Everyone knows that our genes predispose us to be tall or short, blue-eyed blonds or brown-eyed brunettes, smart or not-so-smart. Now new research finds that, to a surprisingly large degree, our genes also shape our political beliefs and orientation.

Using data collected from a large sample of fraternal and identical twins, a research team found that genes likely explain as much as half of why people are liberal or conservative, see the world as a dangerous place, hold egalitarian values or embrace hard-core authoritarian views.

Individual experiences and other social influences explain much of the remaining variation in political attitudes, reports psychologist Cary Funk, who headed the eight-member team. Their results were just published in the latest issue of Political Psychology. (For the record, Funk is a senior researcher at the Pew Research Center and carried out this study while an associate professor at Virginia Commonwealth University.)

These researchers based their conclusions on a survey of twins in the Minnesota Twin Registry (MTR). Based at the University of Minnesota, the registry includes approximately 8,000 twin pairs born in Minnesota from 1936 t0 1955. The study includes both identical (or monozygotic twins)—those that developed from the same egg and share identical genetic material—and fraternal (or dizygotic twins) who only have, on average, about half of their genes in common. The twins were recruited into the registry from about 1983 to 1990 when most were middle-aged.

Twin studies are particularly useful in answering tricky nature vs. nurture questions. Do people think as they do because of their genetic makeup—the “nature” half of the puzzle—or do they embrace certain beliefs because of how they were nurtured by their parents as well as through personal experiences?

Since nearly all twins are raised in the same home environment with the same parents, twin studies are seen as a natural experiment that can establish whether or not there is a substantial genetic component underlying political ideology or other beliefs. That’s because researchers usually assume that both twins were generally disciplined the same way, received the same religious, moral and social instruction, and presumably heard the same political rants by dad and mom around the dinner table.

To disentangle the effects of nature and nurture, researchers conduct a series of comparisons. They first determine how closely correlated the attitudes of identical twins are on a particular measure, say whether they identify themselves as strong conservatives, strong liberals or somewhere in-between. Then they do the same with fraternal twin pairs. Finally, they compare the two correlations.

If identical twins are significantly more alike in their views than fraternal twins, that’s strong evidence pointing to a genetic basis for the attitude. Moreover, these comparisons can also pinpoint which attitudes are due to their shared environment (a term which includes parental and other family influences that make family members similar to each other) and also which ones are shaped by unique individual factors—basically everything else that can shape political views.

The twins used in Funk and her colleagues’ study were all born from 1947 to 1956 (a subset of the larger twins sample). They were asked batteries of questions that measured personality traits, social and political values and political ideology. A total of 1,192 respondents who were part of a matched twin pair were surveyed by researchers in 2008 and 2009.

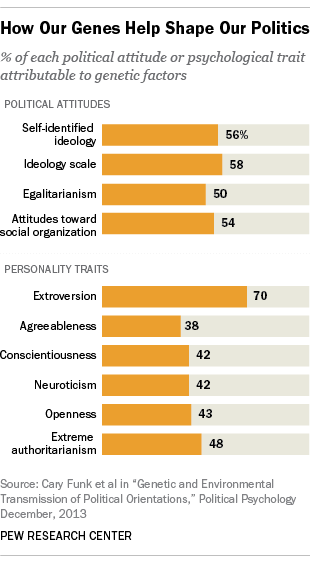

They found that somewhat more than half of the difference in self-identified political ideology (56%) is explained by genetic factors. The remainder was explained by unique factors affecting one twin and not the other. A second measure of ideology based on 27 questions produced a similar result (genes appeared to explain 58% of the difference between individuals).

Funk and her colleagues also found that about half (48%) of the difference in authoritarian beliefs is inherited. To measure authoritarianism, they asked respondents to record their reactions to 15 statements on a seven-point scale that ranged from “Very negative” (coded as 1) to “Very positive” (7). Some examples: “Our country needs a powerful leader, in order to destroy the radical and immoral currents prevailing in society today,” and “Our country needs free thinkers, who will have the courage to stand up against traditional ways, even if this upsets many people.”

They tested the heritability of egalitarianism. Twins were asked how much they agreed or disagreed with five statements, including “If wealth were more equal in this country we would have many fewer problems,” and “We have gone too far in pushing equality in this country.” Again they found that half of the variance appeared to be explained by genetic factors.

Similarly, genes seemed to be linked to 54% of the variance in four questions that measure attitudes about social organization and structure, called the “Society Works Best” scale. Two examples: “Society works best when…leaders are obeyed OR leaders are questioned” and “Society works best when…people realize the world is dangerous OR people assume that all those in faraway places are kindly.”

They also asked questions that measure core psychological traits—psychology’s so-called “Big Five”—and found that at least some of the explanation why people are the way they are again seems to lie in the genes. For example, fully 70% of the reason why people are extroverts is gene-linked, as is 43% of “openness,” 42% of neuroticism and conscientiousness, and 38% of agreeableness.

Two cautions: The authors note the MTR sample of twins is not representative of the country as a whole—“it is middle-aged, overwhelmingly white, and geographically concentrated in the Midwest,” they write. And when it comes to political attitudes, genes are not destiny. Upbringing and unique factors and experiences interact with genes or combinations of genes to shape whether someone is a political liberal or conservative, votes in every election or isn’t registered to vote, or supports Obamacare or the Tea Party.