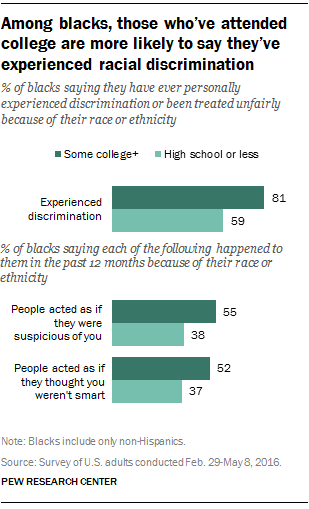

A majority of black Americans say that at some point in their lives they’ve experienced discrimination or were treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity, but blacks who have attended college are more likely than those without any college experience to say so, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

About eight-in-ten blacks with at least some college experience (81%) say they’ve faced discrimination or been treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity, compared with 59% of blacks who have never attended college.

These differences also extend to more specific incidents of racial discrimination. For example, blacks who have attended college are more likely than those who have not to say they have been met with suspicion or that someone has questioned their intelligence. Some 55% of blacks with at least some college education say that in the past 12 months someone has acted as if they were suspicious of them because of their race or ethnicity, while a similar share (52%) say people have treated them as if they weren’t smart. Among blacks with a high school diploma or less, those shares are lower, 38% and 37% respectively.

And when asked whether their race or ethnicity has made it harder, easier or hasn’t made much of a difference in getting ahead in life, about half (49%) of blacks with some college experience say their race has made it harder for them to be successful, compared with 29% of those with a high school education or less.

It may seem counterintuitive that blacks who have attended college are more likely to say they have encountered discrimination given that education is highly correlated with greater economic and social well-being. But Michael Sean Funk, a clinical assistant professor of administration, leadership and technology at New York University, said one possible explanation is that people who attend college might become more exposed – through classes or organizations – to conversations about racism and discrimination and, therefore, blacks who have attended college might have a greater awareness of these issues.

Other research suggests that college itself could be an isolating time for some black students that might give rise to perceptions of discrimination. For example, some studies have found that blacks attending majority-white institutions are more likely than those enrolled at historically black colleges or universities to report feelings of race-related stress or lower levels of faculty support. In late 2015, a slew of college protests centered on racial discrimination and lack of diversity on college campuses.

William A. Darity Jr., a professor of public policy at the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University, noted that blacks with higher levels of educational attainment are often more likely than those with less education to work in predominately white workplaces and therefore may have more opportunities to encounter racial prejudices or develop work-related stresses associated with being one of few racial minorities on the job.

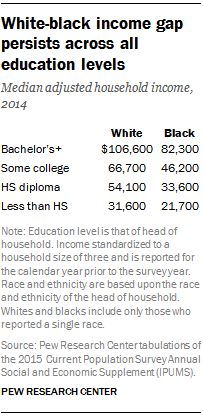

Darity also said that higher levels of education do not necessarily yield the same outcomes for blacks as for whites, and that a college education, while valuable, does not close black-white disparities in income or employment.

Indeed, a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data shows that while the income gap between black and white college-degree earners is narrower than those with less education, it still remains significant. The median adjusted household income among black householders with at least a bachelor’s degree was $82,300 in 2014, compared with $106,600 among white householders with the same level of education. Put another way, among households whose head is college-educated, black households earn 77% what white households do.

Education alone also does not close unemployment gaps between blacks and whites. The unemployment rate for blacks in 2015 was roughly double that of whites across all educational categories, according to the Center’s analysis of Census Bureau data.