Americans have long been divided in their views about the trade-off between security needs and personal privacy. Much of the focus has been on government surveillance, though there are also significant concerns about how businesses use data. The issue flared again this week when a federal court ordered Apple to help the FBI unlock an iPhone used by one of the suspects in the terrorist attack in San Bernardino, California, in December. Apple challenged the order to try to ensure that security of other iPhones remained protected, and also to provoke a wider national conversation about how far people would like technology firms to go in protecting their privacy or cooperating with law enforcement.

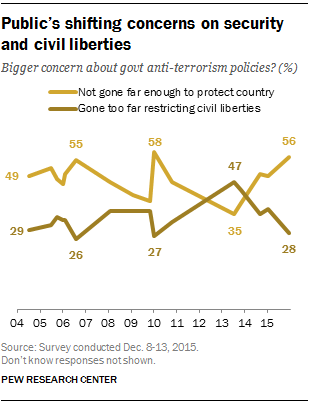

Events have had a major impact on public attitudes on this issue. Terrorist attacks generate increased anxieties. For instance, the San Bernardino and Paris shootings in late 2015 had a striking impact. A Pew Research Center survey in December found that 56% of Americans were more concerned that the government’s anti-terror policies have not gone far enough to protect the country, compared with 28% who expressed concern that the policies have gone too far in restricting the average person’s civil liberties. Just two years earlier, amid the furor over Edward Snowden’s revelations about National Security Agency surveillance programs, more said their bigger concern was that anti-terror programs had gone too far in restricting civil liberties (47%) rather than not far enough in protecting the country (35%).

At the same time, there are other findings suggesting that Americans are becoming more anxious about their privacy, especially in the context of digital technologies that capture a wide array of data about them. Here is an overview of the state of play as the iPhone case moves further into legal proceedings.

How people have felt about government anti-terror policies

Pew Research Center surveys since the 9/11 terrorist attacks have generally shown that in the periods when high-profile cases related to privacy vs. security first arise, majorities of adults favor a “security first” approach to these issues, while at the same time urging that dramatic sacrifices on civil liberties be avoided. New incidents often result in Americans backing at least some extra steps by the law enforcement and intelligence communities to investigate terrorist suspects, even if that might infringe on the privacy of citizens. But many draw the line at deep interventions into their personal lives.

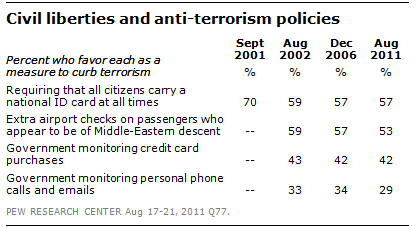

For instance, our survey shortly after the 9/11 attacks found that 70% of adults favored requiring citizens to carry national ID cards. At the same time, a majority balked at government monitoring of their own emails and personal phone calls or their credit card purchases.

It should be noted that surveys have also found that people’s immediate concerns about security can subside over time. In a poll conducted in 2011, shortly before the 10th anniversary of 9/11, 40% said that “in order to curb terrorism in this country it will be necessary for the average person to give up some civil liberties,” while 54% said it would not. A decade earlier, in the aftermath of 9/11 and before the passage of the Patriot Act, opinion was nearly the reverse (55% necessary, 35% not necessary).

When The New York Times reported in late 2005 that President George W. Bush authorized the NSA to eavesdrop on Americans, subsequent Pew Research Center surveys found that 50% of Americans were concerned that the government hadn’t yet gone far enough in protecting the country against terrorism, and 54% said it was generally right for the government to monitor the telephone and email communications of Americans suspected of having ties with terrorists without first obtaining court permission. Some 43% said such surveillance was generally wrong. Quite similar numbers were found in a survey at when President Barack Obama took office in 2009.

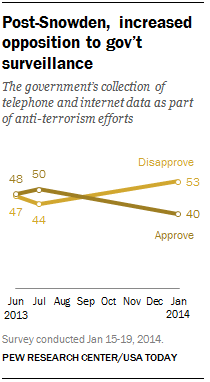

Right after the Snowden revelations in June 2013, a Pew Research Center poll found that 48% of Americans approved of the government’s collection of telephone and internet data as part of anti-terrorism efforts. But by January 2014, approval had declined to 40%.

And many Americans continue to express concern about the government’s surveillance program. In an early 2015 online survey, 52% of Americans described themselves as “very concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about government surveillance of Americans’ data and electronic communications, compared with 46% who described themselves as “not very concerned” or “not at all concerned” about the surveillance.

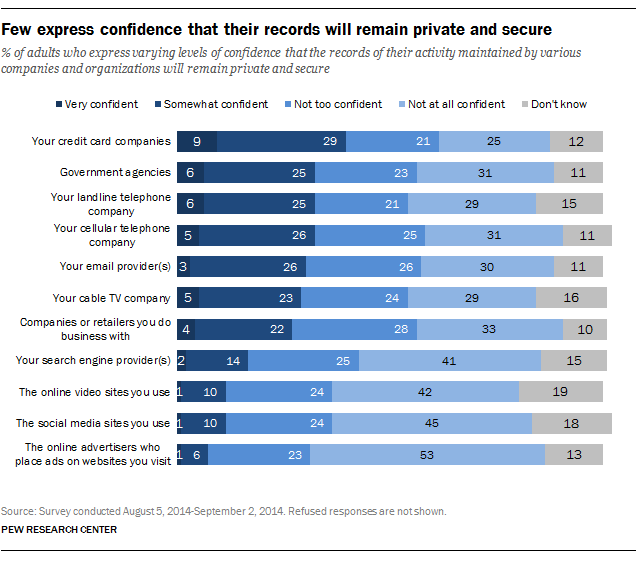

How people feel about corporate practices

As businesses increasingly mine data about consumers, Americans are concerned about preserving their privacy when it comes to their personal information and behaviors. Those views have intensified in recent years, especially after big data breaches at companies such as Target, eBay and Anthem as well as of federal employee personnel files. Our surveys show that people now are more anxious about the security of their personal data and are more aware that greater and greater volumes of data are being collected about them. The vast majority feel they have lost control of their personal data, and this has spawned considerable anxiety. They are not very confident that companies collecting their information will keep it secure.

In assessing public attitudes, context matters – and so does how the question is framed

One consistent finding over the years about public attitudes related to privacy and societal security is that people’s answers often depend on the context. The language of the questions we ask sometimes affects the way people respond.

A recent Pew Research Center study showed that, in commercial situations, people’s views on the trade-off between offering information about themselves in exchange for something of value are shaped by both the conditions of the deal and the circumstances of their lives. People indicated that their interest and overall comfort level in sharing personal information depends on the company or organization with which they are bargaining and how trustworthy or safe they perceive the firm to be. It also depends on what happens to their data after they are collected, especially if the data are made available to third parties, and on how long the data are retained.

A study in the wake of the Snowden revelations showed that there was notable change in public attitudes about NSA surveillance programs when questions were modified. For instance, only 25% favored NSA surveillance when there was no mention of court approval of the program. But 37% favored it when the program was described as being approved by courts. Similarly, characterizing the government’s data collection “as part of anti-terrorism efforts” garnered more support than not mentioning this (35% favored vs. 26% favored).