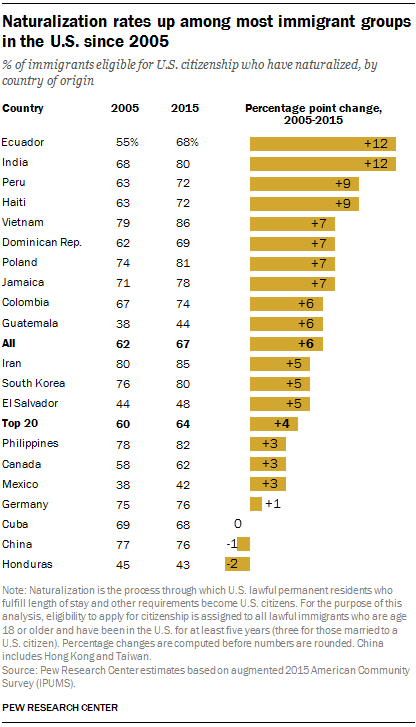

Most of the United States’ 20 largest immigrant groups experienced increases in naturalization rates between 2005 and 2015, with India and Ecuador posting the biggest increases among origin countries, according to Pew Research Center estimates of immigrants eligible for U.S. citizenship.

This trend came during a period when the total number of naturalized immigrants in the U.S. increased from 14.4 million in 2005 to 19.8 million in 2015, a 37% increase.

By 2015, eligible immigrants from India had one of the higher naturalization rates (80%) due to a 12-percentage-point increase in its naturalization rate since 2005. Only eligible immigrants from Ecuador (68% in 2015) had as large an increase. This is a bigger increase than for U.S. immigrants overall, among whom naturalization rates jumped from 62% in 2005 to 67% in 2015. (Eligible immigrants from Vietnam, 86%, and Iran, 85%, had the highest naturalization rates of any group in 2015.)

Only a few nations did not have increases. The naturalization rates among eligible immigrants from Honduras, China and Cuba declined or remained largely unchanged from 2005 to 2015 (the most recent year for which Pew Research Center estimates are available).

The naturalization rates in this analysis are cumulative, showing, in any given year, the percentage of immigrants living in the U.S. and eligible for U.S. citizenship who have ever naturalized and gained citizenship.

To be eligible for U.S. citizenship, immigrants must be age 18 or older, have resided in the U.S. for at least five years as lawful permanent residents (or three years for those married to a U.S. citizen), and be in good standing with the law, among other requirements. The multi-step process to obtain U.S. citizenship begins with submitting an application and paying a $725 fee, including an $85 biometric fee. It culminates with an oath of allegiance to the United States. Current processing times range from seven months to a year.

The U.S. government denied nearly 1 million naturalization applications from 2005 to 2015, or 11% of the 8.5 million applications filed during this time.

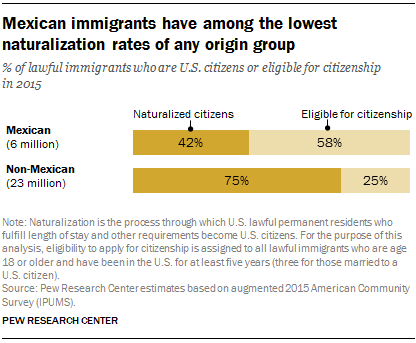

The roughly 19.8 million naturalized citizens in 2015 made up about 44% of the U.S. foreign-born population. Another roughly 11.9 million immigrants were lawful permanent residents, among whom an estimated 9.3 million were eligible to apply for U.S. citizenship. Mexican immigrants are the largest group of lawful immigrants: About 2.5 million Mexican immigrants held U.S. citizenship and another 3.5 million were eligible to naturalize.

Mexican immigrants have long had among the lowest U.S. naturalization rates (42%) of any origin group. As of 2015, the naturalization rate among eligible immigrants from Mexico was similar to those from Honduras (43%) and Guatemala (44%).

In a Pew Research Center survey of Latino adults, lawful Mexican immigrants who had not applied for U.S. citizenship cited several reasons for not having done so: A lack of English proficiency, limited interest in applying for citizenship and the financial cost of the application (some pay for a lawyer in addition to the application fee, which can raise costs).

These barriers to citizenship also affect non-Mexican immigrants. Other factors may also affect whether an immigrant applies for U.S. citizenship. Close geographic proximity of origin countries to the U.S. may lower naturalization rates, in part because immigrants from countries near the U.S. are more likely to maintain strong ties to their countries of origin, increasing the likelihood that they move back to their home country without ever obtaining U.S. citizenship.

Benefits of U.S. citizenship include being able to vote in most elections, travel with a U.S. passport, apply for some federal government jobs, receive protection from deportation and participate in a jury, among other things. In addition, research shows immigrants who become U.S. citizens have higher incomes than those who do not.

Note: Pew Research Center estimates of the lawful permanent resident population and the number of immigrants who are eligible to naturalize differ from prior estimates released by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security due to differences in methodology and data sources. For details, see the Methodology section of the Center’s report “Mexican Lawful Immigrants Among the Least Likely to Become U.S. Citizens.”