Note: An updated version of this post was published on April 22, 2022.

It’s been 50 years since the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970. The event – a “teach-in on the environment” launched by U.S. Sen. Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin – called attention to the aftermath of a massive oil spill off the Santa Barbara coast the prior year. The protest helped set the political stage for a decade of new regulations, including the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act.

Earth Day has since expanded across the globe, bringing citizens together – at least virtually for 2020 – to educate, mobilize and celebrate. While the event focuses on a range of environmental concerns, climate change has loomed especially large over the past decade, sometimes sparking major protests urging more action to reduce it and its effects.

This year’s Earth Day comes at a unique moment. People in many countries remain under stay-at-home orders to help mitigate the spread of the coronavirus, and the resulting shifts in transportation, industrial activity and consumer habits are leading to a decline in carbon emissions. Whether such declines will be temporary or lasting remains unclear.

For Earth Day 2020, we take stock of U.S. public opinion about global climate change and the environment, based on recent Pew Research Center surveys.

How we did this

The data for this post was drawn from multiple surveys. Many findings are from a Pew Research Center survey conducted Oct. 1-13, 2019, among 3,627 U.S. adults.

The October 2019 and Jan. 7-21, 2019, surveys were conducted using the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This allows for nearly all U.S. adults to have a chance of selection. The surveys are weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology. Separate surveys were conducted Jan. 8-13, 2020, and Jan. 9-14, 2019, by telephone through a sample of randomly selected U.S. adults.

Here are the questions and responses for surveys used in this post, as well as each survey’s methodology:

- Jan. 8-13, 2020 survey: Questions | Methodology

- Oct. 1-13, 2019 survey: Questions | Methodology

- Jan 7-21, 2019 survey: Questions | Methodology

- Jan. 9-14, 2019 survey: Questions | Methodology

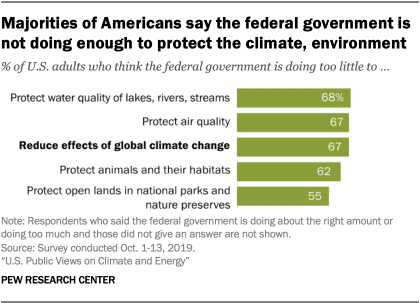

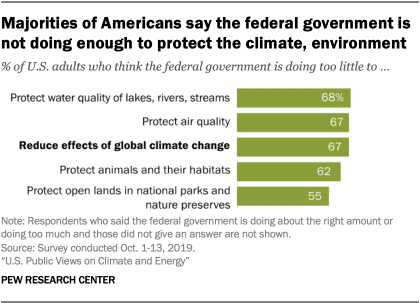

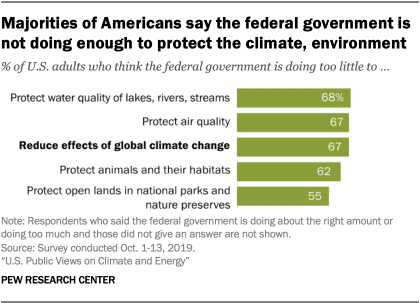

Two-thirds of U.S. adults say the federal government is doing too little to reduce the effects of global climate change. Similar shares say the government is doing too little to protect water (68%) and air quality (67%), while majorities say the same when it comes to protecting animals and their habitats (62%) and protecting open lands in the national parks (55%).

These findings from an October 2019 survey come amid ongoing efforts to roll back regulations designed to protect the environment, including relaxing limits on methane and carbon emissions.

Public concern about climate change has remained steady even as concerns about the spread of infectious diseases have risen. In a survey last month, six-in-ten Americans said global climate change is a major threat to the country, up from 44% in 2009. Respondents who took the survey in the latter part of the month – after the March 13 declaration of a national emergency due to the coronavirus – were about equally concerned about climate change as those interviewed earlier in the month.

See also: U.S. concern about climate change is rising, but mainly among Democrats

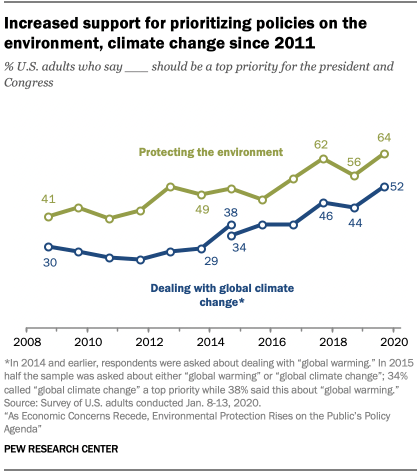

Compared with a decade ago, more Americans say protecting the environment and dealing with global climate change should be top priorities for the president and Congress. Nearly two-thirds of U.S. adults (64%) say protecting the environment should be a top priority for the president and Congress, while about half (52%) say the same about dealing with global climate change, according to a January 2020 survey. These shares have grown considerably since 2011.

Partisanship remains a major factor in these priorities. More Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (85%) think protecting the environment should be a top priority for the president and Congress than do Republicans and GOP leaners (39%). Most of the increase in the share of people who prioritize climate change has come among Democrats, not Republicans.

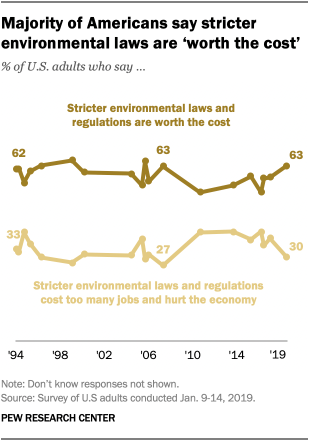

A 63% majority of Americans say stricter environmental regulations are worth the cost. When asked to choose, most Americans say stricter environmental regulations are worthwhile, while 30% think such laws and regulations cost too many jobs and hurt the economy. Public views on this issue have fluctuated from year to year, although the balance of opinion is nearly the same as it was when first asked 25 years ago.

There are wide partisan divides on this question. As of early 2019, 81% of Democrats (and independents who lean to the Democratic Party) had a positive view of stricter environmental regulations, compared with 45% of Republicans and GOP-leaning independents. Most conservative Republicans (60%) say environmental regulations cost too many jobs and hurt the economy. GOP moderates and liberals take the opposite view: 60% in this group say such regulations are worth the cost.

A majority of Americans see at least some local effects of climate change. In October 2019, about six-in-ten Americans (62%) said that global climate change was affecting their local community a great deal or some. Those who said this were asked which of several possible effects were impacting their area. Most considered long periods of hot weather (79% of those asked) and severe weather patterns such as floods or storms (70%) to be major ways that climate change has affected their local community.

The types of effects people say they experience due to climate change tend to vary across regions. For example, among those who say they see at least some local impacts of climate change, more of those in the Pacific (83%) and Mountain (78%) regions say increasing wildfire activity is a major effect of climate change where they live. This compares with about half or fewer of those living in the South (52%), Northeast (46%) or Midwest (40%).

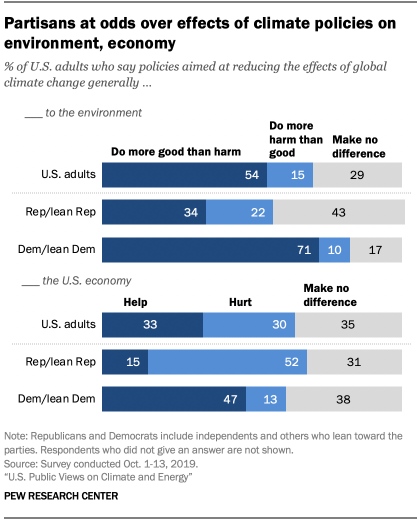

Republicans and Democrats differ over the effects of climate policies for the environment and for the economy. In the October 2019 survey, two-thirds of Americans (67%) said the federal government wasn’t doing enough to reduce the effects of global climate change. But there were wide political divides over the effects of climate policy. For example, 71% of Democrats said policies aimed at reducing climate change generally provide net benefits for the environment, compared with roughly a third of Republicans (34%). Instead, 43% of Republicans said such policies make no difference and about two-in-ten (22%) said they do more harm than good for the environment.

Republicans see more risk than Democrats when it comes to the economic effects of climate policies. Around half of Republicans (52%) said in 2019 that such policies hurt the economy. In contrast, most Democrats said climate policies either help (47%) or make no difference (38%) to the economy.

Millennial Republicans differ from Baby Boomer and older Republicans on a range of questions related to the environment. There is strong consensus among Democrats that the federal government is doing too little on key aspects of the environment, such as protecting water and air quality and reducing the effects of climate change. But among Republicans, there are sizable differences in views by generation. Millennial and younger Republicans – adults born in or after 1981 – are more likely than Republicans in the Baby Boomer or older generations to think government efforts to reduce climate change are insufficient (52% vs. 31%).

GOP Millennial and Gen Z adults are also less inclined than older Republican generations to prioritize fossil fuel development. For example, 78% of Millennial and Gen Z Republicans say the development of alternative energy sources should be a priority for the United States over the expansion of fossil fuel sources, compared with 53% of Republicans in the Baby Boomer or older generations.

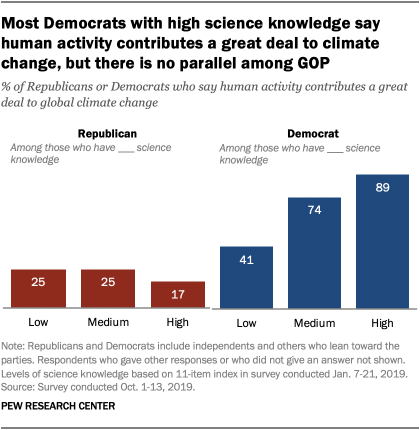

Partisanship is a stronger factor in people’s beliefs about climate change than is their level of knowledge and understanding about science. In October 2019, roughly nine-in-ten Democrats with a high level of knowledge about science (89%) said human activity contributes a great deal to climate change, compared with 41% of Democrats with low science knowledge, based on an 11-item knowledge index. By contrast, Republicans with a high level of science knowledge were no more likely than those with a low level of knowledge to say human activity plays a strong role in climate change. A similar pattern was found regarding people’s beliefs about energy issues. These findings illustrate that the relationship between people’s level of science knowledge and their attitudes can be complex.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published on April 19, 2019.