Tuesday’s Supreme Court decision upholding Michigan’s ban on affirmative action affects more than college admissions, and more than just Michigan. Seven other states have similarly broad bans in their constitutions or statute books, and opponents of affirmative action have called on other states, and the federal government, to follow suit.

In a 6-2 decision marked by divisions among the justices (three concurrences in addition to Justice Kennedy’s plurality opinion, which only two other justices joined), the Court was careful to stress that it wasn’t ruling on “the constitutionality, or the merits, of race-conscious admissions policies in higher education.” Rather, the key question was “whether, and in what manner, voters in the States may choose to prohibit the consideration of racial preferences in governmental decisions…”

Affirmative action, in the sense of active measures to improve work or educational opportunities for members of historically disadvantaged groups, is an outgrowth of the civil-rights movement of the 1960s. In 1965, President Johnson issued Executive Order 11246, which (as amended) requires federal contractors to “take affirmative action to ensure that equal opportunity is provided in all aspects of their employment.” Over the following years, affirmative-action programs became common at the state and local levels as well, including at colleges and universities.

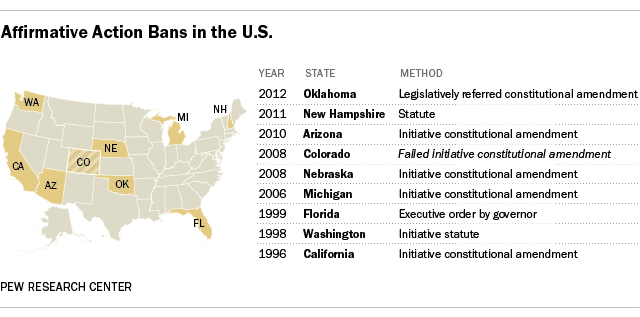

In 1996, following years of controversy over affirmative action that dates back to the 1978 Bakke decision), California became the first state to enact a formal ban on racial and other preferences, when voters approved Proposition 209. Since then, Michigan and six other states — Washington, Florida, Nebraska, Arizona, New Hampshire and Oklahoma — have adopted similar bans. Most of those measures include language similar or identical to Prop 209’s key provision: that the state (including but not limited to public colleges and universities) “shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.”

Six of the bans were adopted by voters (five via initiative petitions, one by legislative referral). The only state where an anti-affirmative action initiative failed at the ballot was Colorado, where voters narrowly rejected Amendment 46 in 2008.

Nationally, however, Americans appear strongly supportive of affirmative action, at least in the realm of higher education. In a Pew Research Center survey conducted last month, 63% of people said such programs aimed at increasing the number of black and minority students on college campuses were a good thing, versus just 30% who called them a bad thing.