing as crossing a line and “meddling with nature,” while those who are less religious are more inclined to say it is no different than other ways humans have tried to better themselves.

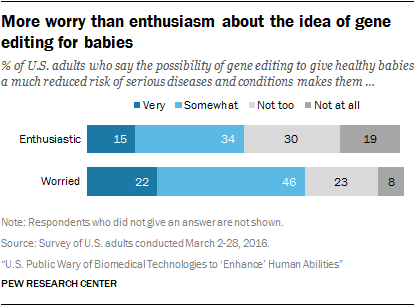

The survey also gauged the intensity of concern or enthusiasm for gene editing, finding that two-thirds of all adults (68%) say this new development makes them “very” or “somewhat” worried. By contrast, only half (49%) say they are “very” or “somewhat” enthusiastic about gene editing. Three-in-ten say they are both worried and enthusiastic about the technology.

A number of medical researchers, including the co-inventor of CRISPR, Jennifer Doudna, argue that scientists should hold off on editing embryos for now because not enough is yet known to safely predict the long-term effects of changes to our genetic blueprint. And although at least one lab in China has already edited embryos, virtually all scientists now using CRISPR are working with adult cells for therapeutic purposes.

Ethics of enhancement

For more on the scientific and ethical dimensions of the human enhancement debate, read our background essay.

Some futurists and ethicists say that while Doudna’s caution is warranted, editing embryos to enhance people’s health and strength should eventually move forward because it has the potential to greatly reduce human suffering and generally make people’s lives better. Other ethicists and religious thinkers, however, argue that enhancement at the embryonic level could dramatically alter what it means to be human and could end up greatly exacerbating existing social tensions (such as economic and social inequality) by creating new classes of privileged “super-people.”

Many Americans have similar concerns. Our new survey found that 73% of adults say gene editing will be used before we fully understand its effects, and 70% believe it will increase inequality.

In addition, a majority of U.S. adults (54%) say that if testing on human embryos were required in order to develop this technology, it would be less acceptable to them. About half (49%) say they would find gene editing less acceptable if it changed the genetic makeup of the whole population (as embryonic gene editing may ultimately do, through the passing on of edited genes to future generations).

Overall, however, Americans are slightly more inclined to say gene editing to give babies a much reduced risk of serious diseases would have more benefits than downsides (36%) than to say downsides outweigh benefits (28%). A third of Americans say the downsides and benefits would be about equal.