As if married people don’t have enough to worry about, a new study suggests that the divorce of a friend or close relative dramatically increases the chances that you too will divorce.

A research team headed by Rose McDermott of Brown University analyzed three decades of data on marriage, divorce and remarriage collected from thousands of residents of Framingham, Massachusetts.

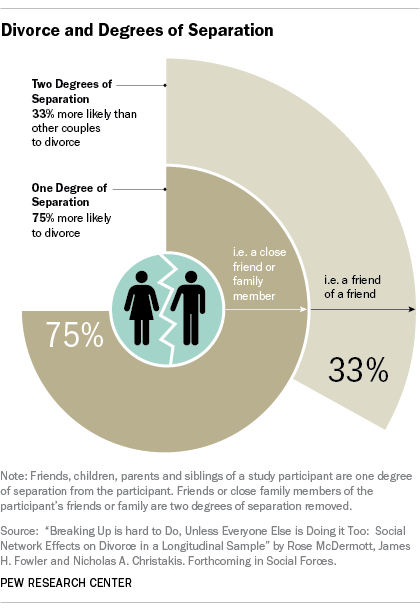

McDermott and her colleagues found that study participants were 75% more likely to become divorced if a friend is divorced and 33% more likely to end their marriage if a friend of a friend is divorced.

So divorce is contagious…and you can catch the divorce bug from your friends—even from a friend of a friend?

“Approaching the epidemiology of divorce from the perspective of an epidemic may be apt in more ways than one,” McDermott and her colleagues wrote in a forthcoming article in the journal Social Forces. “The contagion of divorce can spread through a social network like a rumor, affecting friends up to two degrees removed.”

Sociologists call the phenomenon “social contagion”—the spread of information, attitudes and behaviors through friends, families and other social networks.

Examples of social contagion run the gamut from adolescent sexual behavior to the spread of phantom diseases in a workplace. Economist Ilyana Kuziemko reported in a 2006 paper titled “Is Having Babies Contagious?” that brothers and sisters are significantly more likely to have a child soon after a sibling gives birth. A research team in Arkansas tracked how obesity appeared to spread in elementary school classrooms.

McDermott and her colleagues base their findings on the data collected in the Framingham Heart Study, one of the country’s longest-running and most influential longitudinal surveys (longitudinal surveys follow the same groups of people over time). The project began in 1948 to study the risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Researchers interviewed 5,209 men and women between the ages of 30 and 62 in Framingham, located 20 miles west of Boston and today home to 67,000 people.

About every two years the subjects are re-interviewed and undergo a detailed medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests. In 1971, a second generation was added to the original study group when researchers enrolled 5,124 of the original participants’ adult children and their spouses. This “offspring” cohort is re-examined about every four years.

Degrees of Separation

For those unfamiliar with the concept “degrees of separation,” here’s a short primer: individuals with direct social ties to you-your friends, children, parents and siblings are one degree of separation removed to you. The friends of your friends are two degrees of separation connected to you, the friends of the friends of your friends are three degrees removed, and so on.

The phrase entered pop culture in the early 1990s with the John Guare play and subsequent movie “Six Degrees of Separation,” a reference to the claim that everyone in the world is, on average, only six degrees removed from anyone else. The idea morphed into the game “Six degrees of Kevin Bacon” in which movie buffs try to link actors to movies in which Bacon appeared.

Academics specializing in social networks have been drawn to the study because, among other things, it asks people to name their friends and family members. Since Framingham is so small and the study sample so large, lots of study participants are friends or are related to someone else in the study. In fact, each study participant on average named nearly 11 other study participants as a friend or family member, a data gold mine for researchers studying how friends and family ties affect health and behavior.

For their study, McDermott and her colleagues used data collected in seven successive rounds of interviews beginning in 1971 and ending in 2001. (Of course many of the first generation had already died or would die sometime during the 30-year study period while a small number of others had dropped out of the study along the way. Among the adult children cohort, about eight-in-ten participated in the seventh round of examinations and interviews.)

The researchers caution that their study group is not representative of the country as a whole. That means their results cannot be said to reflect what would have been found if a nationally-representative sample of all adults had been surveyed. For example, study participants are nearly all white, better educated and more likely to be middle class and were less likely to be divorced than the U.S. population. (They note these demographic characteristics are also associated with lower divorce rates nationally.) Nor does the study account for ties to people who were not part of the Framingham study.

Overall, they found that the divorce of a friend or close relative significantly increased the probability of divorce. For example, about 9% of the adult children of the 1948 study group were divorced at least once. The findings suggest that the chances of divorcing increase to approximately 16% if a friend or close family member has been divorced — an increase of 75% over the overall divorce rate. The probability of divorce rises to roughly 12% if friends and relatives of the participant’s friends and relatives divorces. But the effect then vanishes, and the divorce of someone three degrees removed—a friend of a friend of a friend—does not significantly change the likelihood that a couple will separate.

“We suggest that attending to the health of one’s friends’ marriages might serve to support and enhance the durability of one’s own relationship,” they conclude. “Although the evidence we present here is limited to a single network…marriages endure within the context of communities of healthy relationships and within the context of social networks that encourage and support such unions.”

Other insights from the study:

- People in the study group who have been divorced are more likely to marry someone else who has been divorced, particularly those who re-couple relatively soon after they end their previous marriage. Compared to others, those who remarried since the last study period were four times more likely to marry a divorcee.

- Divorced participant became less popular, in part because they may lose as friends members of their former spouse’s friends network. “In addition, newly single people may be perceived as social threats by married friends who worry about marital poaching.”

- More popular people—participants with more friends in their social network—were less likely to divorce than those with fewer friendships. Part of the reason may be that “a strong, supportive friendship network” protects a couple’s marriage by “mak[ing] it easier for individuals to weather inevitable marital stresses.”

About the authors: Rose McDermott is a professor of political science at Brown University. Her research specialties include experimental methods and political psychology. James H. Fowler, a specialist in social networks, is professor of medical genetics and political science at the University of California, San Diego. Nicolas A. Christakis is a physician and sociologist at Yale University and co-director of the Yale Institute for Network Science.