President Obama’s executive action to protect millions of unauthorized immigrants from deportation is an act that both follows and departs from precedents set by his predecessors.

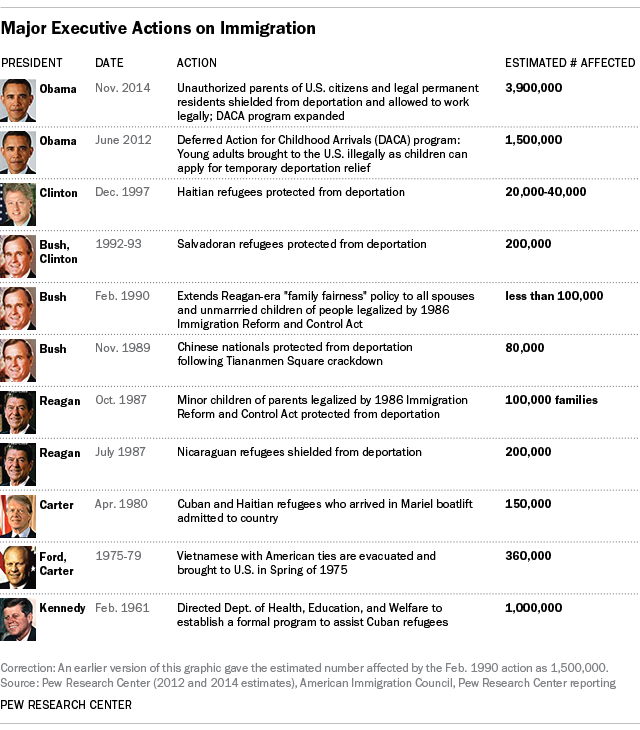

As immigrant advocates — and the White House itself — point out, presidents have a long history of using their discretionary enforcement powers to allow people to enter and remain in the country outside the regular immigration laws. But Obama’s move offers relief to more people than any other executive action in recent history — about 3.9 million people, or roughly 35% of the estimated total unauthorized-immigrant population — a point that some opponents have used to differentiate Obama’s action from those of past presidents.

Obama’s announcement follows his decision in June 2012 to grant temporary reprieves from deportation for 1.5 million eligible unauthorized immigrants who’d been brought to the U.S. as children — the program known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. In the memorandum announcing DACA, then-Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano framed it as part of the executive branch’s role “to set forth policy for the exercise of discretion within the framework of the existing law.” Obama’s action expands that program, and protects other groups, using a similar rationale.

Most previous executive actions on immigration were targeted fairly narrowly, according to a summary compiled by the American Immigration Council. The 39 “executive grants of temporary immigration relief” since 1956 listed by the council covered, among other groups, Ethiopians fleeing that country’s Marxist military dictatorship in the 1970s, Liberians who escaped their country’s brutal civil wars, and foreign students whose academic eligibility was interrupted by Hurricane Katrina.

Other actions taken by prior administrations affected considerably more people. Most of them were eventually formalized or superseded by legislation, though sometimes — as often happens with complicated subjects such as immigration — the new laws led to new issues.

Here’s a rundown:

Cubans fleeing Castro: In early 1961, at a time when thousands of Cubans were trying to escape the new Castro government, President Kennedy directed Health, Education and Welfare Secretary Abraham Ribicoff to set up a “Cuban Refugee Program” to provide federal assistance to Cuban refugees, including medical care, financial aid, help with education and resettlement, and child welfare services. That program was formalized the following year by the Migration and Refugee Assistance Act, and by subsequent legislation. By 1971, 600,000 Cuban refugees had entered the U.S.; as of 2012 there were more than 1 million Cubans living in the U.S. who had immigrated since 1959 (representing 97% of all Cuban immigrants), according to the 2012 American Community Survey.

The Cuban program, however, sparked a lawsuit from would-be immigrants from elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere, who argued that the immigrant visas given to Cuban refugees unfairly limited spots that otherwise would be available for them. In 1977, a federal court in Chicago ordered what was then the Immigration and Naturalization Service to issue so-called “Silva letters” to about 250,000 people — nearly all Mexicans living in the Southwest, according to a 1985 Los Angeles Times article — giving them temporary protection from deportation and letting them work while the complex case worked its way through the courts. Eventually, about 145,000 Silva letter holders received visas; the rest (at least those who were still living in the U.S.) remained in administrative limbo until the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act enabled them to apply for legal permanent residency.

Refugees from the Indochina wars: In early 1975, when it became clear South Vietnam was going to fall to the communist North, the Ford administration evacuated around 130,000 Vietnamese from Saigon. Ford and his successor, Jimmy Carter, subsequently allowed more Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian refugees to come to the U.S.; between 1975 and 1979, about 360,000 people from the countries of Indochina were allowed to remain in the country.

Mariel boatlift: Between April and October 1980, approximately 125,000 Cubans and 25,000 Haitians (who were trying to escape that nation’s grinding poverty and the brutal Duvalier dictatorship) arrived in south Florida by boat. The Carter administration used its discretionary authority to admit most of them into the country; those migrants eventually were made legal permanent residents by the 1986 immigration-reform law.

Spouses and children: The 1986 law, however, created a new dilemma: how to deal with spouses and children of newly-legalized immigrants who didn’t themselves qualify for legal status. In October 1987, the Reagan administration said it wouldn’t seek to deport minor children living with their parents as long as both parents qualified for amnesty under the 1986 law. Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, expanded that policy in February 1990: Under the new “family fairness” rules, all spouses and unmarried children of people who gained legal status under the 1986 law could apply for permission to remain in the country and receive work permits. Bush’s policy was formalized later that year as part of the Immigration Act of 1990.

Central American refugees: The conflicts in El Salvador, Nicaragua and elsewhere in Central America in the 1980s and early 1990s led to a new series of executive actions on immigration. In July 1987, Attorney General Edwin Meese announced that the approximately 200,000 Nicaraguan exiles then living in the U.S. would not be deported so long as they had a “well-founded fear of persecution.” Meese also encouraged them to seek work permits and reapply for asylum if they’d been denied before.

A similar number of Salvadoran refugees were allowed to remain in the country in “temporary protected status” under the provisions of the 1990 immigration law. When that status expired two years later, Bush extended it; his successor, Bill Clinton, extended it again, until the end of 1994. Eventually, the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act of 1997 allowed Nicaraguans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans and others to apply to become legal permanent residents. This opportunity was eventually extended to several thousand Haitian migrants (estimates range from 20,000 to 40,000) who’d been left out of the 1997 law — first by executive action from President Clinton, and ultimately through passage of the Haitian Refugee Immigrant Fairness Act enacted in October 1998.

Chinese in U.S.: On at least one occasion, a president actively discouraged Congress from carving out an exception to the immigration laws. In November 1989, the first President Bush vetoed a bill that would have provided emergency immigration relief for Chinese nationals in the United States following the Tiananmen Square massacre. In his veto message, Bush said that he was already providing greater protections to the Chinese through administrative actions and “opposed congressional micromanagement of foreign policy.” In April 1990, Bush formalized and extended his policy by Executive Order 12711.

Correction: This posting has been updated with a revised total of 3.9 million unauthorized immigrants affected by the president’s order.