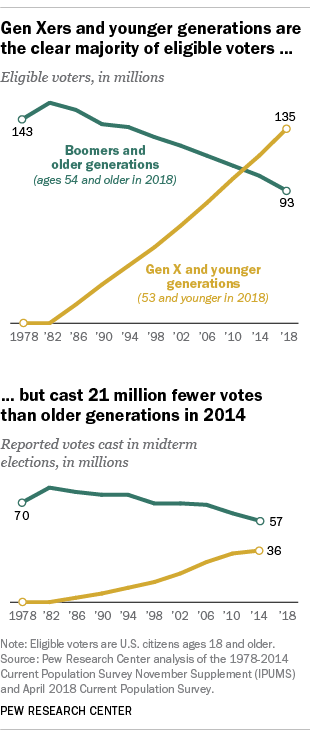

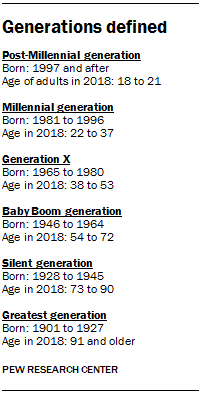

Generation X, Millennials and the post-Millennial generation make up a clear majority of voting-eligible adults in the United States, but if past midterm election turnout patterns hold true, they are unlikely to cast the majority of votes this November. Not only are younger adults less likely to participate in midterm elections, but Millennials and Gen Xers have a track record of low turnout in midterms compared with older generations when they were the same age.

As of April 2018 (the most recent data available), 59% of adults who are eligible to vote are Gen Xers, Millennials or “post-Millennials.” In the 2014 midterm election, which had a historically low turnout, these younger generations accounted for 53% of eligible voters but cast just 36 million votes – 21 million fewer than the Boomer, Silent and Greatest generations, who are ages 54 and older in 2018.

Since 2014, the number of voting-eligible Gen Xers, Millennials and post-Millennials has increased by 18 million. Some of this increase stems from Gen Xers and Millennials who have naturalized and become U.S. citizens. But the bulk of it is due to the addition of 15 million adult post-Millennials (18 to 21 years old) who are now voting age.

Meanwhile, the electoral potential of Baby Boomers and older generations has declined since the last midterm. Driven mainly by deaths, there are now 10 million fewer eligible voters among the Boomer and older generations than there were in 2014.

The generational makeup of the electorate matters because, as Pew Research Center surveys have shown, generational differences in political preferences are now as wide as they have been in decades. For example, among registered voters, 59% of Millennials affiliate with the Democratic Party or lean Democratic. About half of Boomers (48%) and 43% of the Silent Generation identify as or lean Democratic.

Whether Gen X and younger generations will be the majority of voters in the November midterms will depend on how many of those who are eligible actually turn out to vote. In the 2016 presidential election, Gen X and younger generations were a majority of voters. But turnout in midterm elections tends to be significantly lower than in presidential elections, particularly among younger adults.

In the 2014 midterm election, only 39% of Gen Xers who were eligible turned out to vote, as did a significantly smaller share of eligible Millennials (22%). It’s important to note, however, that the 2014 election is not representative of all midterms, as only 42% of all eligible voters reported voting – the lowest turnout in a midterm election since consistent data have been available.

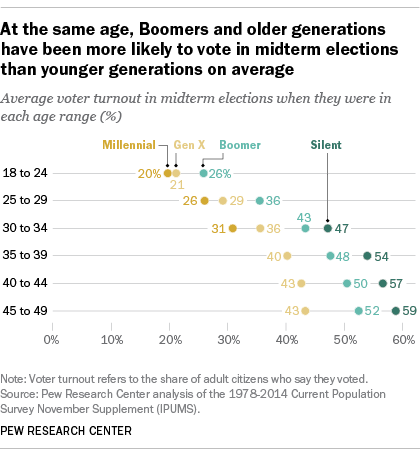

It’s difficult to predict who will turn out to vote in the upcoming 2018 midterm. A reasonable scenario might be that eligible voters would turn out as they have, on average, in past midterm elections. Gen Xers and Millennials have consistently underperformed in terms of voter turnout in midterm elections, compared with Boomers when they were the same age. Millennials have had the opportunity to vote in four midterm elections (2002, 2006, 2010 and 2014). Among Millennials who were between the ages of 18 and 24 during these elections, 20% turned out to vote, on average. By comparison, 26% of Boomers in that same age range turned out to vote in midterm elections between 1978 and 1986.

Turnout in midterm elections has been somewhat higher for older Millennials than for younger ones. Still, the gap between older Millennials and similarly aged Boomers is considerable. Among Millennials who were ages 25 to 29 at the time, 26% turned out on average for midterm elections between 2006 and 2014. That compares with 36% of eligible Boomers in that age range, on average, who voted in midterms between 1978 and 1992.

These generational comparisons over time are rough at best, however, as each midterm election has its own unique set of issues and national conditions which undoubtedly influence overall turnout.

What do these patterns tell us about potential turnout in the 2018 midterm elections?

If past turnout patterns hold – and taking into account that each generation has aged four years since 2014 – the data suggest that Gen Xers, Millennials and post-Millennials would not be a majority of voters in 2018. More specifically, extending the historical trends forward, one would expect roughly 47 million of the votes cast in 2018 would come from these three younger generations (up from 36 million in 2014), compared with 55 million votes cast by Boomer and older voters.

The analytical catch: There are, of course, no guarantees the past will repeat itself. If the younger generations were to turn out to vote at the rates Boomers did when they were younger, post-Millennials, Millennials and Gen Xers would account for the majority of votes.

Turnout depends on myriad factors, including voter engagement, and therefore these calculations are not projections of the generational turnout this November. Rather, this analysis demonstrates, based on past midterm voting behavior, how the changing generational composition of the electorate could impact voting dynamics going forward.

Methodology note: The estimated 2018 vote counts are derived by applying each generation’s average turnout rate to the electorate as of April 2018 and factoring in the assumption that the oldest of each generation will turn out as the youngest members of the next generation (for example, if Millennials ages 34 to 37 turn out to vote in the same proportion as Gen Xers ages 34 to 37 turned out to vote).