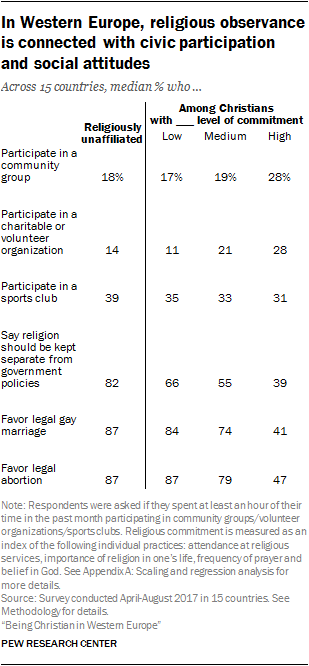

Overall, fewer than half of respondents across Western Europe regularly take part in civic activities, such as participating in a performing arts group, charitable organization, church or religious group, sports club or any other community group or association. Across many of these activities, there is a clear link between religious observance and civic participation: Highly observant Christians are more likely than either Christians with lower levels of observance or religiously unaffiliated adults to participate not only in religious groups but also in charitable or volunteer organizations and other community groups. This suggests that active participation in a religious community, not just religious identity or belief alone, may be associated with higher rates of civic participation.22

But, although highly committed Christians are generally more civically engaged than other Europeans, they are not more engaged in every kind of activity. When it comes to sports clubs or recreation groups, religiously unaffiliated adults and Christians with lower levels of religious commitment are more likely than highly committed Christians to participate.

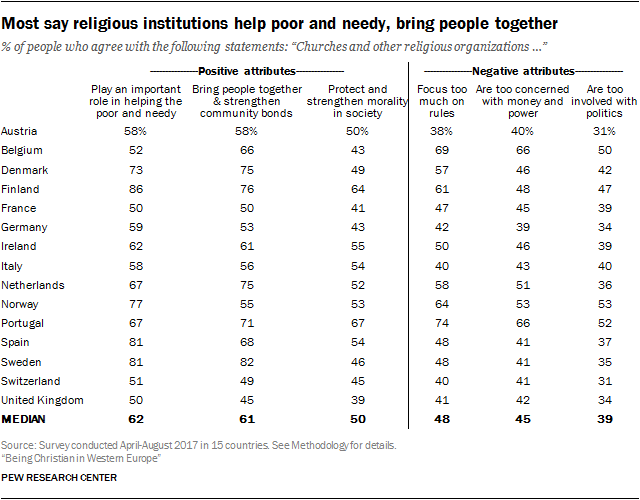

Still, religious observance is tied to overall civic engagement, and many Western Europeans also see churches and religious institutions as having positive impacts on society. Majorities across the region say that religious institutions bring people together, strengthen community bonds and play an important role in helping the poor and needy.

Fewer, although still considerable shares, also agree with a series of negative statements about religious institutions. For example, in Portugal – the most religious country surveyed, by several measures – majorities say churches and other religious institutions focus too much on rules (74%) and are too concerned with money and power (66%).

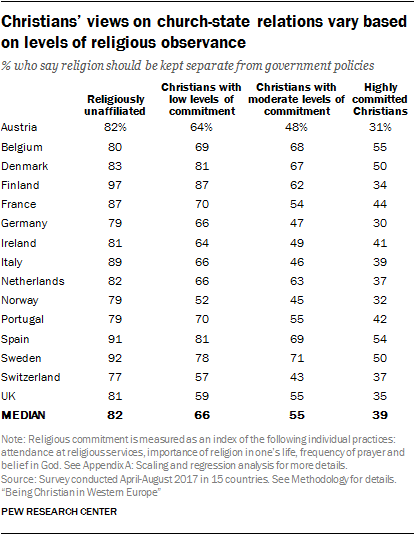

In addition, Western Europeans generally favor keeping religion separate from government. Christians who show low levels of religious commitment are more supportive of separation of church and state than are highly observant Christians. But even compared with Christians who show low levels of religious commitment, religiously unaffiliated adults are especially likely to say religion should be kept separate from government policy.

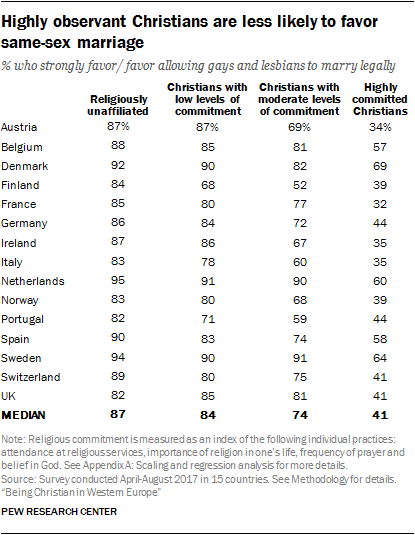

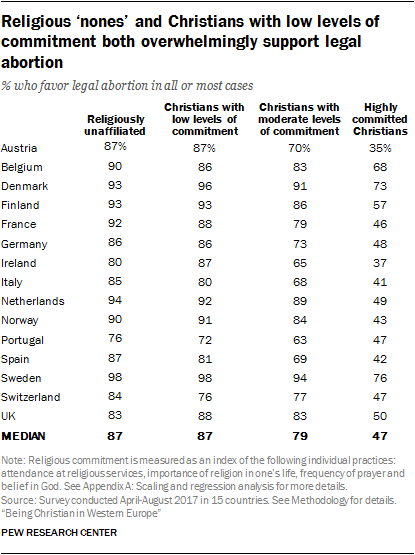

There is less of a divide between “nones” and Christians with low levels of commitment when it comes to attitudes on gay marriage and abortion. Both religiously unaffiliated adults and Christians with low levels of religious observance overwhelmingly favor legal gay marriage and abortion. Highly observant Christians, meanwhile, are less likely to take these positions.

Most people say they do not spend time participating in civic groups

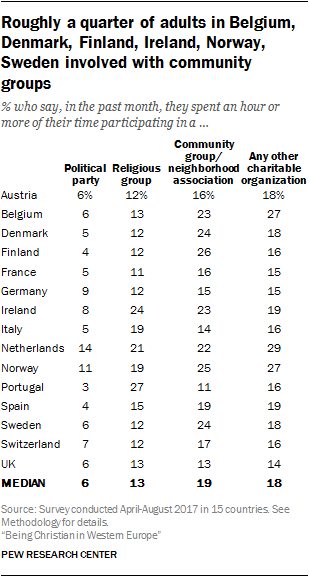

Generally, most Western Europeans say they have not spent an hour or more of their time in the past month participating in a civic organization such as a political party, religious group, charitable organization or community group, although roughly a quarter of adults in Portugal (27%) and Ireland

(24%), and about one-in-five in the Netherlands (21%) say they have spent at least an hour of their time volunteering with a religious organization.

In some countries, sizable minorities say they participate in a community organization or neighborhood association. This includes about a quarter of adults in Finland (26%), Norway (25%), Denmark (24%), Sweden (24%), Belgium (23%) and Ireland (23%). There are similar levels of participation in other kinds of charitable organizations: About three-in-ten Dutch adults (29%) reported doing this in the past month at the time the survey was conducted.

Volunteering with a political party is less common: In nearly every country surveyed, roughly one-in-ten or fewer report spending an hour or more of their time in the past month working with a political party.

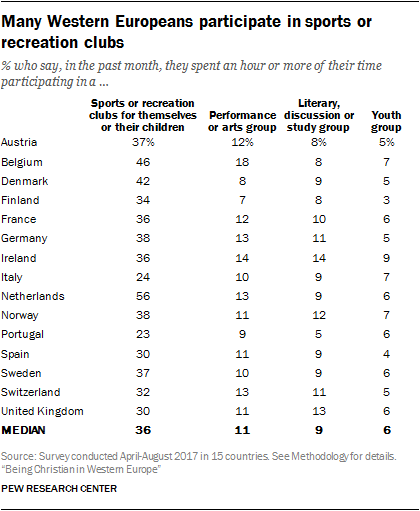

In addition to asking about volunteering with civic or charitable organizations, the survey also asked people if they had spent an hour or more of their time in the past month participating in recreational groups such as a sports club for themselves or their children, a performance or arts group (such as a choir or theater group), a literary discussion or study group (such as a book club), or a youth group (such as Scouts).

Of these activities, sports or recreational clubs appear to be the most popular. About a third or more of adults surveyed in most countries report that they recently participated in a sports or recreation club, including a majority of respondents in the Netherlands (56%). By contrast, medians of about one-in-ten people participate in performance or arts groups or in literary, discussion, or study groups. Even fewer adults participate in youth groups.

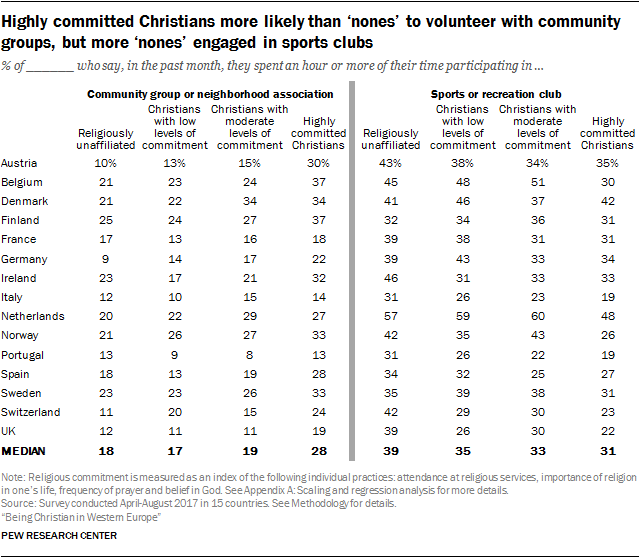

On the whole, highly observant Christians are more likely than less observant Christians and “nones” to be civically engaged. For example, highly committed Christians are more likely than others to be involved not only in religious groups, but also in charitable or volunteer organizations as well as community groups.

But highly committed Christians are less likely than unaffiliated respondents to participate in sports teams or recreational clubs, suggesting that for some nonreligious people in Europe, sports clubs could replace religious groups as a form of community engagement.23 For example, in the UK, 22% of highly committed Christians say they are part of a sports or recreational club, compared with 39% of “nones.”

On balance, highly committed Christians are about as likely as “nones” or Christians with lower levels of commitment to be involved with literary discussion groups, such as book clubs.

Adults under 35 are less likely than older people to be involved in civic groups such as community or charitable organizations, but they are more likely to say they have spent an hour or more of their time with a sports club. And higher shares of college graduates than of adults with less education say they are involved in performing arts, community, sports, volunteer or literary discussion groups.

But even after controlling for age, gender and education, highly committed Christians are significantly more likely than those with lower levels of commitment and religiously unaffiliated adults to be involved in a wide range of community organizations. Conversely, religiously unaffiliated adults and Christians with low levels of commitment are more likely than highly committed Christians to be involved in sports clubs, even when holding other demographic factors constant.

Measuring religious commitment

In this chapter, religious commitment is measured on a scale combining four different measures: How important a person considers religion in their lives, how often they attend religious services, how often they pray and whether they believe in God. Christian respondents are classified as high, medium or low in their religious commitment based on their scores on the scale. See Chapter 3 or Appendix A for additional details on the scale.

Substituting the commitment scale with a simpler measure that uses attendance at religious services to classify Christians into churchgoing (that is, those who attend church at least monthly) and non-practicing (those who attend church no more than a few times a year) does not change the overall patterns described in this chapter.

Many in Western Europe say churches have positive impacts on society

Most Western Europeans see churches and other religious institutions as having a positive role in their societies. Solid majorities in most countries agree that churches and other religious organizations “play an important role in helping the poor and needy” and that they “bring people together and strengthen community bonds.” And in several countries surveyed, roughly half or more of respondents say they agree churches and other religious organizations “protect and strengthen morality in society.”

The survey also asked whether people agree with three negative statements about churches and other religious institutions. On balance, more respondents agree with the positive statements than with the negative ones. For example, fewer than half of Germans say churches focus too much on rules (42%), are too concerned with money and power (39%), or are too involved with politics (34%).

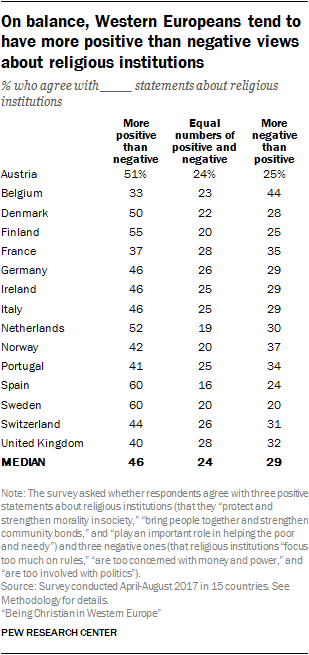

Looked at another way, a median of 46% of Western Europeans agree with more of the positive statements about organized religion, compared with a median of 29% who agree with more of the negative statements. Others (median of 24%) agree with equal numbers of positive and negative statements about organized religion.

Only in Belgium is the share of people with a predominantly negative view of religious institutions (44%) larger than the share with a mainly positive opinion (33%). In France, these two figures are roughly equal (37% mostly positive, 35% mostly negative).

On the whole, people over 35 are generally more likely than younger adults to take positive views of religious institutions. The Netherlands is an exception to this pattern: Older Dutch people are less likely than young Dutch adults to have positive views of religious institutions.

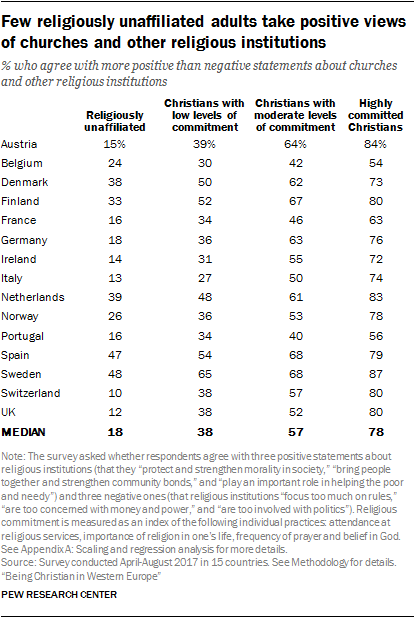

Among Western Europeans, opinions about religious institutions follow a consistent pattern based on religious identity and observance. Highly committed Christians are most likely to express positive views of religious institutions, while “nones” are least likely to do so. Christians who display low and moderate levels of religious observance fall between these two extremes.

To give one example, more than eight-in-ten Austrian Christians with high levels of religious commitment agree with more positive than negative statements about religious institutions (84%). Among moderately observant Christians in Austria, 64% share this view. But fewer than half of low-observance Christians (39%) express more positive than negative views of churches, as do just 15% of “nones” in Austria.

The role of Christianity and churches in Europe

While survey results show that Western Europeans tend to express positive views of churches and other religious organizations, focus groups in five countries revealed further insights into how adults think about the ways religious institutions and the broader society should interact.

Both sets of focus groups – those composed entirely of Christians and those made up entirely of religiously unaffiliated adults — acknowledged their societies’ Christian roots in a generally positive way. Participants in both kinds of groups felt that Christianity, while not perfect, provides a foundation of basic values and ethics that is valuable. Participants said Christianity can give children a moral framework as they mature, helping them become good citizens. (According to the survey, roughly half of Western Europeans feel that the religious institutions in their country protect and strengthen morality in society.)

“I think I’d agree completely that [the UK] does seem socially to be pretty secular, but I guess historically and institutionally it’s Church of England, Christianity.”

– 27-year-old atheist woman, United Kingdom

“[Our country] is Christian. I see it as a Christian ground. If we look at everything from the justice system, the law book to the practice within health care … it is all built on Christian values. … When I read magazines and talk to people, I still assume a Christian ground.”

– 39-year old atheist man, Sweden

“I think [going to church] provides a good moral compass. It does teach you right and wrong. … You take that throughout your life. I learnt quite a lot, I took quite a lot from Sunday school. … When you go at a young age, I think it does make a big difference.”

– 39-year-old Christian man, United Kingdom

“Maybe I made a mistake not to get [my children] baptized. I notice today that they lack the roots of our civilization. They don’t have the culture they should have, because they did not follow this course. Not that it is baptism that gives it, but it’s among other things religious education gives to children. This Bible, and especially the Old Testament, is extremely rich and brings all the roots of our civilization, and it is upon that that our societies were built. … I hope that they will find [this] out when they are adults.”

– 57-year-old “nothing in particular” man, France

“Although there are many people that may say they don’t believe, they do learn about [religion]. In the end, religion instils values that get passed on to individuals. And I believe that in the end, whether they believe or not, have been educated in religion or not, the values are very similar.”

– 31-year old Christian man, Spain

At the same time, the focus group discussions on Christianity’s role in society were not all positive; many participants said they disliked Christian rules or teachings that they feel have not changed with the times, such as opposition to same-sex marriage. About half of Western European adults in the survey echoed this sentiment, saying that churches and other religious institutions “focus too much on rules.”

Some adults in the focus groups discussed concerns with church teachings on abortion, gender roles and homosexuality. They said church positions on such social issues directly contradict both national attitudes and their personal sentiments on abortion and gay marriage. And despite many seeing religion as a useful moral framework, focus group participants (both Christians and “nones”) tended to want religion and government to remain separate, echoing the survey’s findings.

“I was born and raised a Catholic. … I probably lost faith when [my parents] told me they lost a child before he was christened and he wasn’t allowed a Catholic burial – completely refused from the church. So I thought that was just disgusting, so I kind of lost faith.”

– 30-year-old atheist man, United Kingdom

“You know, I think this does not fit with their philosophy: love thy neighbor, tolerance. And then they just contradict themselves like it’s nothing. I mean, to discriminate gays while telling people to love thy neighbor and to be tolerant, that just doesn’t go together, in my opinion. And that is why I thought to myself that I will not support this. That is just really phony.”

– 31-year old atheist woman, Germany

“I would say that [Christianity] supports heteronormativity in society. Above all there is a pretty outdated view of women and so on. Those are things that also inhibit the development of society.”

– 36-year old “nothing in particular” man, Sweden

“Whether the president is Catholic is not necessarily important, as long as his political agenda doesn’t favor Catholics.” – 24-year-old Christian man, France

For details on the focus groups, including locations and composition, see Methodology.

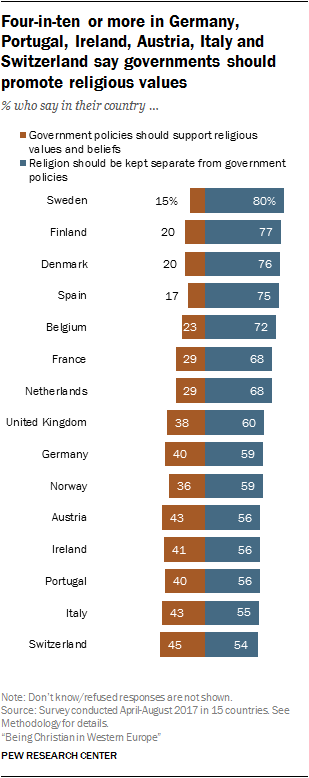

Most Western Europeans say government policies should be kept separate from religion

There is a clear consensus across most of the countries surveyed that religion should be kept separate from government policies. Still, substantial shares in several countries take the opposite view – that government policies should support religious values and beliefs in their country – including more than four-in-ten people surveyed in Switzerland (45%), Austria (43%) and Italy (43%).

People in predominantly Protestant countries are more likely than those in Catholic countries to favor separation of religion and government. A median of 76% in Protestant-majority countries say this, compared with a median of 56% in Catholic-majority countries.

Young adults (under 35) and college graduates are more likely than older people and those with less education to say religion and government should be kept separate. And men are more likely than women to say this, although majorities among both genders favor separation of church and state.

Western European “nones” are more likely than Christians, regardless of how observant they are, to favor separation of church and state. But among Christians, those with low levels of commitment are more likely than highly committed Christians to say religion and government should be kept separate.

Further statistical analysis shows that even after accounting for age, gender, education and political ideology, “nones” are more likely than low-observance Christians to favor keeping religion separate from government policy.

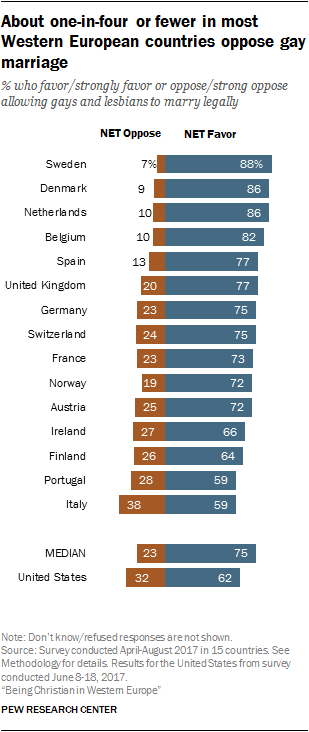

Western Europeans overwhelmingly favor legal gay marriage

Western Europeans’ preference for keeping religion and government policies separate is also reflected in their overwhelming support for legal abortion and same-sex marriage, even though these positions conflict with those of the Roman Catholic Church and some other Christian churches.

Support for same-sex marriage is highest in Sweden (88%), Denmark (86%) and the Netherlands (86%) – the first country to legalize same-sex marriage, in 2001.

Western Europeans are generally more likely than Americans to favor gay marriage, though American attitudes on the issue have shifted considerably in recent years. Currently, 62% of Americans favor legal gay marriage, compared with a median of 75% across Western Europe.

Still, some pockets of opposition remain in Western Europe. In Italy, for example, 38% of respondents oppose legal gay marriage, the highest share in the region taking that position. (Italy and Switzerland are the only countries surveyed where same-sex marriage has not been legalized, although both countries allow civil unions.24) And in several other countries, including Switzerland, roughly a quarter of the public says gays and lesbians should not be allowed to marry legally.

Christians overall are somewhat less likely than religiously unaffiliated adults to favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally. However, even among Christians, large majorities across Western Europe favor legal gay marriage.

Highly committed Christians are much less likely than Christians with lower levels of observance to favor allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry. But there is little difference between “nones” and Christians with low levels of observance in the shares who say they either favor or strongly favor allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry.

That said, religiously unaffiliated adults are more likely than Christians with low levels of observance to say they strongly favor same-sex marriage.

Adults under 35, women and people with a college education are more likely than older people, men and those with lower levels of education to favor legal same-sex marriage.

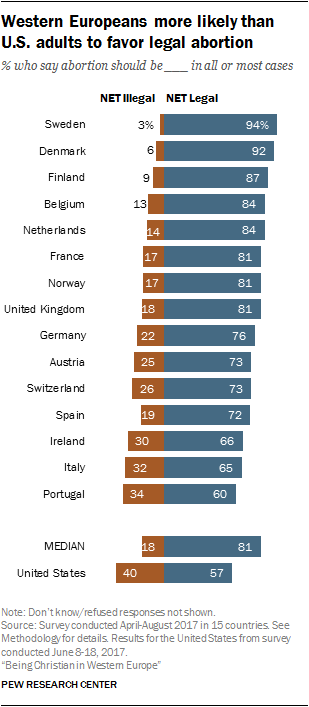

Western European adults overwhelmingly favor legal abortion

Majorities in every Western European country surveyed take liberal positions on abortion, saying they support legal abortion in all or most cases. (This also matches most abortion laws in the region.) This includes nearly nine-in-ten or more in Sweden (94%), Denmark (92%) and Finland (87%).

Western Europeans support legal abortion at considerably higher rates than do Americans. As of 2017, a slim majority of Americans (57%) say they favor legal abortion in all or most cases. By comparison, a median of 81% across Western Europe take this position.

Christians are somewhat less likely than “nones” to favor legal abortion. But even among Christians, a median of 75% across the 15 countries surveyed say abortion should be legal in all or most cases (compared with a median of 87% among religiously unaffiliated adults).

Differences among Christians on this question emerge when looking at religious commitment: Highly observant Christians are considerably less supportive of legal abortion than are less observant Christians.

“Nones” and Christians with low levels of observance have similar views on whether abortion should be legal, although religiously unaffiliated adults are more likely than Christians with low commitment to say abortion should be legal in all cases.

In addition, college graduates are more likely than others to support legal abortion. Adults under the age of 35 also are more likely than their elders to support legal abortion.

Women and men, for the most part, express similar levels of support for legal abortion – except in Norway and Portugal, where men are more likely to support it. One possible explanation for the fact that women are not more likely than men to favor legal abortion is that women tend to show higher levels of religious observance, which goes hand in hand with more opposition to abortion.