With less than a week to go before a possible government shutdown, long-time political observers are tapping their memories for lessons from the last time the government shut down, in the fall of 1995 and winter of 1996.

One lesson that people should not take away is that the 1995-96 shutdowns themselves were a political disaster for Republicans. Certainly, the government shutdown didn’t help the GOP’s image, but the party had lost support among the public well before the initial shutdown in November 1995. The government shut down twice between then and January 1996 (Nov. 14-19; Dec. 16-Jan. 6).

First, some political history. A year earlier, the GOP scored a sweeping victory in the 1994 midterm, winning both the House and Senate for the first time in 42 years. The public set a high bar – perhaps too high, in retrospect – for GOP achievements. A Pew Research Center report in December 1994 characterized post-election reactions this way: “Public Expects GOP Miracles.”

No miracles were forthcoming. The GOP’s agenda quickly got bogged down in Congress and some of its signature proposals –such as limiting the growth of Medicare spending – proved unpopular.

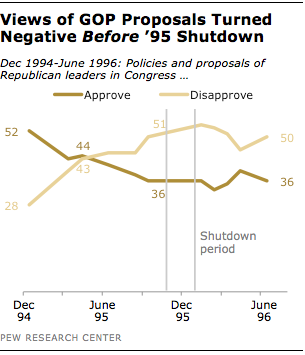

Public views of Republican leaders’ policies, which were nearly two-to-one positive in the month after the election (52% approve, 28% disapprove), turned negative just eight months later. In August 1995, 38% approved GOP leaders’ proposals while 45% disapproved. Notably, these opinions did not change much over the following year – including through the period of the two government shutdowns.

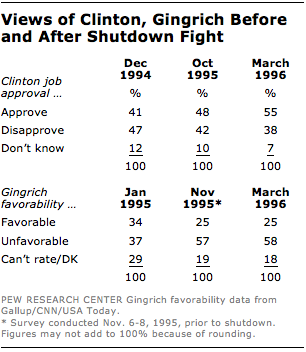

House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s favorable ratings also declined in the months leading up to the shutdown. Favorability ratings of Gingrich went from mixed in January 1995 to heavily negative by early November (57% had an unfavorable view of Gingrich, 25% favorable).

By contrast, Bill Clinton’s job approval rating moved in the opposite direction over roughly the same period. In December 1994, a month after the Democrats’ shellacking in the midterm, Clinton’s approval rating was in negative territory; just 41% approved of his job performance and 47% disapproved. In October 1995, shortly before the shutdown, Clinton had a positive rating (48% approve, 42% disapprove).

Clinton’s job rating continued to improve, reaching 55% by March 1996. Gingrich’s favorability remained largely unchanged (25% favorable, 58% unfavorable).

A year after the first government shutdown, Clinton went on to soundly defeat Sen. Bob Dole to win a second term in the White House. A strong economy was a bigger factor in Clinton’s victory than any other issue, according to national exit polls. Despite Clinton’s victory, Republicans maintained their majority in the House for the first time since the Great Depression and added two seats to their majority in the Senate.