The Trump administration’s plans to impose $50 billion in tariffs on Chinese imports, as well as tariffs recently placed on imported steel and aluminum and on imports of solar panels and washing machines, mark a distinct break from decades of U.S. trade policy, which long has generally favored lower tariffs and fewer restrictions on the movement of goods and services across international borders.

The tariff actions have sparked storms of reaction in the U.S. and around the world – including threats by the European Union to place retaliatory tariffs on U.S. exports and a spate of intense lobbying to get specific countries or industries exempted before the steel and aluminum tariffs take effect March 23.

Since the turn of the 21st century, U.S. average tariff rates have consistently been at or near their lowest levels in the nation’s history; today, they’re also among the lowest in the world.

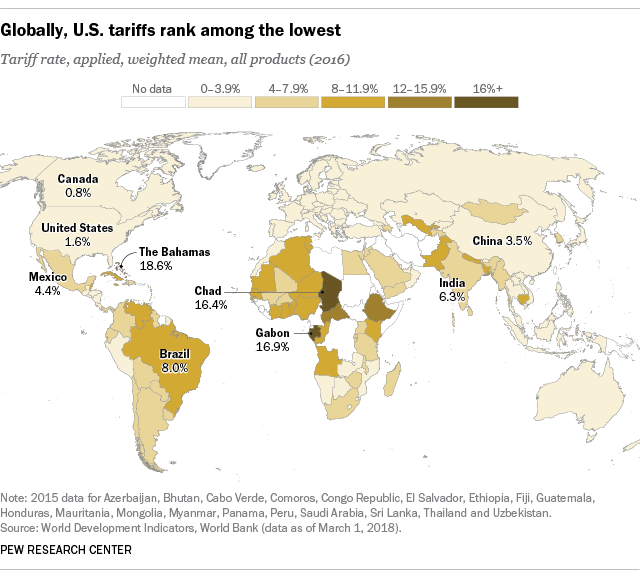

In 2016, according to the World Bank, the average applied U.S. tariff across all products was 1.61%; that was about the same as the average rate of 1.6% for the 28-nation EU, and not much higher than Japan’s 1.35%. Among other major U.S. trading partners, Canada’s average applied tariff rate was 0.85%, China’s was 3.54% and Mexico’s was 4.36%. (Those average rates are weighted by product import shares with all of each nation’s trading partners, and don’t necessarily reflect the provisions of specific trade deals. Under NAFTA, for instance, most trade between the U.S., Canada and Mexico is duty-free.)

Though the general trend globally has been toward lower tariffs, some nations still impose relatively high import taxes – particularly countries in Africa, South Asia and the Caribbean. The nation with the highest weighted-average applied tariff in 2016, according to the World Bank, is the Bahamas, at 18.6% (which was still 10 percentage points lower than the average rate in 1999). Gabon’s average applied rate was 16.9%, just above Chad’s average tariff of 16.4%.

Today’s low U.S. tariff levels are the product of a (mostly) bipartisan consensus in favor of progressively freer trade that dates back to the post-World War II era. But that consensus was emphatically not the case for the first 150 years or so of the nation’s history: Tariff policy was the subject of fierce disagreement between Republicans (and earlier, Whigs) who favored high rates to protect American industries from foreign competition, and Democrats who by and large argued that any tariffs higher than necessary to fund the federal government unfairly taxed the many to benefit the few.

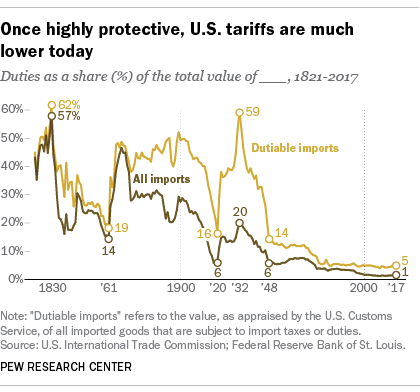

That generations-long debate can be seen in the oscillations of U.S. tariff levels throughout history. In 1821, when reliable tariff statistics begin, nearly all imports (95.5%) were taxed, and duties imposed equaled 43.2% of the total value of all imports and 45% of the dutiable value. For the next 100+ years, U.S. trade policy followed a fairly predictable pattern: When Democrats controlled the levers of power, tariff rates were lower; when Whigs or Republicans regained control, rates were higher.

The culmination of this perennial drama – what one contemporary writer called “an endless performance in which the actors are unskilled and the audience dissatisfied; and yet the same old play is staged over and over and over again” – was the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, which raised import duties on thousands of agricultural and industrial goods. By 1932, U.S. tariffs equaled 59.1% of the value of dutiable imports, the highest level since 1830. Although duties represented only 19.6% of the value of all imports (since by that time around two-thirds of imported goods were duty-free), that was still the highest level since before World War I. A 1995 survey of economic historians found broad agreement that Smoot-Hawley exacerbated the Great Depression, though to what extent is still debated.

After that experience, Congress largely gave up on setting the details of U.S. trade policy. Starting in 1934, it delegated to the president authority to negotiate trade deals with other countries and, under certain circumstances, raise or lower import duties – the authority Donald Trump has relied on for this year’s tariff increases.