Among the many reported reasons people in the United Kingdom voted in 2016 to leave the European Union are a sense of eroding national identity and increasingly negative attitudes toward religious minorities, particularly Muslims. But on these topics, British public opinion is not outside the EU mainstream, according to a recent Pew Research Center study. In fact, in a 2017 survey that asked about these issues, the views of British adults align very closely to general opinion across the EU, even though no other country has yet voted to leave.

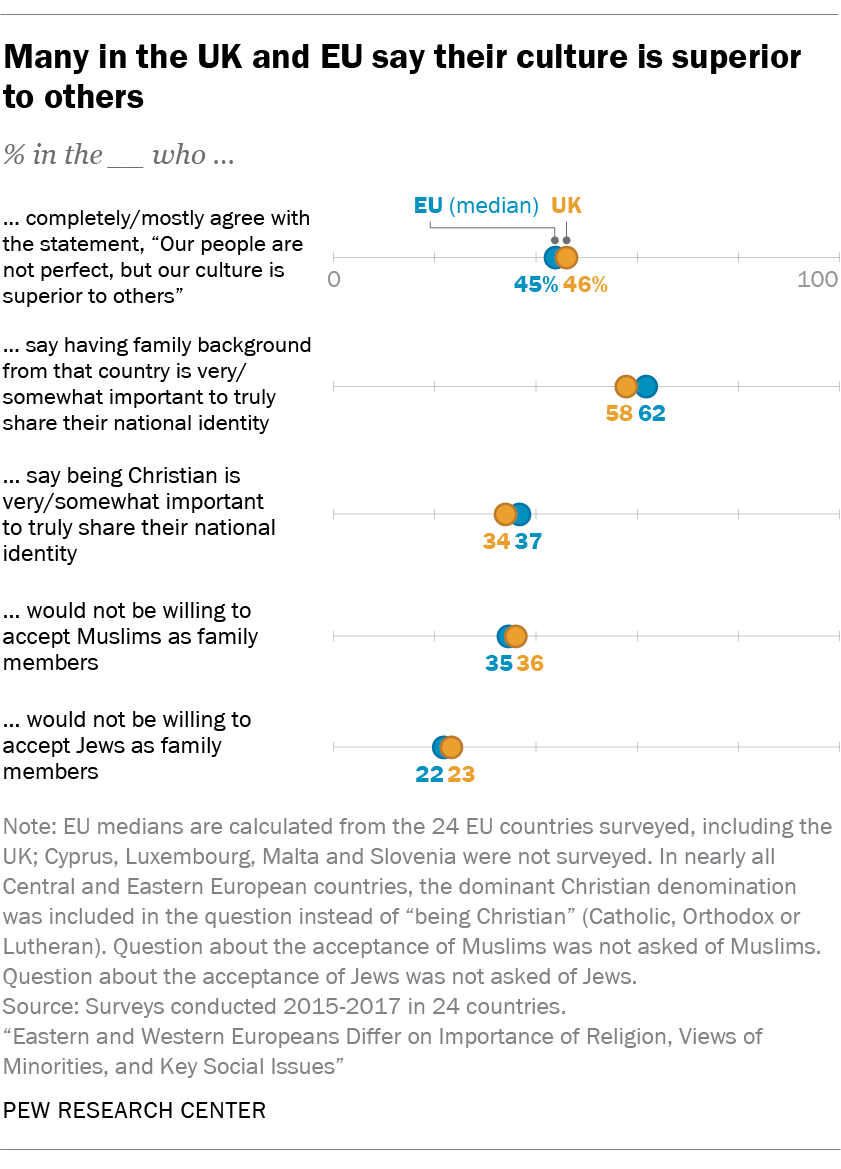

While a majority of British adults say that being born in their country and having family background from their country are important to truly share their national identity (57% and 58%, respectively), six-in-ten people across the EU also hold those views (both medians of 62%). And roughly one-third of people in both the UK and the EU would not be willing to have a Muslim family member (36% and median of 35%, respectively).

Indeed, while the British frequently are near the middle of EU opinion on some topics that featured in Brexit debates, other EU countries have much higher levels of nationalist feeling and anti-religious minority sentiment. For example, roughly eight-in-ten Czechs say they would be unwilling to have a Muslim family member (79% vs. 36% in the UK). And two-thirds of Romanians agree that, “Our people are not perfect, but our culture is superior to others” (66% vs. 46% in the UK).

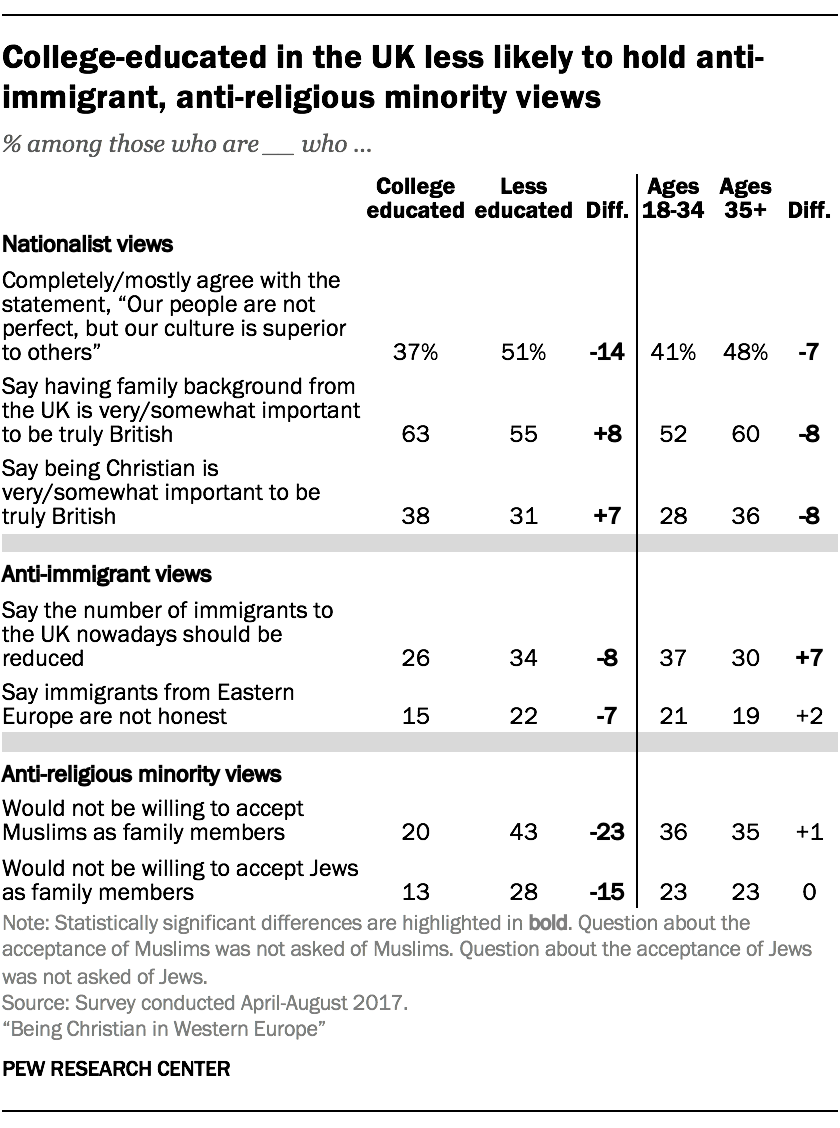

Within the UK, college-educated individuals are not as likely as those with less education to have negative attitudes toward immigrants and religious minorities. For instance, only one-in-five college-educated Britons would be unwilling to accept a Muslim family member, but about two-in-five among those with less education say this (20% vs. 43%).

However, on questions of nationalism, the educational divide is less clear. For example, those with a college education are not as likely as those with less education to agree with the notion that British culture is superior to others (37% vs. 51%). But college-educated Britons are more likely than those with less education to say having family roots in the UK is important for being truly British (63% vs. 55%).

Meanwhile, there is a clear age divide on questions of national identity and nationalism: Younger adults (those ages 18 to 34) are less likely than those who are older to agree that several factors are important to being truly British — being born in the UK, having UK ancestry or being Christian. Adults under age 35 also are less likely than older adults to agree with the idea that British culture is superior to others (41% vs. 48%).

Across the variety of topics included in this analysis, British Christians are more likely than the religiously unaffiliated (atheists, agnostics and those who identify as “nothing in particular”) to express nationalistic, anti-immigrant or anti-religious minority sentiments, mirroring findings from Western Europe more broadly. For example, 42% of British Christians would not be willing to accept a Muslim as a member of their family, but only 15% of the UK’s religiously unaffiliated say this.