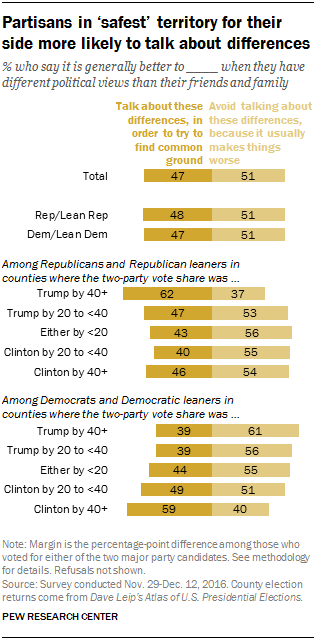

In the wake of the 2016 election, Republicans and Democrats who live in the “safest” counties politically – those that their party’s presidential candidate won by overwhelming margins – expressed more willingness to address political differences in conversation than did partisans living in counties where the vote was more competitive.

At the national level, there was almost no difference in these views between Republicans and Republican-leaning independents and Democrats and Democratic leaners. About half of Republicans and Democrats (51% of each) said it was better to avoid talking about political differences, while nearly as many said it was better to address differences to try to find common ground.

But a new analysis of Pew Research Center survey data collected in fall 2016, along with county-level election data, finds that partisans living in counties in which their party was politically dominant that year were much more likely to support seeking common ground when it comes to political differences than were those who lived in politically mixed places, or in which the other party was dominant.

A majority (62%) of Republicans and Republican leaners in counties that went very strongly for Donald Trump in the general election (those where his share of the two-party vote was at least 40 percentage points greater than Hillary Clinton’s) said that when these disagreements happened, it was better to try to find common ground. In counties that Trump won less resoundingly, or those where Clinton prevailed, Republicans were less likely to seek common ground on politics and more likely to prefer to avoid talking about differences, according to the national survey conducted Nov. 29-Dec. 12 among 4,138 adults on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel.

A similar pattern was evident among Democrats and Democratic leaners: 59% of those living in counties where Clinton defeated Trump by 40 points or more said it was better to address political differences, while 40% it was better to avoid talking about these differences.

Among Democrats in strong Trump counties, opinion was almost the reverse: 61% said it was better to avoid raising political differences while just 39% said it was better to talk about them.

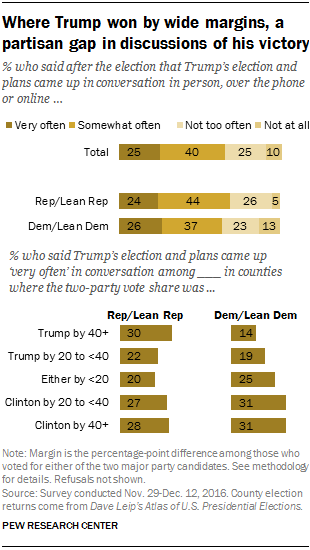

The post-election survey found only modest partisan differences in how often people talked about Trump’s plans and policies in conversations in the weeks after the election.

But the geographic pattern was different for Republicans than for Democrats in counties where one side or the other dominated. In counties that went strongly for Trump, 30% of Republicans and just 14% of Democrats said the president-elect’s plans came up “a lot” in conversation. Partisan differences were more modest in other counties. And in those counties where Clinton won decisively, 31% of Democrats and a similar share of Republicans (28%) said this topic came up a lot.

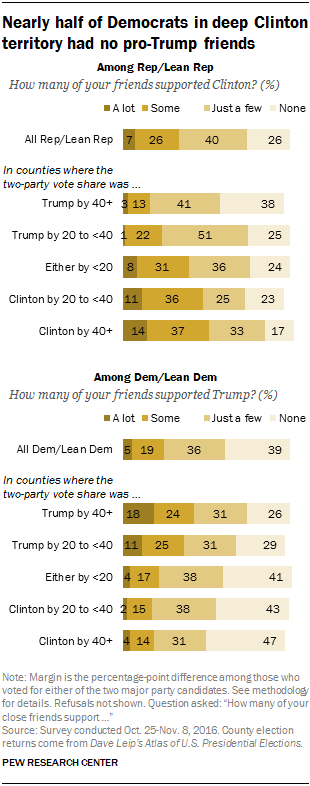

Cross-party friendships less common in the safest counties

The political makeup of Americans’ friend networks is also associated with where they live. Partisans in counties where the vote was lopsided in favor of their party’s candidate were more likely than those in more competitive counties to say they had no friends who backed the opposing candidate.

In a separate survey conducted just before the 2016 election, 23% of all Democrats and Democratic leaners said they had at least some friends who backed Trump, 36% said “just a few” supported him and 39% said they had no friends who backed the GOP candidate.

But nearly half of Democrats (47%) in counties that went very strongly for Clinton said they had no friends who supported Trump. By contrast, in places that Trump won by substantial margins, no more than a third of Democrats said they had no friends backing Trump.

A similar pattern is evident among Republicans, though overall, a greater share of Republicans (33%) said they had at least some friends who backed Clinton. Another 40% said they had just a few friends who supported her, while 26% said they had no friends who backed Clinton.

Among Republicans living in counties that voted strongly for Trump, 38% said they had no friends who supported Clinton. As with Democrats, Republicans in counties with a greater share of Clinton voters were less likely to say they had no friends who backed Clinton.

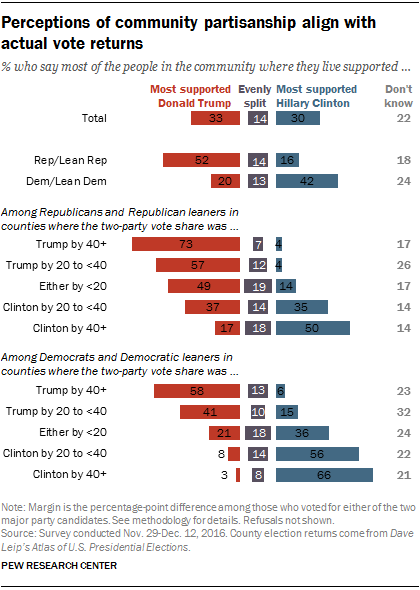

People have a good sense of how their community voted

There is a strong relationship between people’s perceptions of support for Trump or Clinton in their local community and the actual result of the two-party vote in their county. (Note: These measures may also differ somewhat because the voting pattern of the larger county one lives in and the voting patterns of one’s community may not correspond.)

About half of Republicans and Republican leaners (52%) said they lived in areas where most of their neighbors supported Trump, while 42% of Democrats and Democratic leaners said they lived in areas that mostly supported Clinton. Republicans who live in counties that voted overwhelmingly for Trump were much more likely than those who lived in areas that mostly supported Clinton to say that most of their neighbors supported Trump (73% in counties that voted strongly for Trump versus 17% in counties that voted strongly for Clinton).

Perceptions of how one’s community voted and the actual county-level vote share may differ either because a person misperceives their community, or because their “community” vote and their county-level vote may not be the same thing.

To provide one example, while Hennepin County, Minnesota (just outside of Minneapolis) voted for Clinton by a wide margin in the 2016 election, individual areas of the county voted for Trump by a wide margin.

Note: See full methodology here (PDF).