Our households – who lives with us, how we are related to them and what role we play in that shared space – have a profound effect on our daily experience of the world. A new Pew Research Center analysis of data from 130 countries and territories reveals that the size and composition of households often vary by religious affiliation.

Our households – who lives with us, how we are related to them and what role we play in that shared space – have a profound effect on our daily experience of the world. A new Pew Research Center analysis of data from 130 countries and territories reveals that the size and composition of households often vary by religious affiliation.

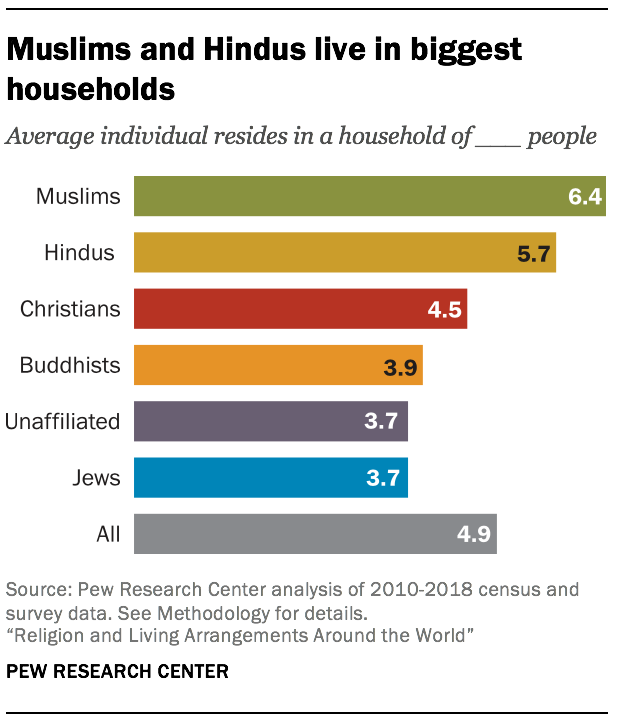

Worldwide, Muslims live in the biggest households, with the average Muslim individual residing in a home of 6.4 people, followed by Hindus at 5.7. Christians fall in the middle (4.5), forming relatively large families in sub-Saharan Africa and smaller ones in Europe. Buddhists (3.9), Jews (3.7) and the religiously unaffiliated (3.7) – defined as those who do not identify with an organized religion, also known as “nones” – live in smaller households, on average.

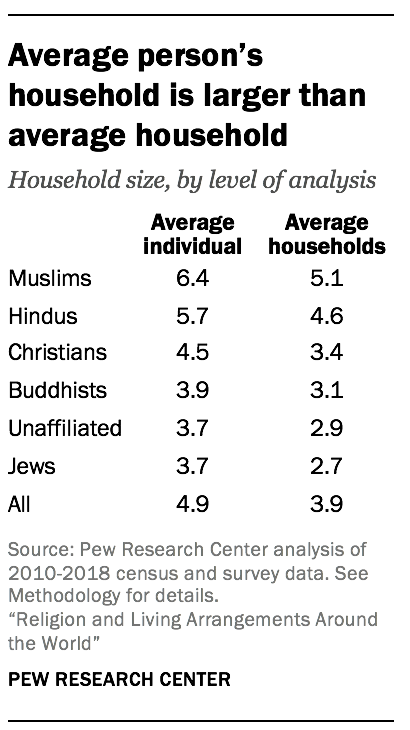

This report looks at households from the perspective of an average person, rather than an average household. While it is possible to calculate statistics either way, researchers chose the individual perspective because it better captures the lived experience of most people. Consider two homes, one with a family of nine people, the other with a sole resident. The two households contain a total of 10 people, so the average household size is five. But most of the individuals in these two homes – nine out of 10 – live with more than five people. In fact, in this simple example, the average individual resides in a household of 8.2 people. (Here’s the math: Nine individuals, each living among nine people, plus one household of one person, is 9+9+9+9+9+9+9+9+9+1 = 82 /10 people total = an average person residing in a household of 8.2 people.) For more on this topic, see this sidebar.

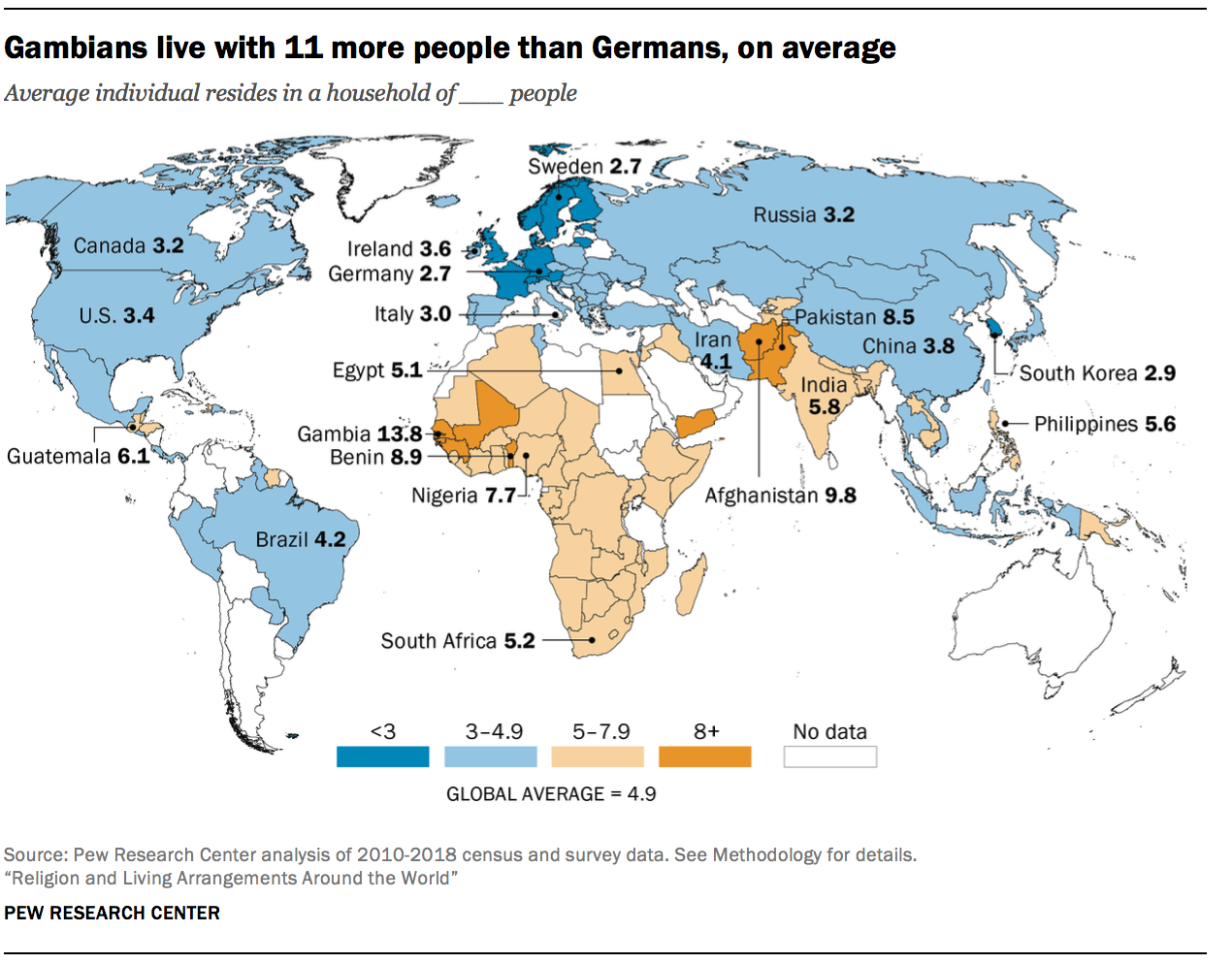

Household size is one easy way to compare the lived experiences of people around the world. Bigger households are common in less-developed countries, where people tend to have more children and families share limited resources. Smaller households are prevalent in wealthier countries, which tend to have aging populations and lower birth rates.

Household types defined

But the number of people in any given household is only one dimension of living arrangements. Since households of the same size can be so qualitatively different from each other – a three-person household might consist of a couple and one child, a child with a parent and grandparent, a husband and two wives, or numerous other combinations – understanding the distribution of various types of households also is valuable.

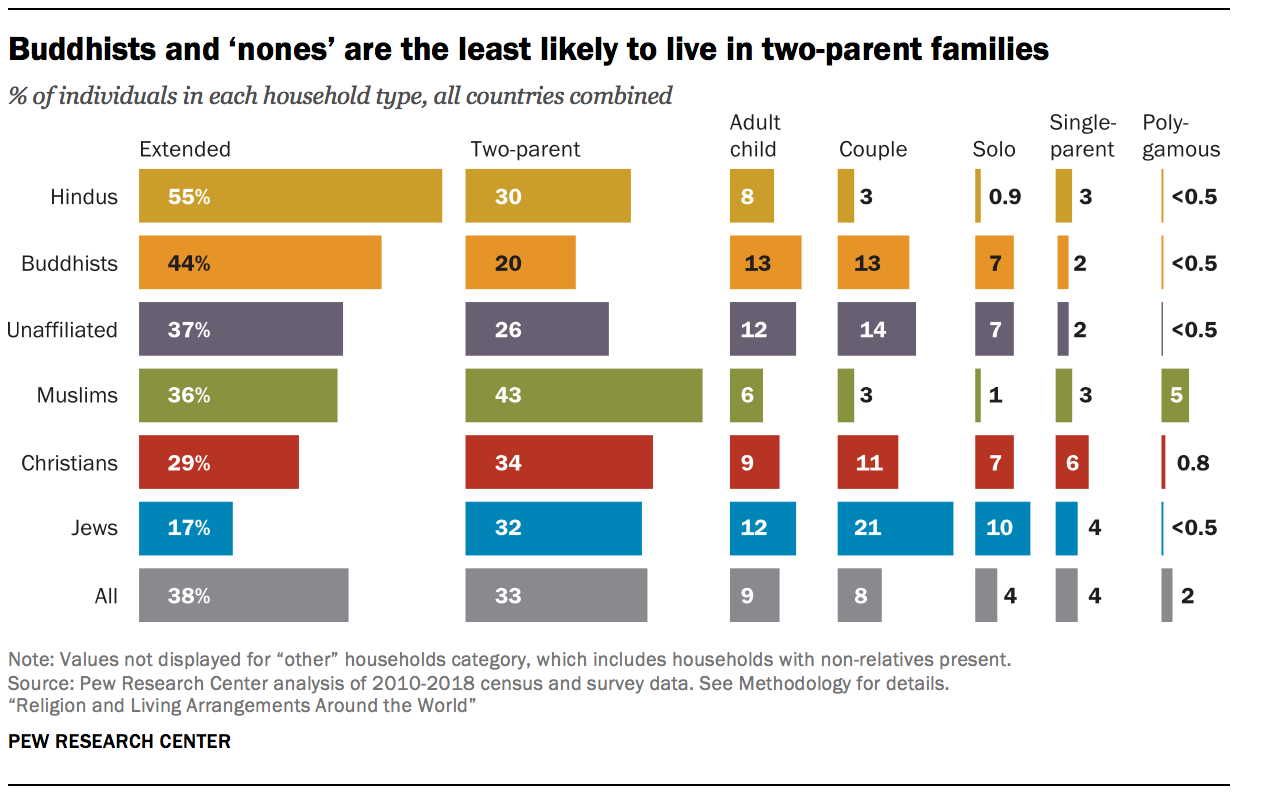

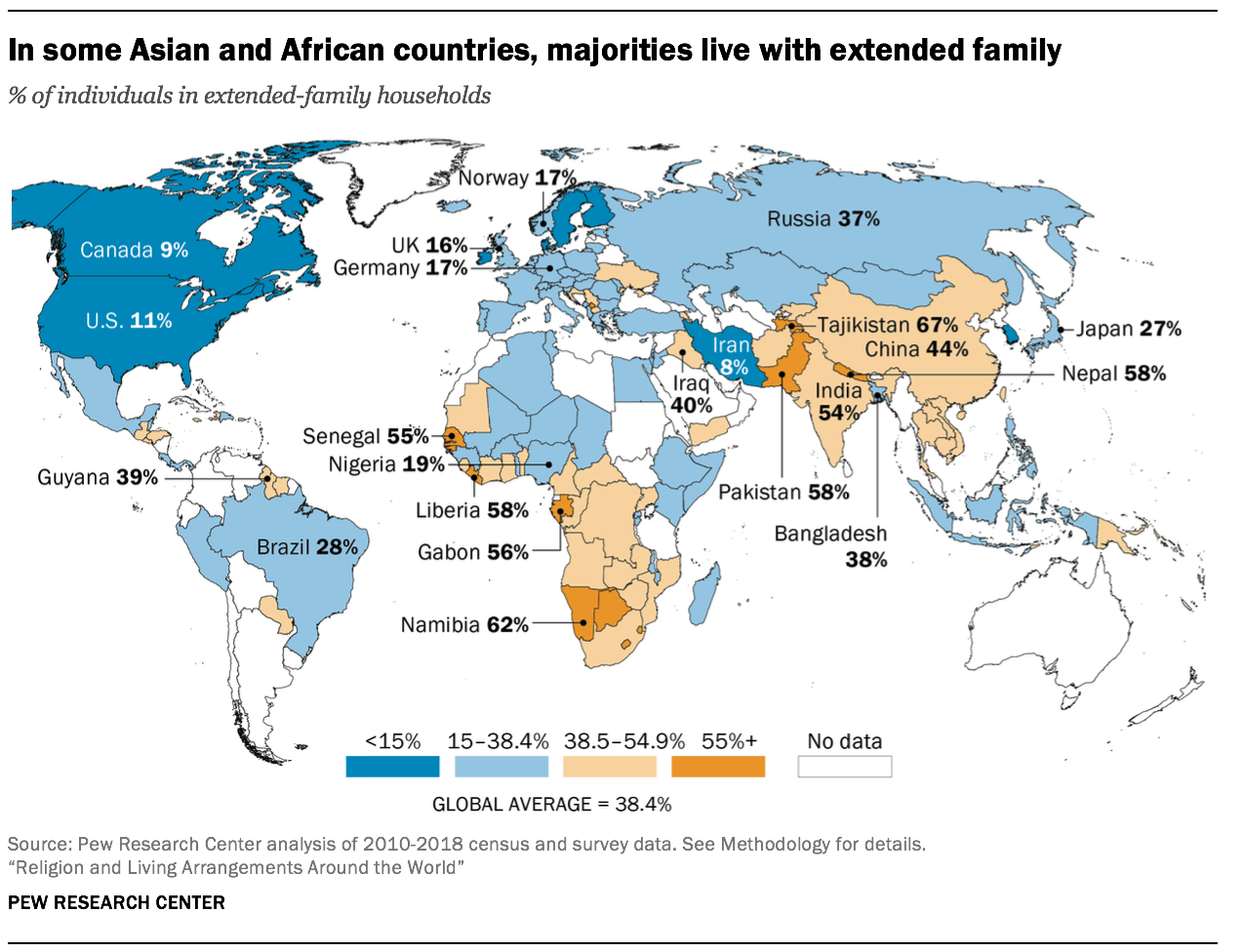

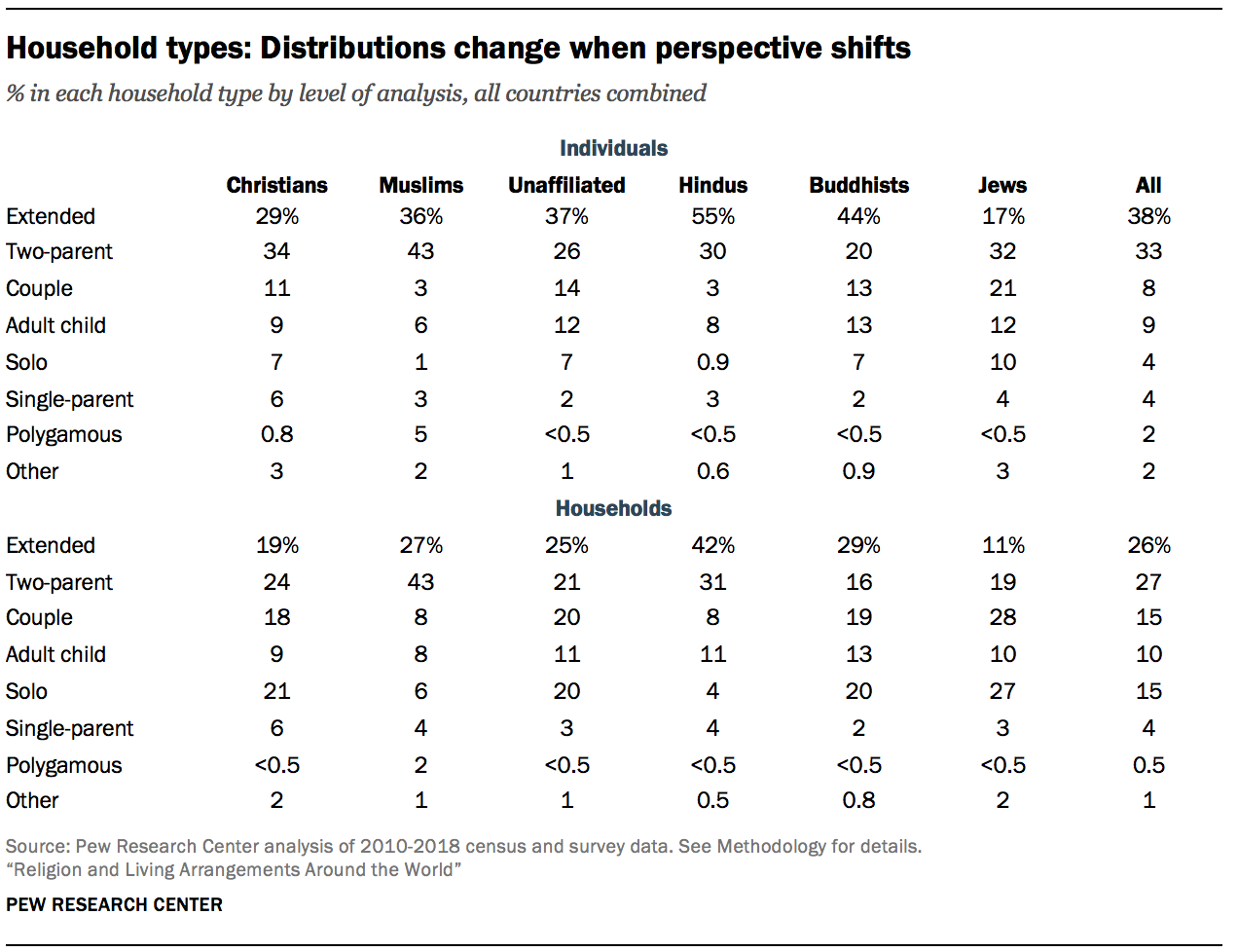

Globally, the most common household type is the extended family, accounting for 38% of the world’s population. But some religious groups are more likely to live in extended families than others. Hindus are the only major group in which a majority lives with extended family, such as grandparents, uncles and in-laws. Muslims, Christians and Jews are more likely to reside in two-parent households, composed of two partners with one or more minor children. Living alone is unusual among all religious groups, but it is more common among Jews than among the world’s other major religions: About one-in-ten Jews worldwide are in solo households. From a global perspective, Jews also are much more likely than non-Jews to live in households consisting of a couple without children or other relatives.1

How or why religion is linked with living arrangements has been the subject of much research and debate. Holy texts and spiritual leaders offer a range of guidance – from didactic anecdotes to outright prohibitions – on many aspects of family life, including marriage and care for elders. Previous social science research, particularly in the United States, suggests that the extent to which people value religion and participate in a religious community is tied to their patterns of marriage, divorce and childbearing. (For a discussion of how religious teachings and family life may be connected, see this sidebar. For more on academic research exploring the ties between living arrangements and religion, see this sidebar in Chapter 2.)

To be sure, religion is far from the only factor – or even the primary factor– affecting household sizes and types around the world. People’s living arrangements are shaped by many circumstances, including laws, cultural norms, personal situations and economic opportunities. Still, examining the connections between households and religion helps to illuminate the conditions under which members of various religious groups grow up, practice their faith and pass on traditions to the next generation.

To be sure, religion is far from the only factor – or even the primary factor– affecting household sizes and types around the world. People’s living arrangements are shaped by many circumstances, including laws, cultural norms, personal situations and economic opportunities. Still, examining the connections between households and religion helps to illuminate the conditions under which members of various religious groups grow up, practice their faith and pass on traditions to the next generation.

Geography and other factors affect household formation

Some household patterns can be explained, at least in part, by the distribution of religious groups across the globe. Six-in-ten Christians live in the Americas and Europe, where households tend to be comparatively small, while eight-in-ten Muslims live in the Asia-Pacific and Middle East-North Africa regions, where households generally contain more individuals. Most of the world’s Jews live in the United States and Israel – two economically developed countries where advanced transportation and health care networks, educational opportunities, and other forms of infrastructure affect many life choices, including living arrangements.

At the same time, there are relatively few religiously unaffiliated people in the regions where families are largest – sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East-North Africa. Moreover, because some religious groups are concentrated in a few countries, the economic conditions and government policies in those places can have a big influence on a group’s global household patterns.

China, for example, is home to a majority of the world’s “nones” and about half of all Buddhists. From 1979 to 2016, the Chinese government enforced a “one-child policy” that penalized couples who had more than one child.2 As a result, the size of households among Chinese Buddhists and “nones” is small – and China’s huge population has a big influence on the global figures for these groups. Meanwhile, more than nine-in-ten of the world’s Hindus are found in India, where prevailing cultural norms shape many of the findings for that religious group.

Nigeria exemplifies the complexity and interconnectedness of factors that influence living arrangements. Africa’s most populous country is nearly evenly split between two religious groups, with Muslims and Christians each accounting for about half of the population. These groups have different historical legacies, laws and geographic distributions. Largely due to the influence of Christian missionaries, who entered Nigeria via the Atlantic coastline to the south, most Nigerians in the southern states are Christian, while those living in the north tend to be Muslim. Sections of Africa that were reached by missionaries often have more advanced systems of formal schooling today, while aid and research agencies have found that in Nigeria, the northern states have lower rates of educational attainment and economic development.3

These differences extend to household formation. Typically, Muslims in Nigeria share their homes with almost three more people than their Christian compatriots, with an average household of 8.7 people among Nigerian Muslims, compared with 5.9 among Nigerian Christians. Also, although there is no national law providing for polygamy in Nigeria, polygamous marriages are recognized in 12 northern, Muslim-majority states – and Nigerian Muslims are much more likely than Christians to live in polygamous households (40% vs. 8%). (For a detailed discussion of polygamy in laws and religion, see here.)

In broad strokes, these examples show why it is difficult to isolate the causal impact of religion, which is inextricably linked to economic, geographic, legal and cultural factors not only in Nigeria but around the globe. Each country and part of the world has its own complex set of influences that affect household formation, resulting in a varied landscape of living arrangements.

Among the 130 countries with data available on households and religious affiliation, the household size experienced by the average person ranges from 2.7 people (in Germany) to 13.8 people (in Gambia). By region, people tend to form the smallest households in Europe (3.1) and North America (3.3). The biggest households are in sub-Saharan Africa (6.9) and the Middle East-North Africa (6.2). Latin America and the Caribbean (4.6) and the Asia-Pacific region (5.0) fall in the middle.

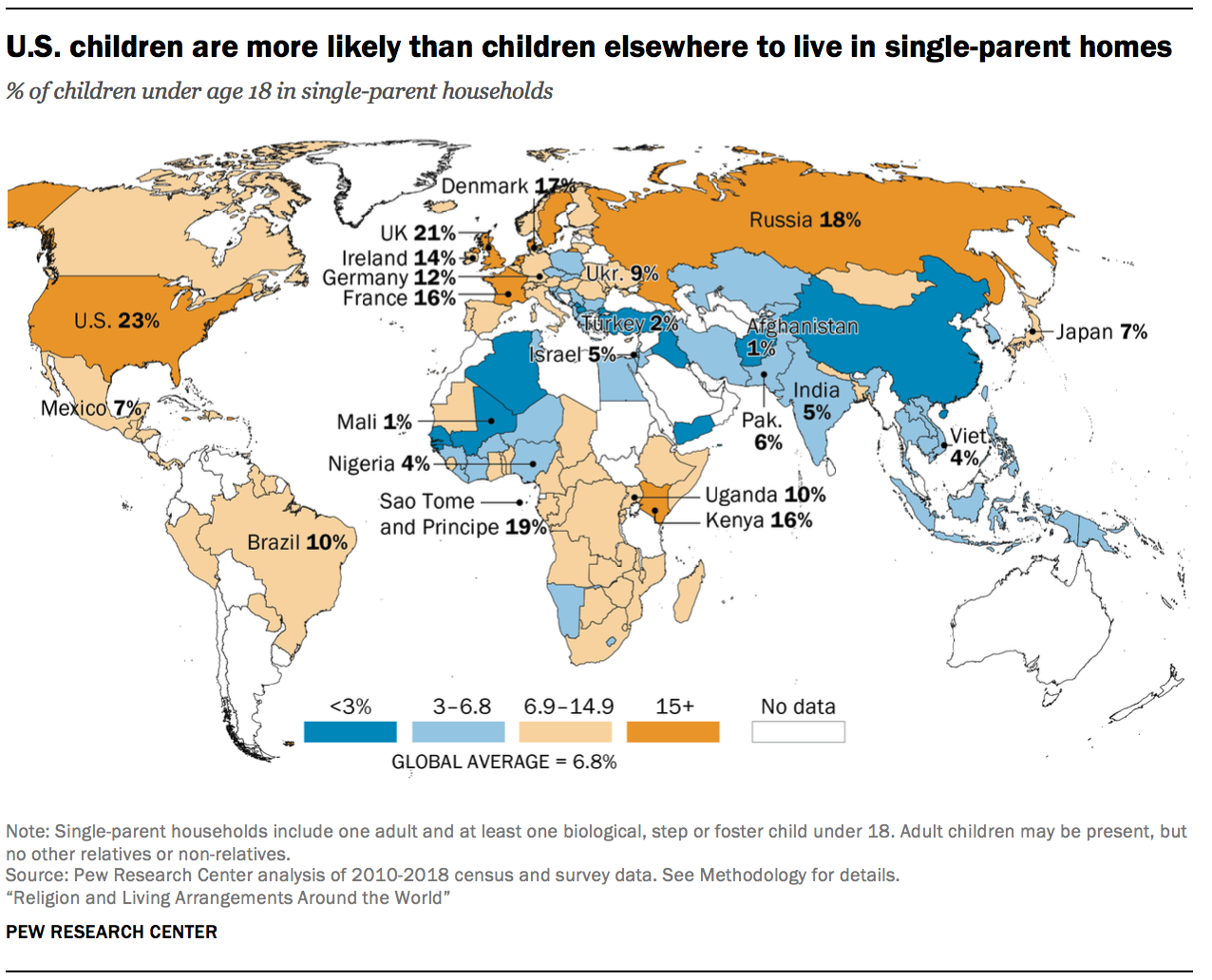

Likewise, certain types of households are more prevalent in some parts of the world than in others. For example, almost half of all people in the Asia-Pacific region live with extended family, compared with just one-in-ten North Americans. Polygamous households are rare outside of West Africa, where the practice is quite common in some countries.4 And couples rarely live on their own – without children or extended family – outside of Europe and North America.

Regional patterns, in turn, influence the living arrangements among religious groups. Muslims in Europe, for example, generally live in larger households than non-Muslims in Europe (4.1 vs. 3.1, on average). Still, European Muslims follow the region’s overall tendency toward relatively small households, and Muslims in Europe live with fewer people than Muslims in other parts of the world.

Measuring households from the individual’s perspective – why does it matter?

To gain a better understanding of how the individual-level figures in this report might differ from the more conventional household-level analysis, our researchers also generated results for all the variables on the household level, whenever possible. The tables in this sidebar summarize the differences.5

Wealth and education: Smaller homes in more-developed countries

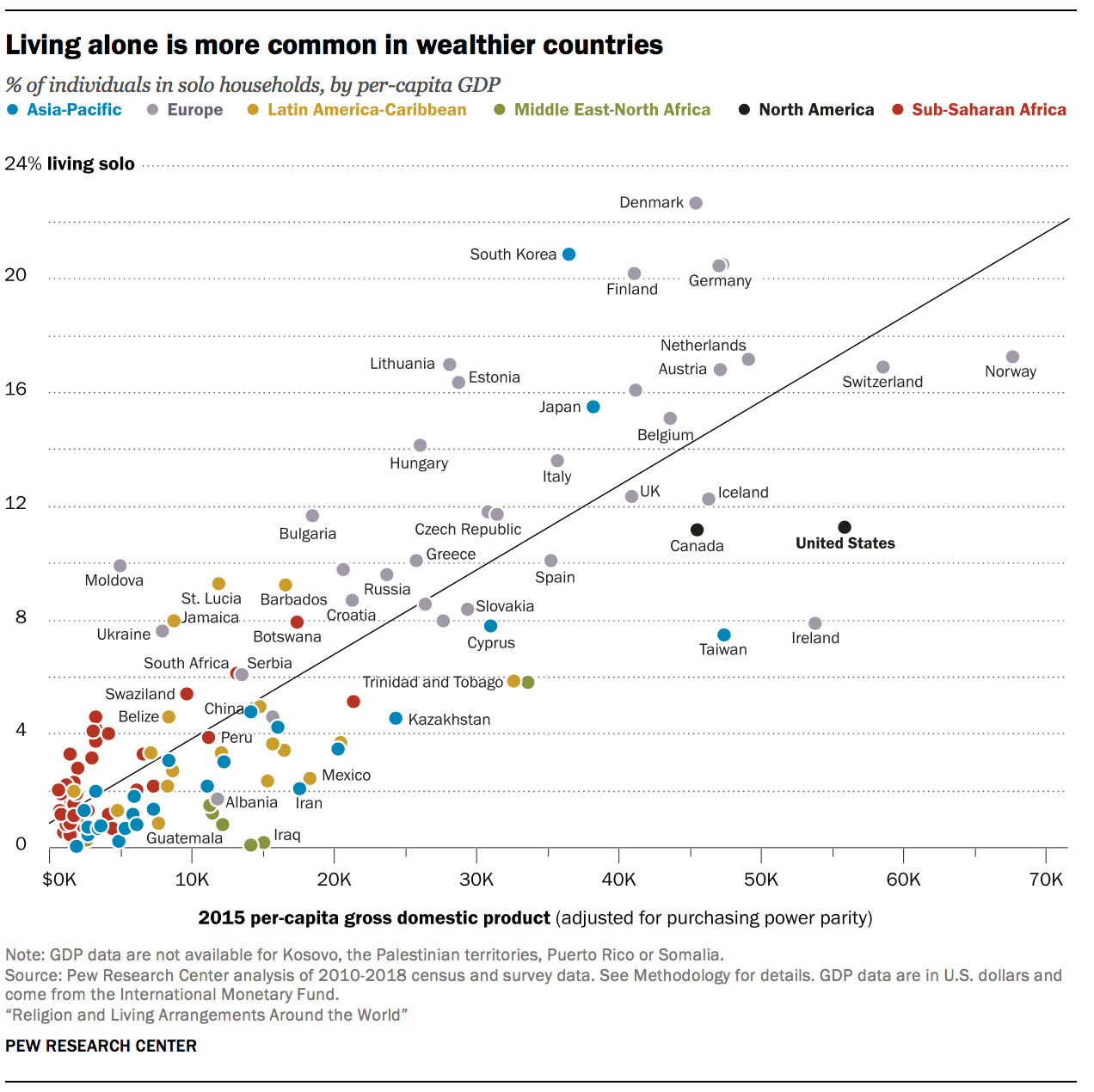

Levels of prosperity – defined by a range of measures including financial stability, life expectancy and education – are strongly linked with the size and type of households around the world. Europe and North America, the two wealthiest regions as measured by per-capita gross domestic product, are also those with the smallest households. Conversely, sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East-North Africa region, which have the biggest households, have the lowest per-capita GDP.6

Extended-family arrangements in particular are linked with economic development: Financial and other resources stretch farther when shared within one household. Childcare and domestic chores are more easily accomplished if split among several adults living in the same home. Supporting a family in developing countries is often labor-intensive, requiring farming and other activities that benefit from multiple workers. And in countries where governments provide fewer retirement benefits or other safety nets for older adults, families have a greater responsibility to care for aging relatives. (Cultural factors, such as esteem for elders, also play a role.)

On the other hand, people are more likely to live alone in countries with higher levels of schooling. Young adults often delay or forgo childbearing to pursue advanced education, contributing to the tendency of highly educated couples to live without other family members. And in places where people tend to live well beyond their childbearing years, they are more likely to live alone as seniors or as couples without children.

Economic development also affects patterns within regions. In Europe, relatively small households predominate in prosperous European Union countries (the average German or Swede lives in a home of 2.7 people, for example), while larger households are found in the less economically advanced countries of the Balkans (Kosovo 6.8, North Macedonia 4.6). In East Asian countries with advanced economies, people tend to live in smaller-than-average households (South Korea 2.9, Japan 3.1), while residents of less-developed countries in South Asia tend to have bigger households (Afghanistan 9.8, Pakistan 8.5).

Although the regional distribution of religious groups often coincides with economic factors that affect the types and sizes of households people tend to live in, there are noticeable differences among religious groups within the six regions covered in this report, and even within single countries.7

Indeed, this report shows that the experiences of religious groups around the world differ in many ways:

- Islam is the largest religion in all but one of the 15 countries with the biggest households: Benin. These top 15 include nations in Africa, such as Gambia and Senegal; the Middle East, namely Yemen and Iraq; and the Asia-Pacific region, including Afghanistan and Pakistan. On the other hand, Christians and the religiously unaffiliated make up the largest groups in the 15 countries with the world’s smallest households (all of which are located either in Europe or the Asia-Pacific region).

- Within regions, Muslim-majority countries tend to have larger households, affecting members of all religious groups, while nearby Christian-, Jewish- or Buddhist-majority countries tend to have smaller households. For example, in Kosovo, which has a Muslim majority, both Christians and Muslims tend to live in bigger households than adherents of these religions in nearby Romania, which has a Christian majority.

- Within countries, religious groups often differ in their living arrangements. In Senegal, for example, Muslims on average live in 14-person households, while Christians live in homes of about nine members. In Nigeria, a nine-member household is the average Muslim’s experience, while the average Christian lives in a six-person home. And in India, Muslims live in the largest households, with an average size of more than six people, compared with slightly fewer than six people for Hindus, on average. Christians in India have even smaller households, with an average of about five members.

- Relatively few people in any group live alone (4% globally), though Jews (10%), Buddhists (7%), Christians (7%) and “nones” (7%) all live alone at higher rates. Muslims and Hindus rarely form solo households (1% each).

- Similarly, Muslims and Hindus are the least likely to live as couples (without children or other relatives), with just 3% in each group living in such an arrangement. By contrast, at least one-in-ten Christians, Buddhists and “nones” live this way, as do one-in-five Jews.

- Polygamy is very rare, except in some sub-Saharan African countries where this type of marriage is largely legal. While African Muslims are more likely than Christians to live in polygamous households (25% vs. 3%), the practice is also widespread among adherents of folk religions (who are not analyzed separately in this report) and “nones” in certain countries.

- In the U.S., Christians (3.4), “nones” (3.2) and Jews (3.0) live in similarly sized households, on average. However, U.S. Jews are much more likely than non-Jews to live as couples without children or other relatives, and they are less likely to reside in extended families and single-parent households.8

- Men in every country are older, on average, than their wives or female cohabiting partners. This age gap is widest among Muslims and Hindus, and smallest among Jews and the religiously unaffiliated.

- Women ages 60 and older are more likely than men in this age group to live alone. Three-in-ten Christian and Jewish women over 60 live alone, while only 6% of Hindus do.

- More Christians than members of any other religious group live in single-parent homes (6%). And women, particularly Christian women, are more likely than men to live as single parents. In the U.S. – the country with the world’s largest Christian population – about a quarter of children live in single-parent homes, making them more likely than children in any other country to do so. American children in Christian homes are just as likely as those in unaffiliated homes (23% each) to live in single-parent situations.

These are among the key findings of a new Pew Research Center analysis of census and survey data collected by governments and survey organizations in 130 countries since 2010. This report was produced by Pew Research Center as part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. Funding for the Global Religious Futures project comes from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation. Previous reports from the Global Religious Futures project explored links between religion and gender, education, age and personal well-being, and produced population growth projections for major religious groups.

Statistics come from Pew Research Center analysis of sources, which include Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys, Demographic and Health Surveys, census data archived by IPUMS International, General Social Surveys and European Social Surveys, as well as country-specific studies. The study covers countries where 91% of the global population lives.9 Unless otherwise specified, results describe the average living arrangements experienced by people of all ages (that is, children and adults). For more details, see Methodology.

In addition to analyzing household sizes using census and household survey data and transforming it to present the average individual’s perspective (as opposed to the average household), researchers also analyzed eight household types among the major religious groups, broken down by age and gender. The report focuses on descriptions of seven household types that are made up of individuals living alone or with family members, though about 2% of all people living in households fall into the residual eighth (“other”) category, including those who share housing with unrelated roommates or a mix of relatives and non-relatives. All statistics in this report exclude institutionalized populations, such as people in prisons, college dormitories and nursing homes.

The next section of this report explores how holy texts and spiritual leaders have addressed the question of household formation. Subsequent chapters outline patterns in household sizes and types by region and religious group, including a discussion of previous social science research on the connections between living arrangements and religion. The final chapter focuses on how living arrangements vary by age and between women and men.

Religious teachings on families and homes

Holy texts and spiritual leaders have much to say about domestic life. All the major world religions – including but not limited to Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism – promote specific types of family formations and offer guidance on the roles that people play within the home. These teachings take many forms, from explicit rules to popular sayings and stories.10

But teachings are not static or universal. Interpretations of religious texts vary by place and shift across time, and religious leaders in the same context often disagree. For nearly two centuries, scripture was used by some U.S. Christian clergy to justify opposition to interracial spousal relationships. But societal views and laws shifted in the 20th century, and Bible passages once viewed as censuring ties between races have largely been pushed aside.

Procreation

Bearing, raising and protecting children is a central theme in many religions. Christianity and Judaism encourage adherents to have children, and in Genesis – the first book of the Jewish Torah and the Christian Old Testament – God commanded humans to “be fruitful and multiply.” The Quran, which emphasizes the importance of motherhood and childbearing, has a handful of references to pregnancy and birth.11

Outside of the Abrahamic religions, the Hindu Vedic texts also contain passages about having children. The Marriage Hymn of the Rig Veda, which is sometimes recited at Hindu weddings, states “Let Prajapati create progeny for us,” and “Generous Indra, give this woman fine sons. … Place ten sons in her and make her husband the eleventh.”12

Buddhism is not considered to be particularly pro-natalist, which some scholars have tied to relatively low fertility rates in that religious group.13

A religion can promote having children even if it does not have specific doctrines endorsing procreation. Some scholars say that teachings of conservative Islam and Christianity indirectly lead people to have more children due to the gender roles they endorse.14 Religion also can indirectly encourage procreation through other means, such as opposition to birth control. In Judaism, a couple’s inability to have children can be grounds for divorce.

Marriage

Closely tied to childbearing, religions often set rules for marriage and sexual relations. According to Genesis 2:18, woman was created because “it is not good that the man should be alone.” In the Christian New Testament, Paul the Apostle wrote, “Because of cases of sexual immorality, each man should have his own wife and each woman her own husband.” In Islam, the Quran states that God created “love and mercy” between spouses.

In Hinduism, the ashrama system specifies four stages of the life course, including the second stage of life, grihastha, in which one becomes a householder and focuses on marriage, raising children and fulfilling obligations toward elders and other relatives.

In Buddhism, the Sigālaka Sutta offers instructions on how spouses should treat one another: “There are five ways in which a husband should minister to his wife as the western direction: by honoring her, by not disparaging her, by not being unfaithful to her, by giving authority to her, by providing her with adornments.”15

Scriptures provide a mix of guidance on interfaith marriage. In the Torah, Moses tells the Jews that they must not intermarry with those from the seven nations of Canaan, which some interpret as a prohibition on all religious intermarriage. And, according to the Talmud, a rabbinic commentary on Jewish scripture, both participants must see the marriage ceremony as sacred in order for it to be religiously valid.16 The Christian New Testament, however, is less clear on the topic of intermarriage. In his letter to the Corinthians, Paul wrote: “Do not be mismatched with unbelievers,” which is often thought to prohibit marriage to non-Christians. However, Paul also instructed believers not to divorce their unbelieving spouses.

In Islam, critics of interfaith marriage typically cite Surah 2:221: “Do not marry idolatresses until they believe: a believing slave woman is certainly better than an idolatress, even though she may please you. And do not give your women in marriage to idolaters until they believe: a believing slave is certainly better than an idolater, even though he may please you.”

Polygamy

Polygamy was practiced by central figures in Judaism, Christianity and Islam and, more recently, by early leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the 19th century. Many prominent biblical figures were polygamous, including Jacob, David and Solomon. Generally speaking, polygamy is no longer encouraged by the leaders of major religions, though it is practiced by some Muslims, fundamentalist Mormon sects and Christians in Africa. Muslim supporters of polygamy often cite Quran verse 4:3, which permits a man to marry up to four women, but encourages him to be monogamous if he cannot be fair to all of them.17 Scholars have interpreted this text as a way to regulate and limit polygamy in seventh-century Arabia, where it was widely practiced. (For more on polygamy laws and teachings, see this sidebar.)

Divorce

Religions often discourage divorce. The Christian New Testament specifies, “Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate.” Still, many religions recognize the reality that some marriages will not last. In the Old Testament, Deuteronomy states that the process of divorce is enacted when a man writes his wife a certificate.

The Quran specifies the requirements for divorce and outlines a man’s responsibilities toward his former wife. Islam allows a woman to retain any assets she earns or receives during a marriage and gives her the right to receive support from her former husband.18

According to a Confucian text, The Record of Ritual of the Elder Dai, there are seven valid reasons a husband may divorce his wife – including “if she has no children” or “if she steals” – and three situations in which a wife may not be divorced, including if “there is no longer a home to which she can return.”19

Teachings that address the status of elders and other relatives outside of the nuclear family may also encourage certain types of living arrangements, including extended families. Hinduism, which emphasizes a respect for elders, also has guidelines for responsibilities toward other relatives in the second stage of life, the grihastha ashram.20

Judaism and Christianity instruct followers to respect their elders in the Ten Commandments: “Honor your father and your mother.” And the Book of Leviticus, which is part of both Christian and Jewish scripture, states: “You shall rise before the aged, and defer to the old.” Similarly, the New Testament says: “And whoever does not provide for relatives, and especially for family members, has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever.”

Confucian texts also encourage support for aging parents and emphasize filial piety.21