Andrew Kohut, the founding director of Pew Research Center and its president from 2004 to 2012, was one of the nation’s leading pollsters. He died in 2015. His work, over three decades, won him wide respect for his expertise and ability to craft stories about what people could learn from survey research. One of his particular talents was to reach back in time to take a snapshot of the mood of Americans in another era to show how much times had changed.

Here is one of those articles, originally published on Aug. 8, 2014.

Forty years ago today, Richard Nixon announced his resignation from the nation’s highest office, making that decision in the face of almost certain impeachment by the House and plummeting public support, as a majority of Americans called for his removal from office. But it happened in stages.

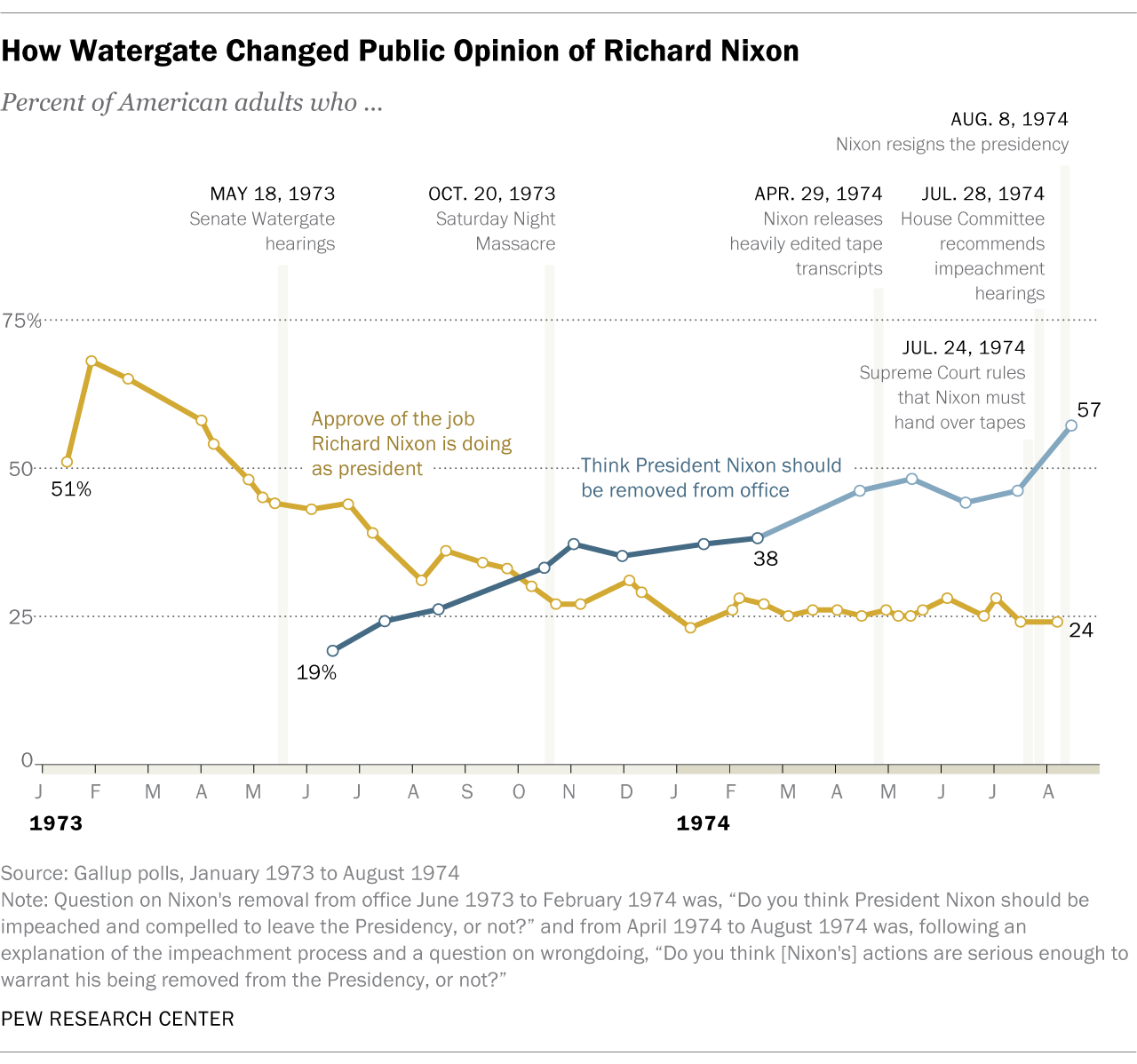

Nixon had won reelection in 1972 by a landslide and began his second term with a lofty 68% Gallup Poll approval rating in January 1973. But the Watergate scandal – which started with an effort to bug the Democratic National Committee office at the Watergate Hotel and subsequent efforts to cover it up – quickly took a heavy toll on those ratings, especially when coupled with a ramp-up in public concerns about inflation. By April, a resounding 83% of the American public had heard or read about Watergate, as the president accepted the resignations of his top aides John Ehrlichman and H.R. Haldeman. And in turn, Nixon’s approval ratings fell to 48%.

But that was just the beginning of the toll the scandal would take on the president that year. The televised Watergate hearings that began in May 1973, chaired by Sen. Samuel Ervin, commanded a large national audience – 71% told Gallup they watched the hearings live. And as many as 21% reported watching 10 hours or more of the Ervin proceedings. Not too surprisingly, Nixon’s popularity took a severe hit. His ratings fell as low as 31%, in Gallup’s early August survey.

The public had changed its view of the scandal. A 53% majority came to the view that Watergate was a serious matter, not just politics, up from 31% who believed that before the hearings. Indeed, an overwhelming percentage of the public (71%) had come to see Nixon as culpable in the wrongdoing, at least to some extent. About four-in-ten (37%) thought he found out about the bugging and tried to cover it up; 29% went further in saying that he knew about the bugging beforehand, but did not plan it; and 8% went all the way, saying he planned it from beginning to end. Only 15% of Americans thought that the president had no prior knowledge and spoke up as soon as he learned of it.

Yet, despite the increasingly negative views of Nixon at that time, most Americans continued to reject the notion that Nixon should leave office, according to Gallup. Just 26% thought he should be impeached and forced to resign, while 61% did not.

A lot of key scandal events were to follow that year and into 1974, but public opinion about Watergate was slow to change further, despite the high drama of what was taking place. For example, October 1973 was a crucial month as the courts ruled that the president had to turn over his taped conversations to special prosecutor Archibald Cox, and subsequently Nixon ordered for the dismissal of Cox in what came to be known as the Saturday Night Massacre. The public reacted, but in a measured way. In November, Gallup showed the percentage of Americans thinking that the president should leave office jumping from 19% in June to 38%, but still, 51% did not support impeachment and an end to Nixon’s presidency.

In the spring of 1974, despite the indictment of top former White House aides, and Nixon’s release of what were seen as “heavily edited” transcripts of tapes of his aides plotting to get White House enemies, the public was still divided over what to do about the president. For example, by June, 44% in the Gallup Poll thought he should be removed from office, while 41% disagreed.

Only in early August, following the House Judiciary Committee’s recommendation in July that Nixon be impeached and the Supreme Court’s decision that he surrender his audio tapes, did a clear majority – 57% – come to the view that the president should be removed from office.

But once he was gone, the Americans were not quick to forgive and forget. In September, a 58% majority said Nixon should be tried for possible criminal charges. And they took the view that he should not be let off the hook easily, if found guilty. By a margin of 53% to 38%, the public thought that President Ford should not pardon Nixon, if he was found guilty.

The latter sentiment of course, would carry on, and be crucial to the outcome of the next presidential election. Ford did pardon Nixon in September, an act that was followed by a plummet of his own poll numbers, and later was seen as a factor in his loss to Democrat Jimmy Carter in the 1976 presidential election.