The American food scene has undergone considerable change over the past two decades. During this period, the public has seen the introduction of genetically modified crops, the mainstreaming of organic foods into America’s supermarkets,4 and the proliferation of chefs elevated to celebrity status within popular culture.

Over the same period, there has been a marked increase in public health concerns about the growing prevalence of obesity among both children and adults. Perhaps sparked by thinking from people such as Michael Pollan,5 Mark Bittman, 6 and documentaries such as Morgan Spurlock’s “Super Size Me,” Americans thinking about food has shifted dramatically.

Concerns about obesity, food allergies and other health effects of food are fueling a new level of scrutiny of chemicals and additives in foods and contribute to shifting notions about portion size, sugar and fat content.7 Consumption of sugary sodas has dropped to a 30-year low while sales of bottled and flavored water rose dramatically over the past few decades. Zero-calorie diet sodas long held allure for Americans concerned about their weight, but sales of diet sodas have also dropped, with at least some arguing that the decline has been fueled by growing public concern about ingesting artificial sweeteners and other food additives.8 America’s love affair with fast-food chains is on the wane, with “fast casual” brands that offer convenient options which focus on natural, fresh ingredients gaining favor.9

To some degree this is reflected in the emergence of distinct groups that can be identified by their focus on food issues and personal eating habits. New thinking about ways to eat healthy helped launch a number of eating “movements” with proponents arguing that Paleo, anti-inflammatory or vegan diets bring health benefits along with better weight control. Food and the way we eat has become a potential source of social friction as people follow their own ideologies about what to eat and how foods connect with people’s ailments.

During this same period, there have been sometimes strident public debates over science-related topics – most prominently on climate change, but also on a host of others including the environmental impacts of fracking and nuclear power, the safety of childhood vaccines and, of course, the safety of genetically modified foods. A previous Pew Research Center report showed that public attitudes on a wide range of science issues were widely divergent from those of members of the American Association of Advancement of Science (AAAS). In fact, the largest differences between the public and members of the AAAS were beliefs about the safety of eating genetically modified (GM) foods. Nearly nine-in-ten (88%) AAAS members said it is generally safe to eat GM foods compared with 37% of the general public, a difference of 51 percentage points. The wide differences of opinion over GM foods is connected with a broader public discourse over the role of science research and, perhaps, scientific expertise in understanding and crafting policy solutions.

This new Pew Research Center survey explores public thinking about scientists and their research on GM foods in some detail. As such, this survey can help address the ways in which public views of and trust in scientists may contribute to an opinion divide between the public and members of the scientific community on these issues.

In broad strokes, the survey shows that Americans believe the public is paying more attention to healthy eating today than they did 20 years ago. But, it is not clear to the public whether people are actually eating healthier today. About half of U.S. adults think the eating habits of Americans are less healthy today than they were 20 years ago and most point the blame at both the quantity and quality of what people eat.

Many Americans adopt their own food and eating philosophies because they have to – or want to. Some 15% of U.S. adults say they have at least mild allergies to one or more foods and another 17% have intolerances to foods. Food allergies are more common among women, blacks and people with chronic lung conditions such as asthma. A small minority of Americans describe themselves as either strictly or mostly eating vegan or vegetarian diets.

Americans are paying attention to healthy eating, but many miss the mark

Collectively, the American public is paying more attention to healthy eating, but not fully embracing what they learn. At least, that’s how most Americans see things, according to this survey.

Some 54% of Americans say that compared with 20 years ago, people in the U.S. pay more attention to eating healthy foods today. Smaller shares say people pay less attention (26%) or about the same amount of attention (19%) to eating healthy today.

But 54% of Americans say eating habits in the U.S. are less healthy than they were 20 years ago. A minority (29%) say eating habits are healthier today, while 17% say they are about the same.

The public points the finger at both quality and quantity in Americans’ eating habits. When asked which is the bigger source of problems in Americans’ eating habits, more say the issue is what people eat, not how much (24% vs. 12%). But a 63% majority says that both are equally big problems in the U.S. today.

These beliefs are somewhat tied to people’s focus on food issues. People who care a great deal about the issue of GM foods are particularly likely to say Americans’ eating habits have deteriorated over the past two decades: 67% hold this view, compared with 53% among those not at all or not too concerned about the GM foods issue. People focused on eating healthy and nutritious are relatively more inclined to say the types of food people eat is a bigger problem in the U.S. today than the overall amount (34%, compared with 21% among those not at all or not too focused on healthy and nutritious eating.)

What’s driving public attention to eating? One factor may be a belief in the oft-repeated adage “you are what you eat.” Roughly seven-in-ten adults (72%) say that healthy eating habits are very important for improving a person’s chances of living a long and healthy life.

A similar share (71%) says getting enough exercise is very important. Some 61% say safe and healthy housing conditions are very important. But fewer – 47% – believe genetics and hereditary factors are critical to improving a person’s chances of a long and healthy life. Thus, most Americans consider their future health within their own grasps — if only they eat and exercise adequately.

People focused on food issues are particularly likely to believe that healthy eating habits are important. Fully 86% of those focused on eating healthy and nutritious say that healthy eating habits are very important, compared with 56% among those with little focus on eating healthy and nutritious. And, 87% of those with a deep personal concern about the issue of GM foods say that healthy eating habits are very important for a long and healthy life, compared with 68% among those with no or not too much concern about the GM foods issue.

Americans have a variety of eating styles and philosophies about food

Americans have many different approaches to eating. More say they focus on taste and nutrition than say they focus on convenience. Almost one-quarter (23%) of Americans say the statement “I focus on the taste sensations of every meal” describes them very well, while another 53% say this statement describes them fairly well. Similar shares say their “main focus is on eating healthy and nutritious,” with 18% saying this statement describes them very well and 55% saying it describes them fairly well.

Smaller shares say the statements “I usually eat whatever is easy and most convenient” and “I eat when necessary but don’t care very much about what I eat,” describe them very well (12% and 7%, respectively). People with a particular concern about the GM foods issue and people focused on eating healthy and nutritious are less likely to describe themselves as unconcerned about what they eat.

But, when Americans judge their own eating habits, a majority see themselves falling short. Some 58% of U.S. adults say that “most days I should probably be eating healthier.” About four-in-ten (41%) hit their eating targets about right, saying they eat about what they should most days.

Those who are focused on eating healthy are, by and large, satisfied with their eating. Seven-in-ten (70%) of this group says they eat about what they should on most days. By contrast, 86% of people who describe themselves as not at all or not too focused on healthy eating say they should probably be eating healthier on most days.

There are more modest differences in eating assessments by degree of concern about the issue of GM foods; 51% of those who care a great deal about the issue of GM foods says they eat about they should most days, compared with 37% of those with no particular concern or not too much concern about this issue.

Sizable minority of Americans have food allergies or intolerances to foods

More children and adults are experiencing allergic reactions to foods today. Concern about food allergies and sensitivities can be seen in many places – from the regulations governing the public school lunch program to the way restaurants and food manufacturers package and offer alternatives to the most common allergens.10 For example, people with lactose intolerance can now choose from a wide range of milk and dairy alternatives made from soy and nuts. People allergic to the gluten in wheat can choose among special menu selections, even whole bakeries devoted to gluten-free options.

About 15% of U.S. adults say they have severe, moderate or mild allergies to at least one kind of food. Another 17% of adults have food intolerances, but no food allergies. Roughly seven-in-ten of the adult public (69%) has no food intolerances or allergies.

More women than men report food allergies. About two-in-ten (19%) women say they have severe, moderate or mild food allergies, compared with 11% of men. And, blacks are more likely to say they have food allergies (27%) than either whites (13%) or Hispanics (11%). In other respects, those with food allergies reflect a mix of demographic and educational backgrounds11

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports a higher prevalence of asthma among children with food allergies. The Pew Research Center survey finds 29% of adults with asthma or another chronic lung condition have food allergies, compared with 12% among those who do not have chronic lung conditions.

Vegans and vegetarians are a small minority of U.S., but they are a bit more common among younger generations and liberal Democrats

Vegetarianism has been around for centuries and interest in following this diet – most commonly defined as omitting meat and fish – has waxed and waned over time. Today, vegetarian options are commonplace at many restaurants and food proprietors. Some of those who avoid meat and fish go a step further; vegans typically omit all foods that originate from animals including eggs and dairy products. But some people who consider themselves either vegetarian or vegan are “flexible” about what they eat and at least occasionally veer from these eating principles.

The Pew Research Center survey asked for people’s own assessment of whether the terms vegan and vegetarian applied to them. A small minority – 9% – of U.S. adults identifies as either strict vegetarians or vegans (3%) or as mostly vegetarian or vegan (6%). The vast majority of Americans (91%) say they are neither vegetarian nor vegan.

Younger generations are more likely than others to identify as at least mostly vegan or vegetarian. Some 12% of adults ages 18 to 49 are at least mostly vegan or vegetarian, compared with 5% among those ages 50 and older. Men and women are equally likely to be vegan or vegetarian. There are no differences across region of the country, education or family income in the share who is vegan or vegetarian. There are more liberal Democrats in the vegan and vegetarian group, however. Some 15% of liberal Democrats are at least mostly vegan or vegetarian, compared 4% among conservative Republicans.12

People who have food allergies are more likely to be vegan or vegetarian, suggesting that some food restrictions stem from adverse reactions to certain foods. Among adults with food allergies, 21% identify as strictly or mostly following vegan or vegetarian diets. Just 8% of adults with food intolerances (but no allergies) and 6% of adults with neither food allergies nor intolerances are vegan or vegetarian. Thus, about a third of people who identify as at least mostly vegan or vegetarian also report food allergies.

Social networks: friends eat like friends

People tend to cluster together in social networks with others who are similar. The Pew Research Center survey finds this social pattern also occurs when it comes to people’s eating philosophies and dietary habits.

Most Americans say that at least some of their closest friends and family focus on eating healthy and nutritious. Some 68% say this, while 32% say only a few or none of their friends and family does this.

Adults who say the statement “my main focus is on eating healthy and nutritious” describes them at least very or fairly well are more likely to say at least some of their closest family and friends do the same.

A minority of the population (24%) says that most or some of their closest family and friends have food intolerances or food allergies. Among those who say that they, personally, have severe to mild allergies to some foods, a larger share (51%) says at least some of their closest family and friends also have intolerances or allergies.

A similar pattern occurs when it comes to vegetarians and vegans. Some 12% of U.S. adults say that at least some of their close family and friends are vegan or vegetarian. But there are stark differences in social network composition among those who are, personally, vegan or vegetarian and those who are not. Fully 52% of people who are at least mostly vegan or vegetarian say that some or most of their closest family and friends also follow vegan or vegetarian diets. Just 8% of people who are not themselves vegan or vegetarian say the same.

Many Americans say it’s good party hosting behavior to inquire about food restrictions; few say it bothers them when guests ask for dietary accommodations

Businesses have changed what foods they offer and how foods are packaged to accommodate Americans’ diverse dietary needs and preferences over the past decade or more. What do people think about accommodating people’s eating needs and preferences at private social gatherings? The Pew Research Center survey finds 37% of Americans say that, when hosting social gatherings, the host should always ask guests ahead of time if they have any food restrictions or allergies. One-quarter say they should do this sometimes, while 37% believe the host should never or not too often ask about food restrictions before hosting social gatherings.

When they are the host, a minority (31%) of Americans say it bothers them at least some when guests ask for special kinds of food options at their social gatherings. Larger shares say it bothers them not too much (37%) or not at all (30%) when someone asks for special food accommodations at their social gatherings.

Americans’ beliefs about proper hosting behavior tend to be related to their own food ideologies. About half (49%) of those with a deep personal concern about the GM foods issue say that hosts should always ask guests about dietary needs; this compares with 32% of those with no or not too much concern about the GM foods issue. But people who themselves have food allergies are about equally likely as other adults to say that a host should ask about food allergies ahead of a gathering. And, like other Americans, a minority of those focused on food issues say they are bothered at least some when guests ask for special food options at a gathering they host.

Food studies and their conflicting findings abound, but most Americans see this as a sign of progress

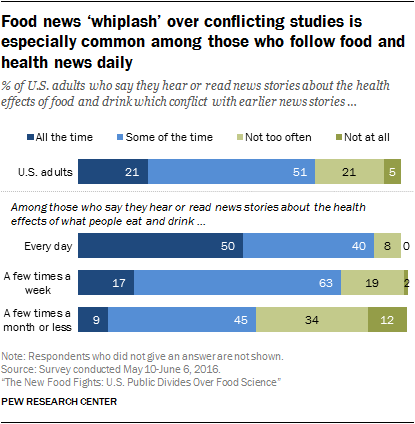

A clear sign that many Americans are thinking about food is that they are paying attention to news and research studies on the subject. Fully two-thirds (66%) of the public says they hear or read news stories about the health effects of what people eat and drink every day (23%) or a few times a week (43%). About one-quarter (24%) say they see these news stories a few times a month while 9% report seeing these stories less often than that.

And many Americans perceive such studies as contradicting prior news reports at least some of the time. About half of U.S. adults (51%) say they hear or read news stories about the health effects of foods that conflict with earlier studies some of the time and roughly one-in-five (21%) say this occurs all the time. A minority of Americans (26%) say this does not occur at all or not too often.

People who regularly follow news about food and health issues are particularly likely to see news stories with contradictory findings. Some 50% of Americans who follow news about the health effects of foods on a daily basis say they see conflicting news reports about food all the time. Just 17% of those who hear or read food news a few times a week say that conflicting stories about the health effects of food and drink occur all the time and 9% of people who less regularly attend to food news say conflicting reports occur all the time.

There is considerable concern in the science community that this whiplash effect might confuse Americans and affect their views of the trustworthiness of science findings. The survey included two questions to shed light on how the public makes sense of contradictory findings about the health effects of foods.

A majority of the American public (61%) says “new research is constantly improving our understanding about the health effects of what people eat and drink, so it makes sense that these findings conflict with prior studies,” while a 37% minority says “research about the health effects of what people eat and drink cannot really be trusted because so many studies conflict with each other.”

People’s focus on food issues is not strongly related to beliefs about news stories with conflicting findings. Instead, people’s general levels of knowledge about science, based on a nine-item index, tie to how people make sense of conflicting food studies in the news. Some 74% of those high in science knowledge say studies with findings that conflict with prior studies are signs that new research is constantly improving. But those in low science knowledge are closely divided over whether such studies are signs of improving research (46%) or show that food research cannot really be trusted (50%).

And, fully 72% of U.S. adults say even though new studies sometimes conflict with prior findings “the core ideas about how to eat healthy are pretty well understood.” Only one-quarter of the public (25%) feels overwhelmed by the inconsistent findings, saying, “It is difficult to know how to eat healthy because there is so much conflicting information.”

Here, too, beliefs are closely linked with people’s level of knowledge about science. Fully 92% of those high in science knowledge say the core ideas about how to eat healthy are pretty well understood as do 78% of those with medium science knowledge. But those low in science knowledge are closely split with half (50%) saying the core ideas of how to eat healthy are pretty well understood and 47% saying it is difficult to know how to eat healthy because there is so much conflicting information. Thus, Americans with less grounding in science information appear to be more confused by and distrustful of research with contradictory findings about food and health effects.