The share of Americans who do not identify with a religious group is surely growing: While nationwide surveys in the 1970s and ’80s found that fewer than one-in-ten U.S. adults said they had no religious affiliation, fully 23% now describe themselves as atheists, agnostics or “nothing in particular.”

But there are differing ideas about the factors driving this trend – and its implications for society. While it appears the U.S. is becoming less religious, some contend that’s not necessarily the case. Instead, they say, the growth of the “nones” may simply indicate that people who are not religious are becoming more forthright and willing to say they have no religious affiliation, perhaps because being a “none” has become more socially acceptable.

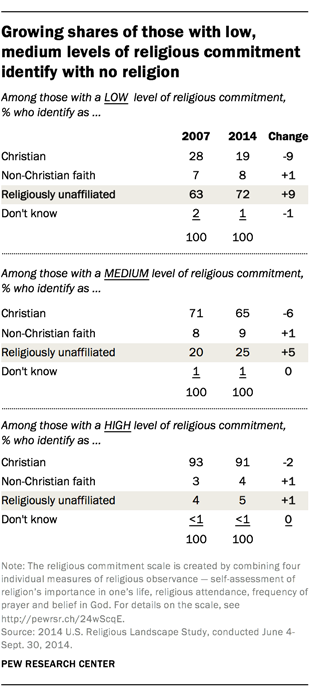

Do survey data support this notion? The answer is yes – but only partly. Two, or even three, closely related things seem to be going on. Americans who are not religiously active and who don’t hold strong religious beliefs are more likely now than similar people were in the past to say they have no religion. But that’s not the whole story, because the share of Americans with low levels of religious commitment (on a scale combining four common measures) also has been growing.

Another factor is generational change. If you think of America as a house of many different faiths, then instead of imagining the “nones” as a roomful of middle-aged people who used to call themselves Presbyterians, Catholics or something else but don’t claim those labels anymore, imagine the unaffiliated as a few rooms rapidly filling with nonreligious people of various backgrounds, including young adults who have never had any religious affiliation in their adult lives.

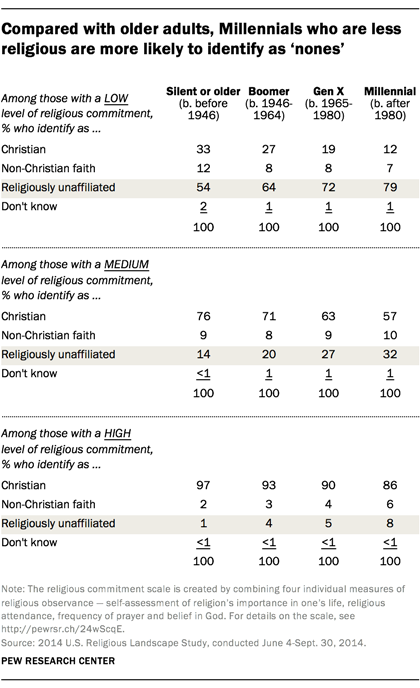

Indeed, our Religious Landscape Study finds a clear generational pattern: Young people who are not particularly religious seem to be much more comfortable identifying as “nones” than are older people who display a similar level of religious observance. Nearly eight-in-ten Millennials with low levels of religious commitment describe themselves as atheists, agnostics or “nothing in particular.” By contrast, just 54% of Americans in the Silent and Greatest generations who have low levels of religious commitment say they are unaffiliated; 45% claim a religion. A similarly striking gap between Millennials and others is also seen among those with a “medium” level of religious commitment.

Highly religious Millennials also are more likely than highly religious members of older generations to identify as religiously unaffiliated, but only modestly so.

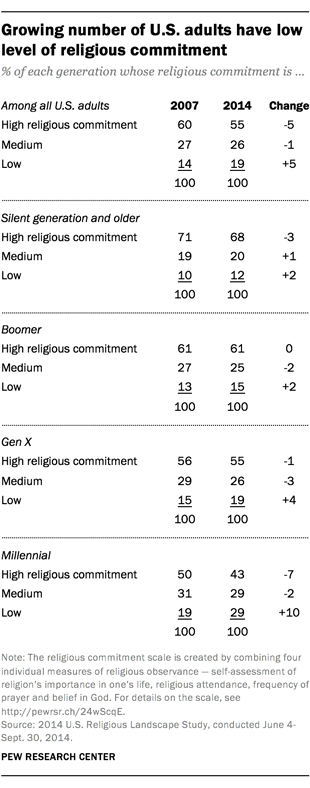

In addition, the share of the population that exhibits low levels of religiosity is growing. In 2007, for instance, 14% of U.S. adults had a low level of religious commitment on our scale, which is based on self-reported rates of attendance at worship services, daily prayer, certainty of belief in God and self-described importance of religion in people’s lives. Just seven years later, in 2014, the share of U.S. adults with low religiosity had grown to 19%.

Again, age plays a role. While the overall decline in the country’s religiosity is driven partly by modest declines among Baby Boomers and those who are part of the Silent and Greatest generations, generational replacement appears to be an even larger factor. In other words, Millennials, who make up a growing share of the population as they reach adulthood and older Americans die off, are far less religiously observant than the older cohorts. Whether Millennials will become more religious as they age remains to be seen, but there is nothing in our data to suggest that Millennials or members of Generation X have become any more religious in recent years. If anything, they have so far become less religious as they have aged.