In this wild and woolly election season, the White House is by no means the only battleground. Not only are Democrats hoping to regain control of the Senate, but some even have their sights set on the House of Representatives, even though Republicans there hold their largest majority (247-186, with two vacancies) in nearly 90 years. Many GOP leaders also are concerned that troubles at the top of their ticket could lead to significant down-ballot losses, and some have expressed hopes that voters will be willing to split their tickets if the presidential race doesn’t go well.

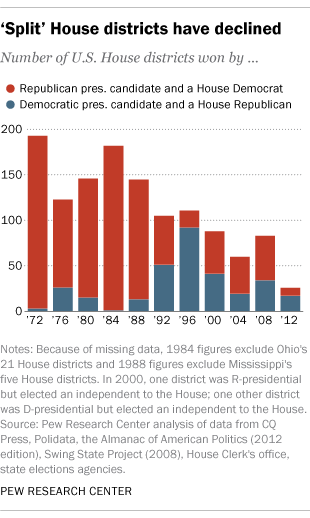

However, districts’ willingness to split their tickets – choose one party’s presidential nominee and the other party’s candidate for representative – has been on a steep decline for more than two decades. In 2012, only 26 House districts out of 435 (6%) split their votes, according to our analysis of district-level election results. Of these, 17 voted to re-elect President Obama but sent a GOP representative to Capitol Hill; nine opted for Mitt Romney and also a Democratic representative. (On an individual voter level, a Pew Research Center analysis in 2014 estimated that about eight-in-ten likely voters in areas with multiple major contests would vote a straight-party ticket that fall. Split-ticket voting also has declined at the state level.)

Split-ticket districts used to be much more common. In Richard Nixon’s 1972 landslide re-election, for example, 190 districts that voted for Nixon also elected Democratic representatives; just three, all in Massachusetts, went for both George McGovern and a GOP representative. As recently as 1988, at least 145 of the 435 House districts went one way for president and the other for representative (Mississippi data were unavailable for that year).

This trend has not gone unnoticed among political observers, and they’ve suggested several possible explanations: increased political polarization, self-sorting of the population, and the advantages of incumbency. But two not unrelated characteristics of split-ticket districts from the days when they were more common go a long way toward explaining why they aren’t anymore.

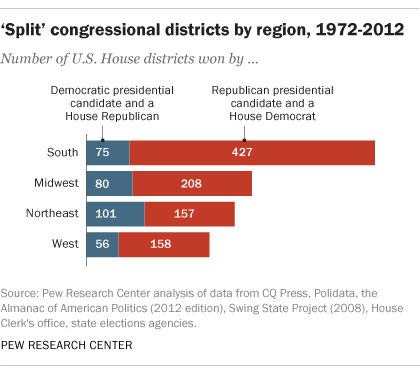

First, split-ticket districts were overwhelmingly Republican for the presidency but Democratic when it came to the House (a combined 92.6% of all split-ticket districts in the five election cycles between 1972 and 1988). And second, tickets in Southern districts were far more likely to be split than those in any other region: Of all districts that split their presidential and House votes between 1972 and 1988, 41.2% were from Southern states even though the South accounted for just 31.5% of all House seats. This was well above the shares in any of the other three Census-defined regions. In 1972, two-thirds of all Southern districts split their presidential and House votes; as recently as 1988 more than half still did.

This was a vestige of the “Solid South,” the decades in which most Southern states were dominated by conservative Democrats. That led, among other things, to long-serving Southern Democratic senators and representatives who faced little real opposition at election time. Democratic dominance was already waning by the 1970s, at least at the presidential level, but took longer to fade in Congress and in state government. By 2012, voters in only eight Southern districts split their presidential and House votes – just 5% of the country’s split districts that year.