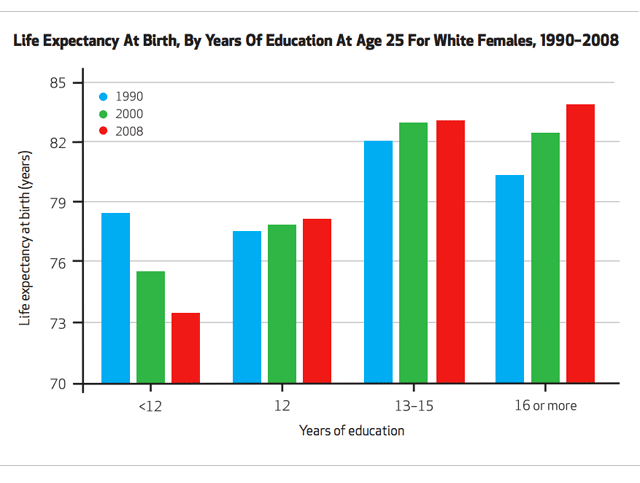

For nearly three decades researchers have known that better-educated adults are living increasingly longer than those with less education. (Kids: One more reason to stay in school.)

Then in the mid-1980s a new trend emerged: The education-mortality gap began growing much faster among women than among men. By 2006, white women without a high school degree were actually dying at a younger age than they had been a decade earlier. Meanwhile, the life expectancy of better-educated women and men continued to rise, report Jennifer Karas Montez and Anna Zajacova in the latest issue of the Journal of Health and Social Behavior.

These researchers found that during the 1997 to 2001 period, a middle-aged or older white woman without a high school degree had a 37% greater chance of dying than a comparably aged white woman with at least a high school degree. This differential grew to 66% during the 2002-2006 period. Their results mirror those of other researchers who have studied changes in mortality over different time periods (see chart above).

Expressed slightly differently, Montez and Zajacova found that life expectancy for better-educated white women increased by one year in 1997-2001 but fell by a year among those with less than a high school degree — a group that comprised about 13% of all white women.

Their results are based on data collected from 1997 through 2006 on white women aged 45 to 84 for the National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File project. The sample of 46,744 women includes 4,053 who died during the study period.

These data detectives also attempted to identify why less educated white women are living shorter lives. Their work points to the increasingly powerful role that two factors—economic circumstances and health behaviors—appear to play in longevity. Montez is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholar at Harvard and Zajacova teaches at the University of Wyoming.

“Accounting for economic circumstances (employment, occupation, poverty, home ownership and health insurance) and health behaviors (smoking, obesity, and alcohol consumption) together explained the growing education gap in mortality,” they found.

On nearly all of these specific measures of disadvantage, the gap between high- and low-educated white women grew over the study period. For example, the percentage of women without a high school diploma who had private health insurance fell from 61% in 1997 to 56% in 2006, but declined by only a percentage point to 84% among better-educated white women. As a consequence, the health insurance gap increased from 24 to about 27 percentage points.

Similarly, the percentage of low-educated women “who had never smoked decreased from 52% to 50% between the two periods, whereas the percent among high-educated women increased from 54%t to 55%, which widened the education gap from 2% to 5%.” They also found growing disparities in employment status, obesity, and drinking habits.

The link between longevity, smoking and other bad health habits is well established. But the role of unemployment that Montez and Zajacova highlighted is new.

How does having a job make you live longer? They suggest that employment may provide “both manifest (e.g., income) and latent benefits, such as social networks and supports and a sense of purpose; it enhances self-esteem; and it offers mental and physical activity.”