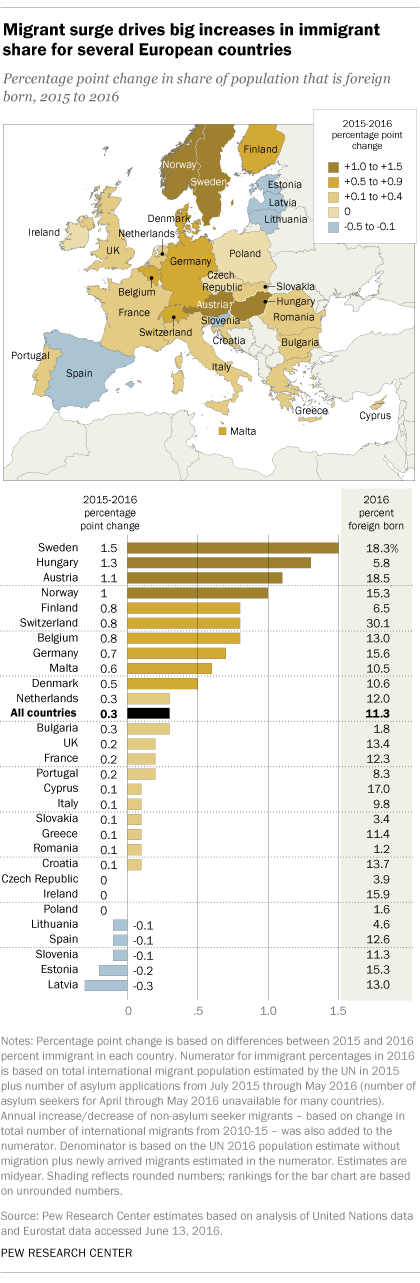

The recent historic migration surge into Europe has led to a large increase in the immigrant share of populations in many nations there, with the notable exceptions of the UK and France, which saw more modest increases, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of United Nations and Eurostat data.

From July 2015 to May 2016, more than 1 million people applied for asylum in Europe. The immigrant share of the population increased most during this time in Sweden, Hungary, Austria and Norway, which each saw an increase of at least 1 percentage point. While that rise might seem small, even a 1-point increase in a single year is rare, especially in Western countries. (The immigrant share of the U.S. population increased by about 1 point over a decade, from 13% in 2005 to about 14% in 2015.)

Recent migrants added to already substantial foreign-born populations living in Sweden, Norway and Austria – all nations in which the foreign born make up 15% or more of the population in 2016. Sweden had the greatest increase, rising from about 16.8% in 2015 to 18.3% in 2016, a 1.5-percentage-point increase. The foreign-born shares in Norway (15.3% in 2016) and Austria (18.5% in 2016) increased by about 1 point over the same period.

Countries with smaller immigrant populations like Hungary and Finland also saw their foreign-born shares increase significantly due to the 2015-2016 migration surge. Hungary’s foreign-born share rose from 4.6% in 2015 to 5.8% in 2016, a 1.3-point increase. In Finland, the share of foreign born rose an estimated 0.8 points, from 5.7% to 6.5%.

Several European countries, however, saw little change in their percent foreign born between 2015 and 2016. The United Kingdom and France – countries with significant immigrant populations – received far fewer asylum applicants relative to their population size in 2015-16 than other countries, and each saw a relatively modest 0.2-percentage-point increase in their foreign-born shares (to 13.4% in the UK and 12.3% in France for 2016).

Germany received the most asylum seekers of any European country. But because of its large population, its foreign-born share rose by an estimated 0.7 percentage points to 15.6% in 2016, a substantial but significantly smaller increase than in other European countries. On the other end of the spectrum, nations including Lithuania, Spain, Slovenia, Estonia and Latvia saw their immigrant shares decrease during this time. This is in part because these countries did not receive a high number of asylum seekers during the past year. In addition, their existing foreign-born population is declining as immigrants return home (as in Latin Americans in Spain) and aging immigrants die (as in Latvia).

Many European Union countries, Norway and Switzerland are part of the Schengen agreement, which allows for free movement across European countries without border inspections. When combining the populations of EU countries, Norway and Switzerland, the percent living outside their home country increased 0.3 percentage points.

Even after the 2015-2016 migration surge, immigrant shares in most European countries are not as high as in many other countries worldwide. In Canada (22%) and Australia (28%), roughly one-in-four residents are foreign born as of 2015. In Qatar (75%) and the United Arab Emirates (88%), at least three-quarters of the population is foreign born, including many who have been actively recruited as foreign labor.

The size of immigrant populations will likely change as migration into Europe shifts. Not all asylum seekers will be granted refugee status in Europe, which means some migrants will be returned to their home countries. And in Greece, migration has largely been halted due to an agreement to divert refugees to Turkey and other EU nations. Nonetheless, asylum seekers continue to enter Europe, most recently with sub-Saharan Africans crossing the Mediterranean Sea and into Italy.

Correction: An earlier version of the chart in this post gave an incorrect year in the footnote text. It has been updated.