Muslim societies have sometimes faced criticism for failing to adequately educate women. Boko Haram’s kidnapping of schoolgirls in Nigeria and the Taliban’s attack on Pakistani education activist Malala Yousafzai have contributed to this perception, raising the question of whether Islam itself hampers women’s education. But a new analysis of Pew Research Center data on educational attainment and religion suggests that economics, not religion, is the key factor limiting the education of Muslim women.

It’s true that, historically, Muslim women have received less schooling than females of other major religions (except Hindus); they also have lagged behind Muslim men in educational attainment, according to previous analysis by Pew Research Center. More recently, however, Muslim women have been catching up – not only with Muslim men but also with other women around the world.

As Muslim women move up the educational ladder, the role of religion as a predictor of academic attainment is diminishing, according to the new study, which analyzes the Center’s education data and appears in the journal Population and Development Review. The findings challenge claims that there’s a culture clash between Muslim and Western societies over gender equality in education. (The study was authored by David McClendon, Conrad Hackett, Michaela Potančoková, Marcin Stonawski and Vegard Skirbekk. Hackett is a senior demographer and associate director of research at Pew Research Center. McClendon is a former research associate at the Center.)

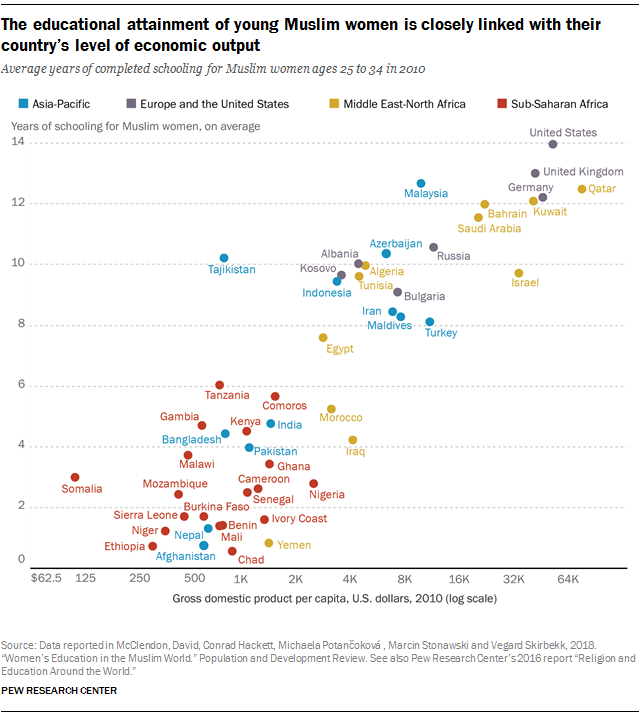

The analysis shows that a country’s wealth – not its laws or culture – is the most important factor in determining a woman’s educational fate, with women in oil-rich Gulf countries, especially, making some of the biggest educational leaps in recent decades.

For example, young Muslim women (born between 1976 and 1985) in Saudi Arabia, which calls itself an Islamic state and enforces conservative gender laws, have an average of 11.5 years of schooling, compared with 11.8 years for the country’s young men and just two years of education for older Muslim women (those born between 1935 and 1955). These numbers indicate that Saudi Arabia has increased access to schooling for women and has come closer to closing the education gender gap. (The study measured only the education of Saudi citizens and not trends among the large population of noncitizen migrant workers in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries.) By comparison, the average duration of schooling for young U.S. men and women – across religious groups – is around 13 years.

By contrast, in Mali – also a predominantly Muslim country, but one that is economically poor – young Muslim women have an average of only 1.4 years of schooling, compared with 2.7 years for the country’s young men. And older Muslim women in Mali (those born between 1935 and 1955) average half a year of schooling. These figures show that Mali has seen only modest gains in the education of Muslim women. The same pattern has unfolded in sub-Saharan Africa overall, where young Muslim women average 2.5 years of school, up from 0.8 years of school among the older generation.

To test the extent to which Islam itself influences a woman’s educational attainment, the researchers examined factors in Muslim communities that might play a role, such as the degree of gender discrimination in a country’s family laws, the percentage of its population that is Muslim and the share of Muslims who reported religion is very important to them. The study finds that none of these elements had a significant impact on the results.