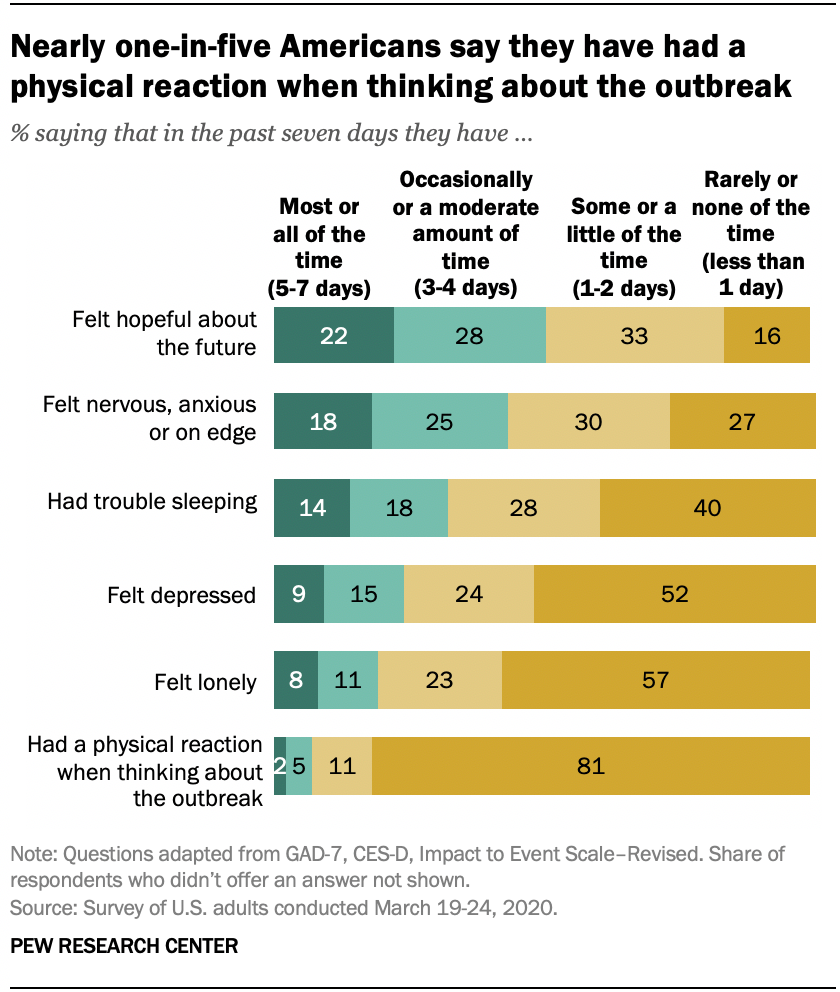

Health experts are concerned about the potential mental health effects of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States, and mental health hotlines report a substantial uptick in calls since the outbreak began. Nearly one-in-five U.S. adults (18%) say they have had a physical reaction at least some or a little of the time when thinking about the outbreak, according to a new Pew Research Center survey conducted March 19-24. This is particularly true of those affected financially.

When asked more broadly how they’ve felt in the past seven days, not in the context of the coronavirus outbreak, 18% report experiencing nervousness or anxiety most or all of the time during the past week. For context, a 2018 federal survey – which was not taken in the midst of a national crisis – found 9% of U.S. adults reported feeling nervous most or all of time over the past 30 days, indicating that the current level might be above normal.

How we did this

To measure the psychological distress people in the U.S. may be experiencing during the COVID-19 outbreak, 11,537 U.S. adults were surveyed March 19-24, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other characteristics.

The index used in this analysis measures the total amount of mental distress that individuals reported experiencing in the past seven days, which for this survey was roughly the week after President Donald Trump’s Oval Office address about COVID-19 the evening of March 11. The low distress category includes half of the sample; very few in that group said they were experiencing any of the types of distress most or all of the time. The middle category includes roughly one-quarter of the sample, as does the high distress category. A large majority of those in the high distress group reported experiencing at least one type of distress most or all of the time in the past seven days.

The questions used to measure the levels of psychological distress were developed with the help of the COVID-19 and mental health measurement group from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH): M. Daniele Fallin (JHSPH), Calliope Holingue (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH), Renee Johnson (JHSPH), Luke Kalb (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH), Frauke Kreuter (University of Maryland, University of Mannheim), Elizabeth Stuart (JHSPH), Johannes Thrul (JHSPH) and Cindy Veldhuis (Columbia University).

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology. Here is more information about the American Trends Panel.

To help track and assess these effects of the COVID-19 outbreak, Pew Research Center asked members of its American Trends Panel how often in the past seven days they had experienced five different types of psychological distress. These included general questions (not tied to the outbreak) about anxiety, sleeplessness, depression and loneliness. One question asked about physical reactions when thinking about the outbreak, such as sweating, trouble breathing, nausea or a pounding heart. Another question asked people if they had felt hopeful about the future. Respondents were then placed into three categories of psychological distress (high, medium and low) based on their responses to five of the items, excluding hopefulness.

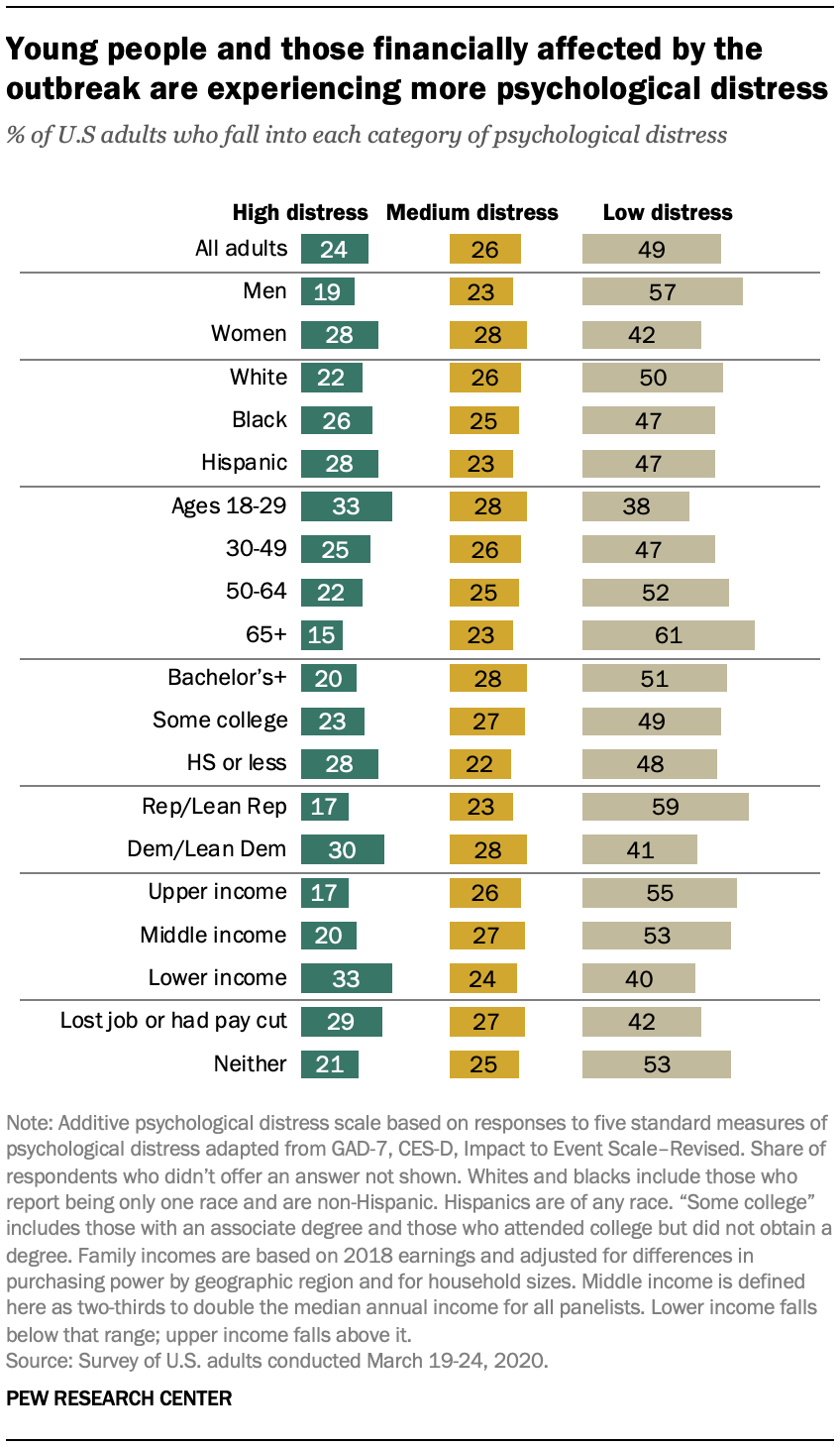

Psychological distress varies considerably across different demographic groups in the survey, in patterns familiar to public health experts. It is also correlated with experiences and perceptions of the coronavirus outbreak. It is important to note that – other than the question asking specifically about reactions to thinking about the outbreak – there is no way to be certain whether variations in distress are attributable to the COVID-19 outbreak or if they primarily reflect underlying, preexisting differences. The answer may be both. After more time passes, future surveys of these same individuals will be better able to provide an answer. At a minimum, the patterns identify groups that may be more vulnerable to the psychological effects of the crisis.

Women, young people, those with lower incomes and those whose jobs or income have been cut by the outbreak are more likely than other groups to fall into the high distress category. One-third of adults ages 18 to 29 are in the high distress group, compared with just 15% of adults 65 and older. Women of all ages are more likely than men to be in the high distress group (28% vs. 19% for men), but women ages 18 to 29 (37%) are particularly likely to be classified as experiencing higher levels of distress.

One-third of lower-income Americans (33%) are in the high distress group, as are 29% of those in households that have experienced job or income loss as a consequence of the outbreak. By contrast, just 17% of those in upper-income households are categorized as experiencing high levels of distress, and only 21% of those whose employment situations have thus far been unaffected are in the high group.

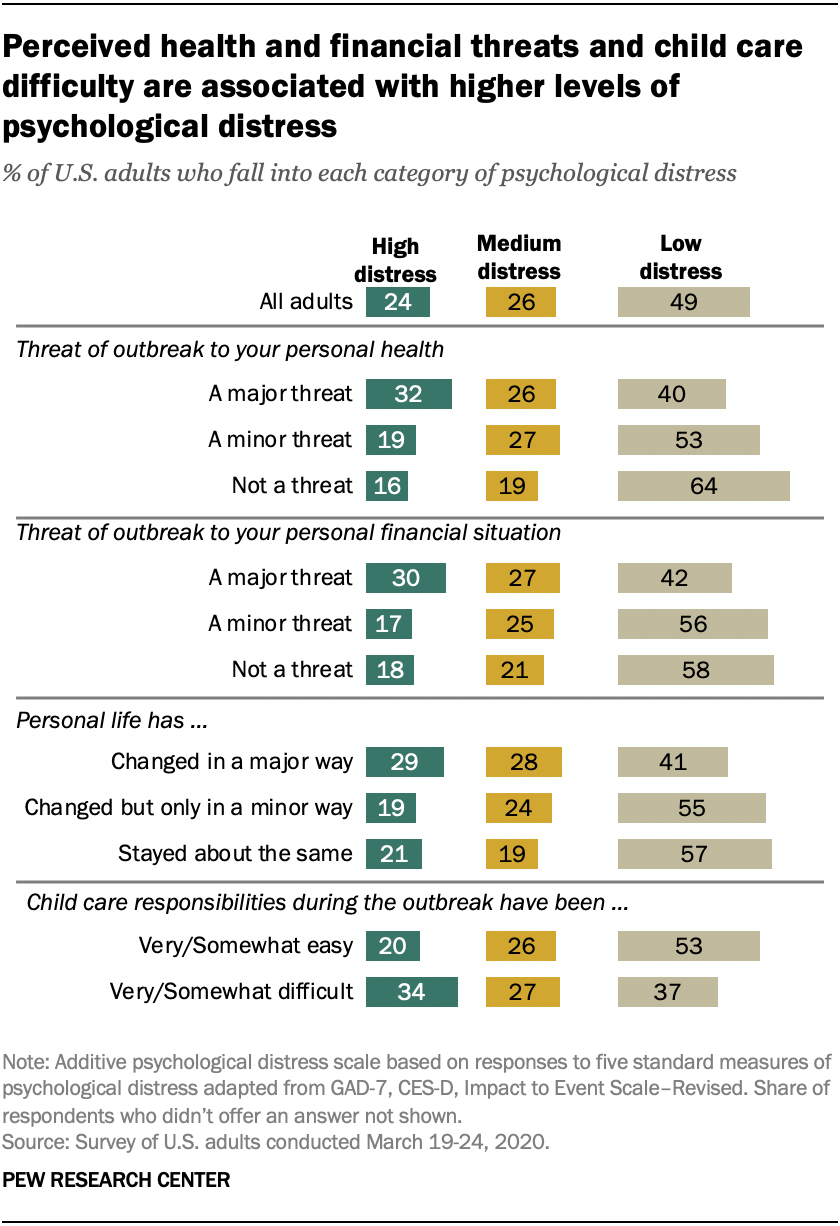

Perceptions of personal threat from the outbreak – whether physical or financial – are also associated with higher levels of psychological distress. Among those who see the outbreak as a major threat to their personal health, about one-third (32%) fall into the high distress category; among those who say it is not a threat to their health, just 16% do. And 30% who see the outbreak as a major threat to their personal financial situation fall into the high distress category, compared with 18% among those who say it is not a threat.

People who report difficulty dealing with child care responsibilities during this time of school closings and work-from-home obligations – about one-third of those with young children – may be experiencing higher levels of psychological distress. Among those who have children under 12 living in the home and who say that child care responsibilities during the outbreak have been “somewhat” or “very difficult,” 34% fall into the high distress group, a number that rises to 42% among women.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.