A person’s age is one of the most valuable and informative demographic characteristics available to those who study public opinion. Age is many things at once: It places a person in the biological arc from birth to death; it roughly corresponds with where they are in the life cycle of social roles and responsibilities; and it situates each of us as a member of a group born around the same time, who experience the real world together as time passes. All three of these ways of thinking about age are potentially useful to those who study social behavior.

Unlike religious affiliation, race or gender, age is relatively easy to measure. Some organizations ask for the respondent’s current age, while others ask for year of birth.

We do both, depending on the survey situation. Year of birth is our preferred method for the American Trends Panel, since we typically retain panelists for many years and their birth year does not change. Still, relying only on age or year of birth collected once a year means that a panelist’s age is updated at an arbitrary point in the year (at the time of our annual data collection) rather than on their birthday, and so their age is inaccurate for part of the year. The most useful and accurate measure of age would be a person’s actual birth date, but we stopped asking this question several years ago as privacy concerns were becoming more widespread.

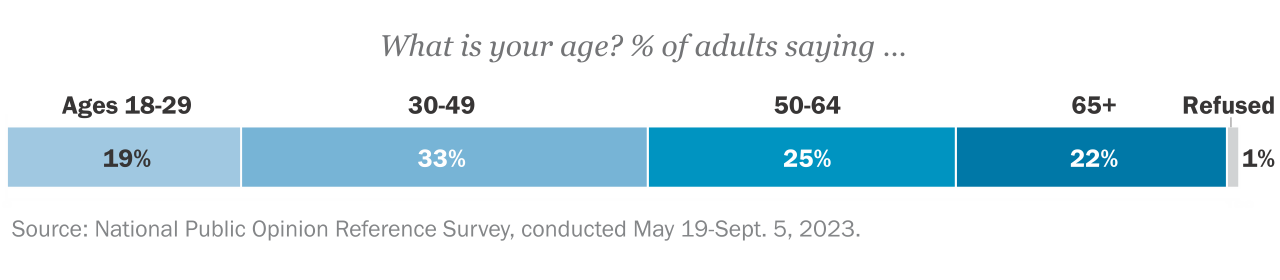

While measuring a person’s age is straightforward, it is a personal characteristic and is sensitive for some people. In our national demographic survey in 2023, 1.5% of respondents refused to state their age. Nonresponse on this question arises from both a cultural belief that one’s age is a private matter and from modern concerns about privacy and potential identity theft. Among members of the American Trends Panel, however, nonresponse on year of birth is extremely low – less than 0.5%.

Using age to understand public opinion

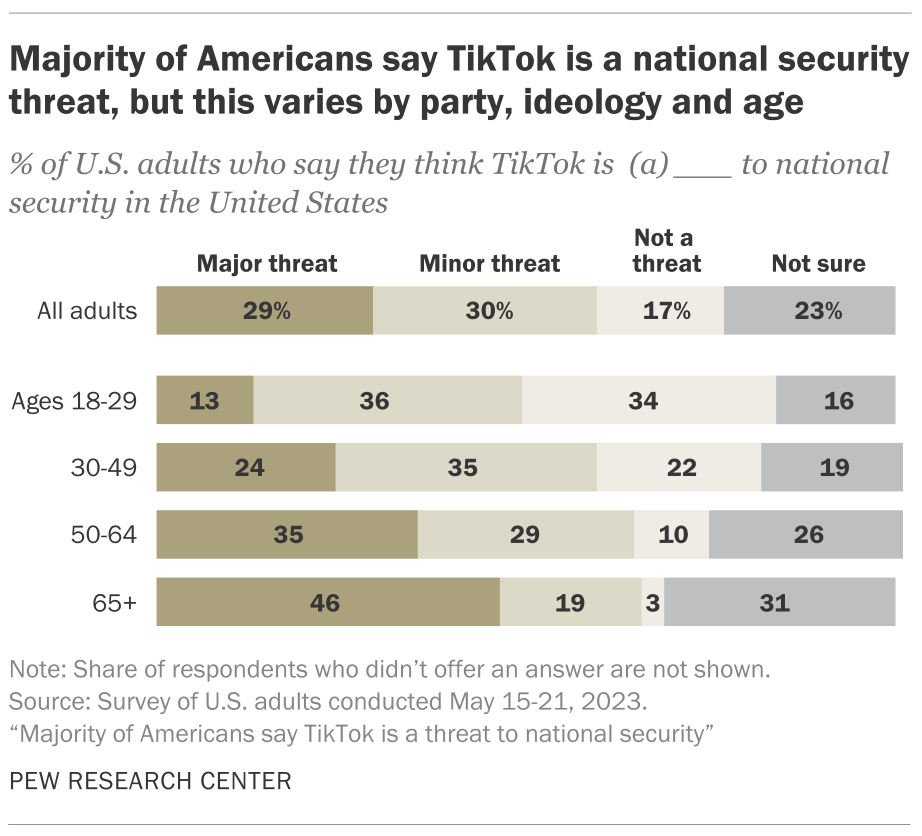

When we want to compare the opinions of older and younger people on some topic, we typically use a set of categories that break up the sample into age brackets. The choice of cut points for the categories is somewhat arbitrary, but it is common in survey analysis to see groups like “younger than 30” and “65 and older.” The categories are determined both by the needs of the analysis (e.g., if we want to compare retirement-age people with others) and by whether a group will have a sufficiently large sample (e.g., there is interest in data about adults of college age, such as those 18 to 22, but most survey samples will not have enough respondents in this age group for reliable analysis).

Age and generation

A person’s age tells us not only where they fall in the life cycle but also what historical circumstances they have lived through. People sometimes bear the imprint of these circumstances – especially those that occurred around the time of adolescence – many years later.

“A person’s age tells us not only where they fall in the life cycle but also what historical circumstances they have lived through.”

A group of people who share a set of birth years is called an age cohort. Sometimes age cohorts are given labels and referred to as generations. For example, these days it’s pretty hard to avoid references to Millennials and Gen Z.

While generational analysis is highly popular, the drawing of generational lines is fairly arbitrary. One of the clearest was the post-World War II Baby Boom generation, who have been a distinctive and consequential part of the population since they first appeared with a surge in births in 1946. Demographers consider the end of the Baby Boom generation to have been 1964, when the birth control pill became widely available and the demographic bulge was fading.

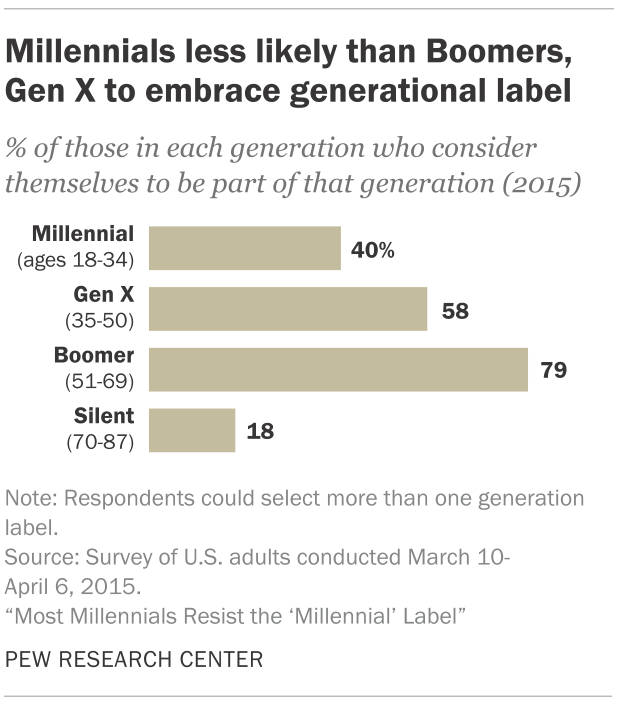

The dividing lines for more recent cohorts are less clear. Perhaps the best-known generational grouping after the Baby Boomers are the Millennials, a label popularized by the authors Neil Howe and William Strauss. But in a survey we conducted in 2015, only 40% of adults categorized as Millennials (ages 18 to 34 at the time) considered themselves to be a part of the Millennial generation. Even those in Gen X were more likely to embrace their label.

While the idea that powerful experiences during adolescence can leave a distinctive mark on people is generally accepted, there are widespread concerns among scholars that the kinds of generational groupings commonly used in marketing and popular culture are often not scientifically sound. In response to such concerns, we’ve modified how we will use the idea of generations in ongoing and future research.

Related: How Pew Research Center will report on generations moving forward

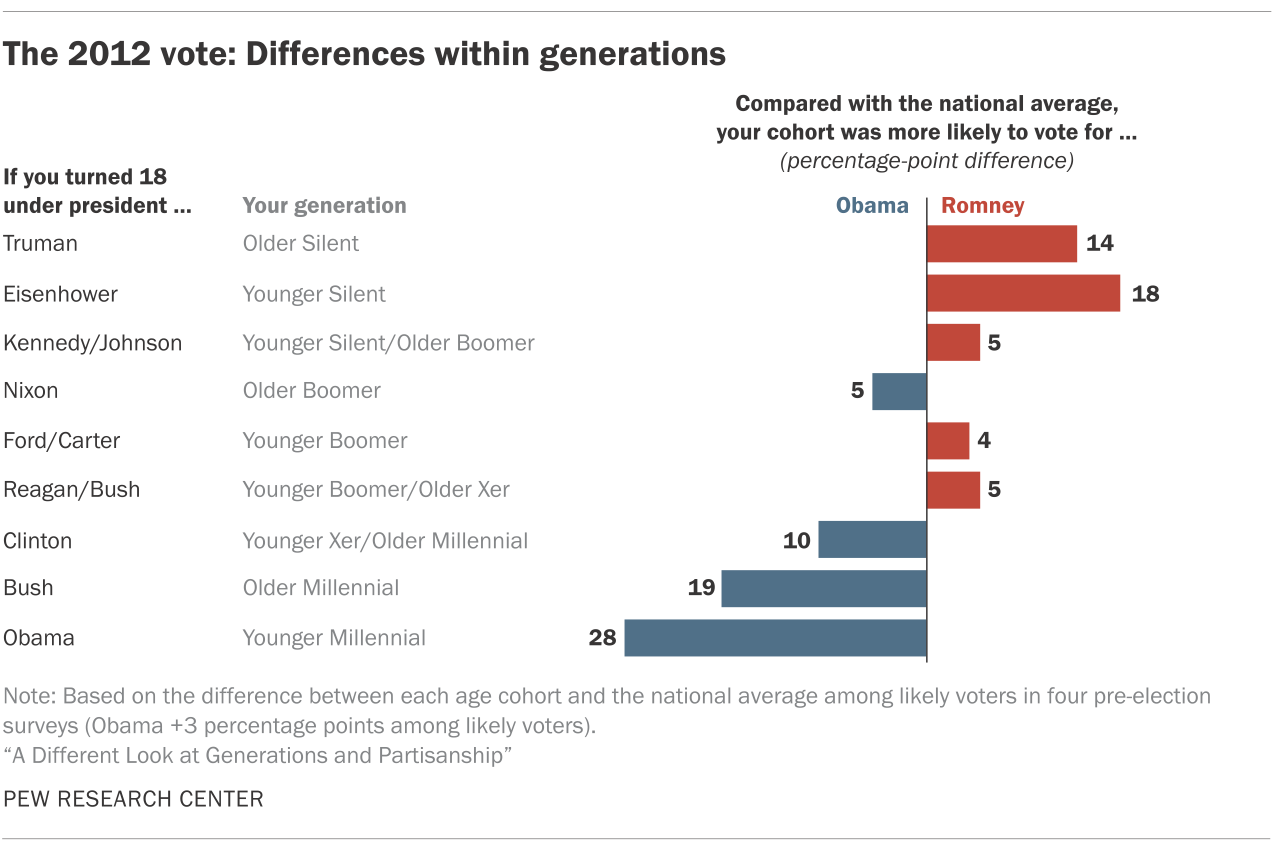

One example of a different approach was a 2015 Center study that defined age cohorts by who was president when the individuals turned 18. It found that those who reached this age milestone when Richard Nixon was president tended to vote more Democratic than those on either side of them chronologically. The theory is that people who first formed their political identity during the time of a disgraced Republican president were more supportive of the Democratic Party than those who formed their identity during the presidential terms of relatively unpopular Democrats (Lyndon Johnson and Jimmy Carter).