The future belongs to the young. But what if there are not many of them?

Nowhere is this more evident than in Europe, a rapidly aging region facing severe economic challenges. What the dwindling youthful population of Europe believes and how their views differ from their aging and far more numerous elders may go a long way toward determining Europe’s fate.

European Millennials are young people who came of age politically, economically and socially as the 21st century – and the new millennium – began. In 2014, they ranged in age from 18 to 33. (For more on American Millennials, who are also defined by their shared cultural and historical experience, see the Pew Research Center’s extensive research work.)

Millennials accounted for 24% of the adult population in the 28-member European Union in 2013, the last year for which there is comparable, comprehensive EU demographic data. In comparison, this generation represented about 27% of the adult population in the United States in 2014, and this year they are expected to become the largest generation, overtaking Baby Boomers.

But the generational picture is very different in Europe. In 2014, the Pew Research Center surveyed the public in seven European countries. In all of them, Millennials accounted for a minority of the adult population, ranging from 28% of the Polish population to just 19% of the Italian population. In every country surveyed, and in the EU as a whole, people ages 50 and older accounted for a far higher proportion of the overall population: 52% in Germany, 51% in Italy and 47% overall.

The largest absolute number of Millennials in a survey country was in Germany: 14.68 million. The smallest number was in Greece: 2.02 million.

Just like American Millennials, European Millennials have lived through an economic crisis since 2008. Only, in Europe, it shows little sign of ending. While the U.S. has seen its economic indicators continue to rise, the picture is more bleak in Europe, where the International Monetary Fund forecasts Germany growing at only 1.3%, France by 0.9% and Italy by 0.4% in 2015.

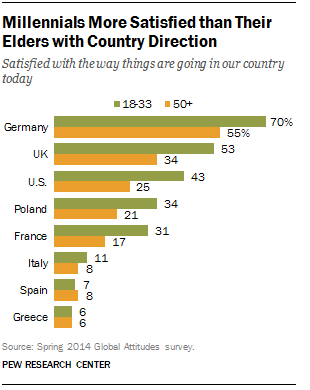

Economic stagnation has exacted a heavy toll on public sentiment. Barely a fifth (22%) of Europeans are satisfied with the way things are going in their countries, according to the 2014 Pew Research Center survey.

And European Millennials are no exception. Just 6% of young Greeks and 7% of Spaniards ages 18 to 33 are satisfied with the direction of their country.

But not all youthful Europeans despair. Possibly reflecting the milder impact of Europe’s economic crisis on young people in northern Europe, in some parts, Millennials’ outlook is much more cheery than that of their elders. When asked their views about the direction of their country, in the United Kingdom more than half of Millennials (53%) say they are satisfied, compared with 34% of older British. And in Germany, there’s a 15 percentage point difference.

Moreover, most European Millennials are satisfied with their own lives. When asked to place themselves on a ladder where 10 represents the best possible life and zero represents the worst possible life, a median of 56% say they currently stand somewhere between the seventh and 10th step.

Young Germans (66%), living in the strongest economy in Europe, are the most satisfied; young Greeks (45%), the least happy. Given recent economic troubles in Greece that have left roughly half of young Greeks out of work, the fact that so many Greek Millennials are nevertheless happy with their lives demonstrates that life satisfaction is derived from a number of factors, not just the state of the economy.

Europeans born after 1980 are also more likely to be satisfied with their situation in life than are people born before 1965. This generational difference in happiness is particularly apparent in Poland (51% of young people are satisfied vs. 31% of those 50 years of age and older), Greece (45% vs. 32% respectively) and Spain (61% vs. 49%).

Nevertheless, European Millennials have a notably negative outlook about prospects for the next generation. When asked whether they thought children in their country would be better off financially than their parents once they grow up, only 38% of young British, 37% of young Germans and 15% of young French were optimistic. But even such somber perspectives are relative. As downbeat as Millennials may be about prospects for the next generation, their elders are even more pessimistic: Just 19% of older British see a brighter financial future for their children.

And this is a perspective that European Millennials share with young Americans. Only 37% of American Millennials express the view that the next generation will be better off, hardly a ringing endorsement of their future. But that is significantly more optimistic than the opinion of Americans 50 years of age and older: Only 24% of them voice hope for the next generation’s financial future.

Read more: