President Donald Trump has frequently criticized America’s trade deficit with China, and in recent weeks he has threatened to impose tariffs on Chinese products as a means of reducing that imbalance.

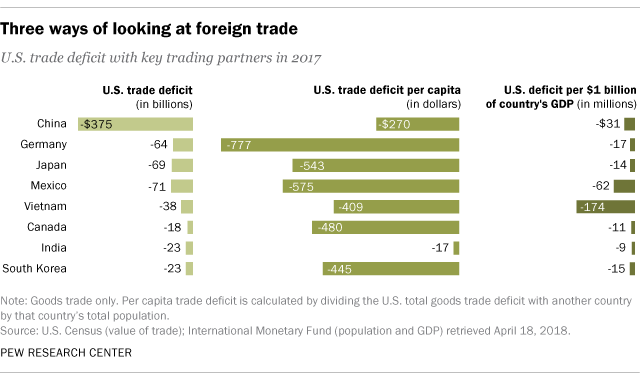

Trump’s emphasis on Beijing is hardly surprising: The United States runs a far larger merchandise trade deficit with China than with any other nation. But when the trade deficit is measured in other ways – including on a per capita basis – the U.S. actually has a larger imbalance with countries other than China.

In 2017, the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with China was $375.2 billion, up from $367.3 billion in 2015, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. (When trade in services is included, the imbalance shrinks a bit. Trump, however, has mainly directed his criticism at the deficit in autos, electronics and other such goods, reflecting his concern about the fate of the U.S. manufacturing economy.)

The merchandise trade deficit with Mexico, another country often singled out by Trump, was $71.1 billion last year – up $10.9 billion from 2015. The imbalance with Japan was $68.8 billion, relatively unchanged. And with Germany it was $64.3 billion, a decline of $10.6 billion from 2015.

But there are other ways to look at trade imbalances that take into consideration the population of America’s trading partners and the size of their economies. This perspective puts the trade numbers in a slightly different light.

On a per capita basis, for example, the U.S. deficit with Germany stands out. In 2017, Germany had a $777 per capita trade advantage with the U.S., a figure calculated by dividing the U.S. deficit with Germany by Germany’s population. Mexico had a $575 per capita advantage with its northern neighbor. But China, with its huge population, came in at only a $270 per capita advantage.

Mexico’s imbalance per capita has grown from $497 in 2015. Germany’s per capita advantage with the U.S. has actually fallen from $917 in 2015. China’s is roughly the same as in 2015, when it was $267.

A trading partner’s commercial relationship with the U.S. is also a function of the size of that nation’s economy, with smaller economies often generating huge trade advantages relative to the size of their gross domestic product (GDP).

Vietnam’s GDP was only $220 billion in 2017, according to an International Monetary Fund estimate, while its merchandise trade surplus with the U.S. was $38.3 billion. This means that every billion dollars of Vietnam’s economy generated a $174 million trade advantage with the U.S.

Mexico’s economy in 2017 was valued at $1.1 trillion. And each billion dollars of that economy created a $62 million advantage with America. China, on the other hand, with its sprawling economy, had a trade surplus with the U.S. of only $31 million per billion dollars of its GDP. And Germany’s trade advantage was just $17.4 million per billion dollars of its GDP.

Such comparison of the size of the U.S. trade imbalance with individual countries based on the size of their economies also highlights notable disparities. In 2017, South Korea’s GDP was roughly a third that of Japan’s. Yet South Korea and Japan generated roughly similar trade advantages with the U.S. per billion dollars of their GDP.