As it marks its 80th year, the United Nations is facing a major budget shortfall. The situation could worsen as the United States – the UN’s largest funder and debtor – reassesses its ties to the organization.

The U.S. recently left several UN agencies, including the World Health Organization and Human Rights Council, and plans to withdraw from UNESCO by the end of next year. In mid-July, Congress passed the Trump administration’s rescissions package, pulling back about $1 billion of previously approved UN funding. And further cuts may be forthcoming: The administration’s budget for fiscal year 2026 proposed ending UN peacekeeping payments and pausing most other UN contributions.

The UN has responded to its budget crunch by curbing program spending, freezing hiring and launching a longer-term efficiency initiative. It’s also dipped into its reserve accounts five times since July 2019, borrowing a record $607 million in 2024. But the UN’s financial viability largely depends on how – and whether – the U.S. decides to support the organization moving forward.

Read on for answers to some common questions about the UN and its funding:

- How is the UN funded?

- How much do the U.S. and other countries have to pay?

- How have dues changed over time?

- Do members always pay their dues?

- What happens to members that don’t pay their dues?

- How do Americans view the UN?

How is the UN funded?

The organization is primarily funded by its 193 member states through mandatory assessed contributions. The UN requires separate contributions for its two main budgets:

- The regular budget, which finances core organizational activities that the General Assembly approves, including those related to economic and social development, disarmament projects, and human rights issues

- The peacekeeping operations budget, which finances most UN peacekeeping missions and several service centers worldwide

The regular budget applies to each calendar year, while the peacekeeping budget covers each fiscal year, which runs from July 1 to June 30.

Other assessed contributions fund the organization’s international tribunals and special projects, such as the renovation of the UN headquarters in New York City.

In addition, the UN operates many funds and programs, such as the World Food Program and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), that are exclusively financed through voluntary contributions from member states.

Related: What the data says about U.S. foreign aid

How much do the U.S. and other countries have to pay?

The amount each member must pay annually varies based on its relative “capacity to pay.” The UN uses a formula – which accounts for the country’s gross national income, population size and external debt, among other factors – to establish the “scale of assessments” for the regular budget. The scale ranges from 0.001% of the budget to 22%, but contributions for the least developed countries are capped at 0.01%.

The scale for the peacekeeping budget follows the same system, but those rates are adjusted, with the five permanent member states of the Security Council – China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the U.S. – bearing the brunt of the cost.

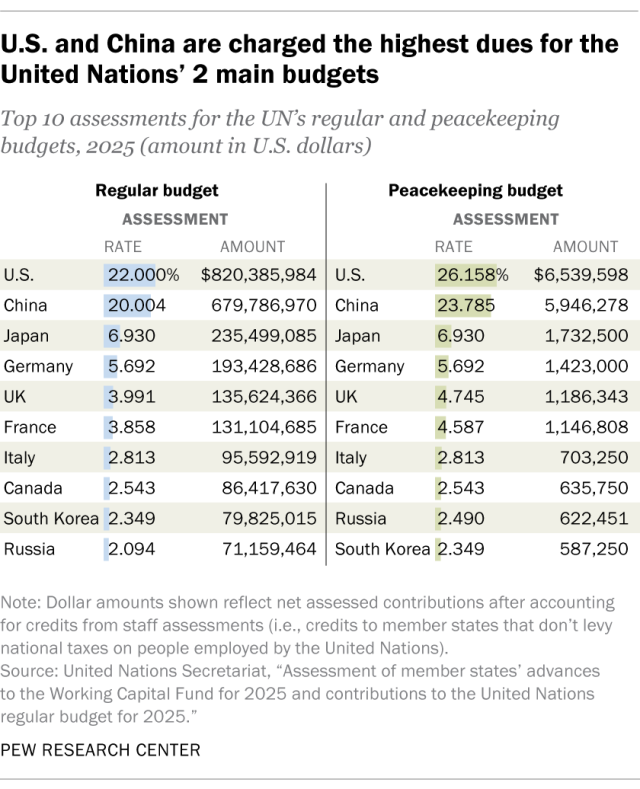

As the world’s largest economy, the U.S. has always been assessed at the maximum rate. This year, it was responsible for 22% of the UN’s regular budget assessments, or $820.4 million of the $3.5 billion net total.

China was responsible for paying the next-largest share (20.004%, or $679.8 million). Japan was a distant third at 6.930% ($235.5 million).

On the other hand, 175 of the 193 member states were each responsible for less than 1% of the UN’s regular budget in 2025. This includes 28 states assessed at the minimum 0.001% rate.

The U.S. was also assessed at the highest rate for the UN peacekeeping budget in 2025 (26.158%, or $6.5 million of the $25 million total). China (23.785%, or $5.9 million) and Japan (6.930%, or $1.7 million) again had the next-highest assessments.

How have dues changed over time?

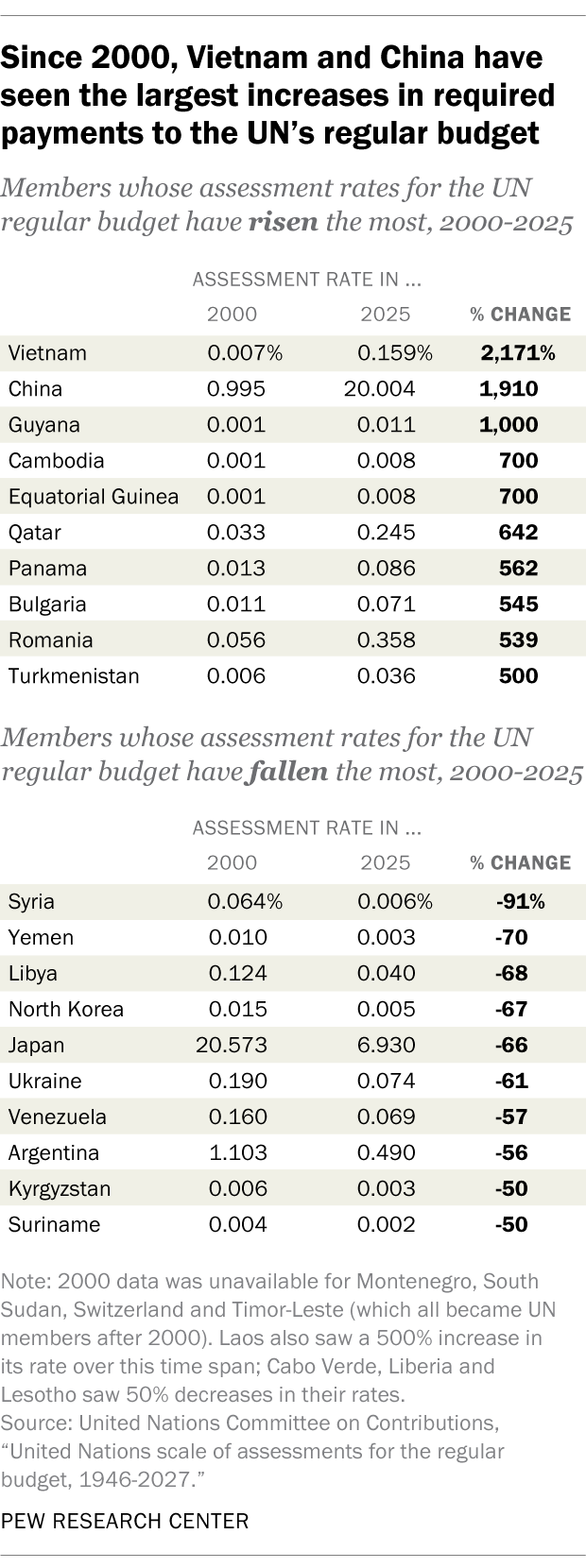

Looking at just the regular budget, assessment rates have increased for the majority of states that have been UN members since 2000 (116 of 189). Vietnam, China and Guyana saw the largest increases. Meanwhile, rates stayed the same for 33 members and decreased for 40.

(Montenegro, South Sudan, Switzerland and Timor-Leste are excluded from these calculations. They became members after 2000, but their rates have remained relatively consistent – and low – since joining.)

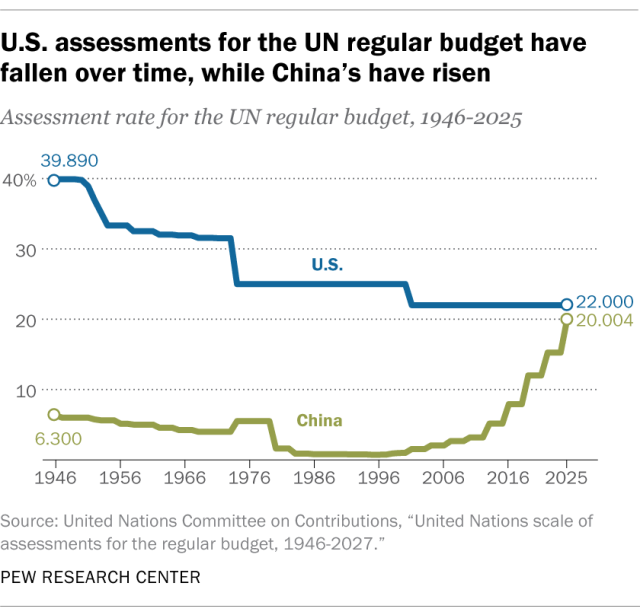

The United States’ regular budget assessment rate was much higher in the earliest years of the UN’s existence: 39.890% in the late 1940s. It stood at 25% from 1974 until 2001, after the UN lowered the cap to 22%. America’s rate has remained 22% ever since.

Meanwhile, the rate for China – the world’s second-largest economy – has grown significantly. It was initially around 6%, but it started to fall in the 1950s and was under 1% for most of the ’80s and ’90s. It grew slowly in the early 2000s before climbing more rapidly to its current 20.004%.

Do members always pay their dues?

Contributions are due within 30 days of assessment notice from the UN Secretary General, usually around early or mid-February for the regular budget. But the UN has long struggled to get members – especially the U.S. – to pay their contributions on time, or at all.

No more than 53 of the 193 member states have paid their regular budget contributions on time each year since 2019 (the earliest year with detailed data available). And within the last two decades, the UN has never received full contributions from all members.

Member states might withhold both regular budget and peacekeeping contributions for many reasons, including differences between national and UN fiscal calendars, financial constraints, or political objections to UN program goals or resolutions.

Historically, the greatest number of members pay their regular budget dues within the first few months of the year. The UN often sees a small spike in payments in September, but contributions otherwise trickle in slowly throughout the year.

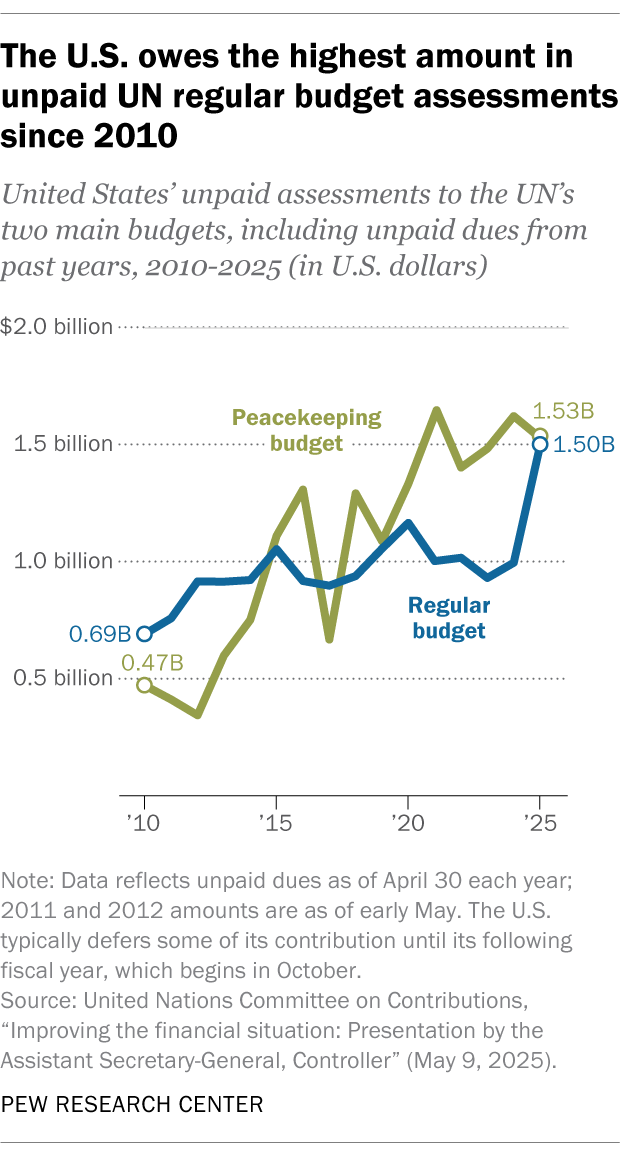

The U.S. typically defers some of its contribution until its following fiscal year, which begins in October. This practice began in the 1980s, partially in response to America’s growing deficit.

As of April 30, 92 UN members have not paid their full regular budget assessments for 2025, according to the latest detailed data from the UN.

Including unpaid dues from previous years, the U.S. ($1.5 billion), China ($597 million), Russia ($72 million), Saudi Arabia ($42 million), Mexico ($38 million) and Venezuela ($38 million) have the largest outstanding regular budget balances as of April 30.

This is the sixth time since 2015 that the United States’ unpaid regular budget assessments totaled over $1 billion in April of each year. (As noted earlier, the U.S. typically defers many payments until its new fiscal year in October.)

Many UN members (130) have also not made their full 2025 peacekeeping contributions as of April 30. Including unpaid dues from previous years, the U.S. owes $1.5 billion. That’s partly because Congress has often capped peacekeeping spending at 25% since the mid-1990s, but the UN continues to assess the U.S. share of that budget at a higher rate.

China ($587 million), Russia ($123 million) and Venezuela ($93 million) owe the next-largest amounts in peacekeeping dues.

What happens to members that don’t pay their dues?

Any dues that aren’t paid by Jan. 1 of the following fiscal year are considered “arrears.” If a member’s arrears equal or exceed the amount of contributions owed for the previous two years, the member can lose its vote in the General Assembly.

Afghanistan, Bolivia, Sao Tome and Principe, and Venezuela currently meet these criteria. But the General Assembly allowed Sao Tome and Principe to continue voting until the 79th session ends this coming September, concluding that the small island nation was unable to pay for reasons outside of its control.

How do Americans view the UN?

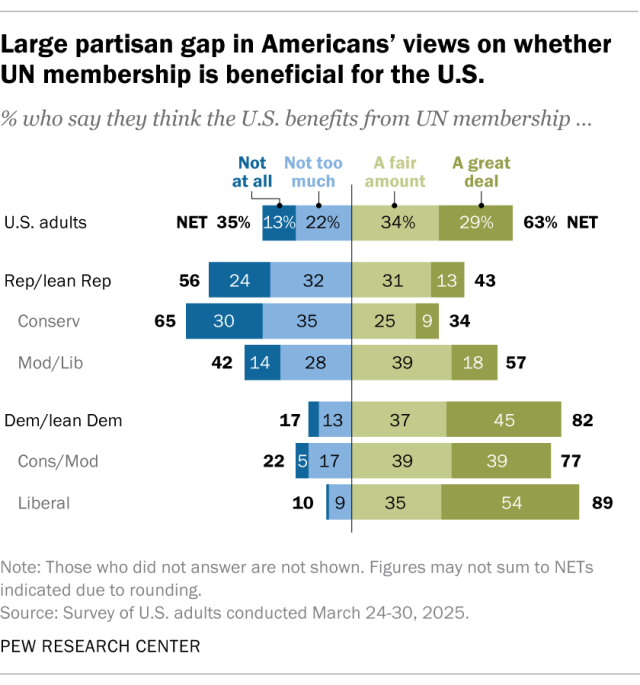

Many Americans (63%) say they think the U.S. benefits from UN membership a great deal or fair amount, according to a Pew Research Center survey from March. The share who say this has risen slightly since last spring (up 3 percentage points). However, views differ widely by party.

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are about twice as likely as Republicans and GOP leaners to say that the country benefits from UN membership (82% vs. 43%). More Republicans instead take the opposite view: 56% don’t think the U.S. benefits much or at all, including 65% of conservative Republicans.

More broadly, a 57% majority of U.S. adults express a favorable view of the UN – up 5 points since spring 2024. While Democrats have become more likely to see the UN positively over this time span, Republicans’ views remain statistically unchanged.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.