The American middle class is smaller than middle classes across Western Europe, but its income is higher, according to a recent Pew Research Center analysis of the U.S. and 11 European nations.

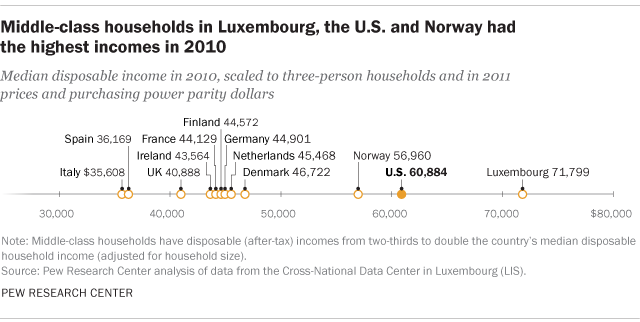

The median disposable (after-tax) income of middle-class households in the U.S. was $60,884 in 2010. With the exception of Luxembourg – a virtual city-state where the median income was $71,799 – the disposable incomes of middle-class households in the other 10 Western European countries in the study trailed well behind the American middle class.

In the Center’s analysis, the middle class in a country consists of adults living in households with disposable incomes ranging from two-thirds to double the country’s own median disposable household income (adjusted for household size). This definition allows middle-class incomes to vary across countries, because national incomes vary across countries.

The share of the adult population living in middle-class households in 2010 also varies by country. Among the countries examined, the middle-class share in Western Europe ranged from 64% in Spain to 80% in Denmark and Norway. By comparison, the U.S. lagged behind, with a middle-class share of 59% in 2010.

Western Europe’s middle classes, by U.S. income standards

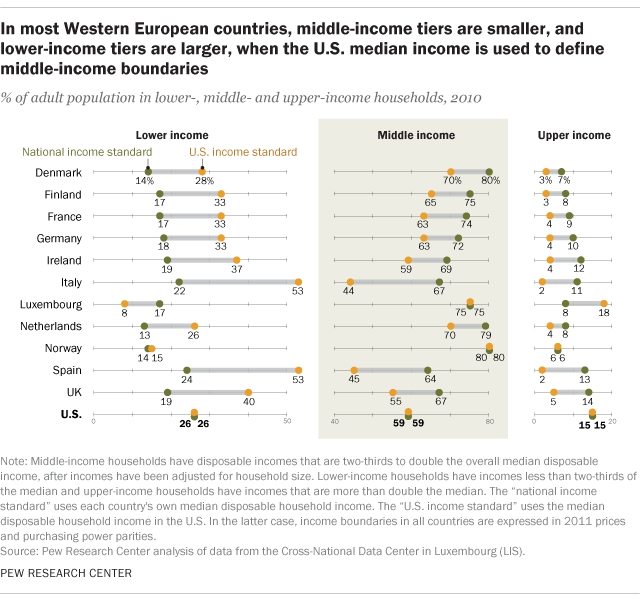

While the U.S. middle class may be smaller than those in Western Europe, its standard of living – as measured by its median income – is higher. That raises a question: What shares of adults in Western European countries have the same standard of living as the American middle class? In other words, what would the middle-class share in Western European countries be if the middle class were defined as adults living in households with the same incomes as middle-class households in the U.S.?

In 2010, middle-class households in the U.S. had incomes ranging from $35,294 to $105,881 – that is, two-thirds to double the overall median income of $52,941. This U.S. standard can be applied to any country in Western Europe after incomes are adjusted for cost-of-living differences across countries. (Incomes in this analysis are adjusted to reflect a household of three and are expressed in 2011 prices. They are also converted to purchasing power parity dollars, which adjusts for cost-of-living differences across countries. For more, see full methodology.)

When the Western European countries the Center analyzed are viewed through the lens of middle-class incomes in the U.S., the share of adults who are middle class decreases in most of them. The greatest decline is in Italy, where the middle-class share in 2010 falls from 67% under that country’s national income standard to 44% under the U.S. income standard. In other words, 44% of Italians had the same standard of living as 59% of Americans who were in the middle class in 2010.

In most Western European countries studied, applying the U.S. standard shrinks the middle-class share by about 10 percentage points – from 80% to 70% in Denmark, for example. But the middle-class shares of Luxembourg and Norway are unchanged; their overall median incomes equal or exceed that of the U.S.

Applying U.S. incomes as the middle-class standard also boosts the estimated shares of adults who are in the lower-income tier in most Western European countries (i.e., living in households with incomes less than the minimum needed to be in the American middle class). For example, in Denmark, the share of adults living in lower-income households increases from 14% to 28% under the U.S. standard. And a slight majority of adults in Italy and Spain (an estimated 53% each) are in lower-income households by U.S. standards, up from 22% and 24% respectively based on those countries’ incomes.

An expansion of the lower-income share in Western European countries when the U.S. standard is applied is typically accompanied by a decrease in the upper-income share – that is, the share of adults living in households with incomes greater than the incomes of the American middle class. In France, for example, the upper-income share falls from 9% to 4% and the lower-income share increases from 17% to 33% when the U.S. income standard is applied. Luxembourg, where incomes are higher than in the U.S., is an exception to these trends. Under the U.S. income standard, the upper-income share in Luxembourg increases from 8% to 18% and the lower-income share decreases from 17% to 8%.

Overall, regardless of how middle class fortunes are analyzed, the material standard of living in the U.S. is estimated to be better than in most Western European countries examined. But to the extent that governments in Western Europe are more likely to provide services to households that may not be captured in household income, such as the National Health Service in the UK, it is possible that differences in the quality of life between the U.S. and Western Europe are narrower.

Recent research by Charles I. Jones and Peter J. Klenow finds that economic well-being in their sample of Western European countries is similar to that of the U.S. when welfare estimates are broadened to include measures of leisure, mortality and inequality. For example, they estimate that while per capita income in France is only 67% of the level in the U.S., the broader measure of welfare for France is 92% of the level of welfare in the U.S.